The American housing market mirrors our society, the decisions we make, and the problems they leave us with, according to a report out Tuesday.

Inequality is widening as competition remains fierce for scant resources. Finding housing is getting harder for those of lesser means – and people of color – and maybe a tiny bit better for everyone else. And homeownership provides a bit of an economic edge – for those who can grab it.

Those are the takeaways from the annual report known as The State of the Nation’s Housing, produced every year by the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. The report lives up to its weighty title, with 44 pages, dozens of charts and tables, and details on everything from the cost of land to the country of origin of recent immigrants. But the report’s most important data points are the ones that remind us, once again, that the way we create housing isn’t working for many Americans.

There aren’t enough homes to go around

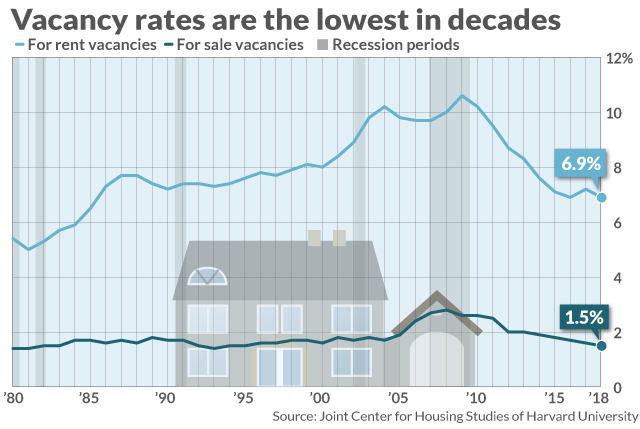

Housing is tight. In 2018, the vacancy rate for owner-occupied homes was the lowest since 1995. The vacancy rate for renters matched 2016 for the lowest since 1985. (The combined rate was 4.4%, the lowest since 1994.)

More higher-income people are renting – the Harvard researchers say there were 311,000 more tenant households earning more than $75,000 in 2018 than the year before. That’s great for developers and landlords, but not so hot for households that need lower-cost rents.

As the researchers note, “The focus of new construction on higher-cost units has thus shifted the overall distribution of rents upward.” Over just one year, 2016-2017, the supply of newly-built homes renting for less than $800 fell by 1 million. And those units aren’t being replenished. In the first quarter of 2018, the researchers say, only 9% of apartments completed had asking rents below $1,050.

Of course, there haven’t been enough homes for renters or for owners in most income segments for several years. “The duration of today’s tight conditions is unprecedented,” the researchers said. It’s not just that there’s not building enough to keep up with population and household growth: there’s not even building enough to keep up with homes becoming obsolete. The Joint Center estimates that there was a shortfall of about 260,000 units in 2018, and that construction has barely kept pace with household growth for eight years. That tracks with other estimates of a housing shortfall in the millions.

The rent hasn’t gotten any damn cheaper

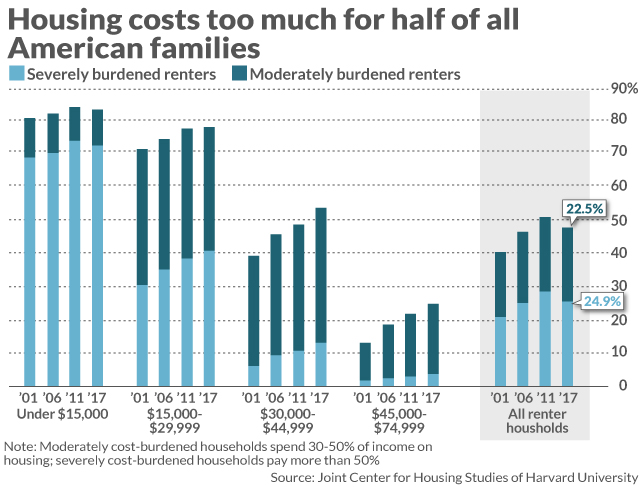

With those conditions in mind, it’s no wonder that more American renters are “cost-burdened.” As the chart below shows, one-fifth of households that rent are paying between 30% and 50% of their income on housing costs, while one-quarter are paying more than 50%.

But the burden is falling disproportionately on the poor: nearly three-quarters of renters with incomes of $15,000 or less are spending more than half their income on housing.

There are consequences for high rents

When rent is too high, it keeps younger people from becoming independent. Only 31% of 25-29-year-olds in the highest-cost metro areas formed their own households, compared to 41% in the lowest-cost areas.

It also leaves less money for other essentials. Severely cost-burdened renters were able to spend about one-fourth of the amount of non-burdened renters on health care, according to Joint Center estimates. Unburdened renters spent nearly three times as much on transportation, which also signals access to jobs.

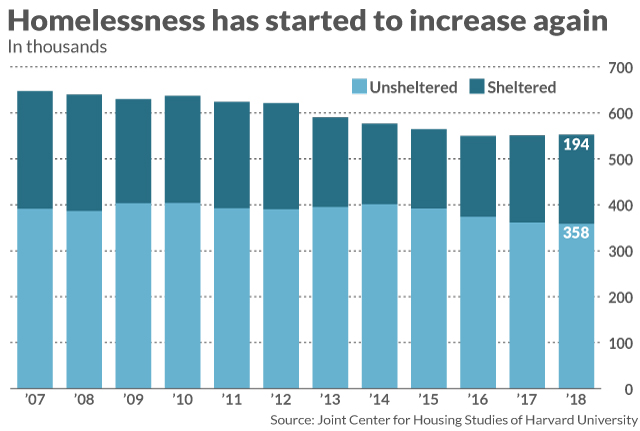

Even worse, after a multi-year decline, homelessness rose in 2018 for the second year in a row. And the number of “unsheltered” homeless was up for the third straight year.

Homeowners have it made?

Homeowners have it a little easier than renters, the Harvard researchers conclude, at least in one sense. The share of owners who are cost-burdened keeps falling, and in 2018 hit its lowest level of the century. Also, the amount of equity Americans hold in their homes just keeps rising, along with home prices, providing nest eggs for children’s higher education, small business formation, retirement, and more.

That’s nice work if you can get it, but not everyone can. More areas of the country are increasingly unaffordable. Higher-cost homes mean bigger down payments must be saved – no easy feat when rents are so expensive – or a greater debt burden for those who choose to make small down payments.

Getting a mortgage and closing on a home remains a slog, although credit conditions have eased slightly from the post-crisis period. Some 68% of renters thought that it would be somewhat or very difficult to obtain a mortgage last year, the researchers report. Among those who closed on a home in 2016, “significant numbers of respondents reported issues with the closing process. Fully 15% said that they faced an “unpleasant surprise” such as having the closing rescheduled, needing more cash than expected, having mortgage terms change, or being asked to sign blank documents.”

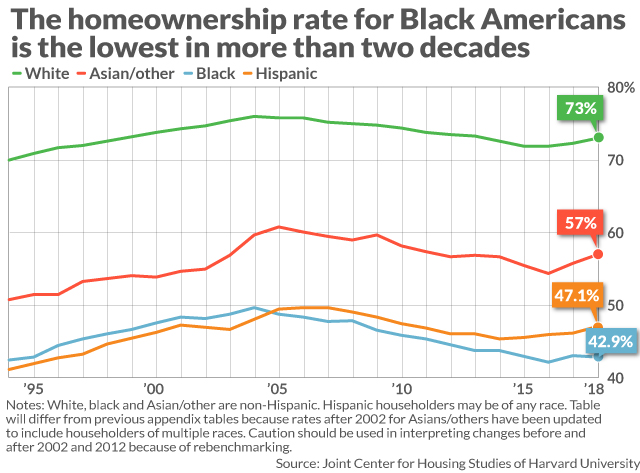

That’s an observation that’s uncomfortably reminiscent of the naughtiness that helped precipitate the housing crisis in the first place. One group of Americans probably doesn’t need that reminder. After taking a small step forward in 2017, the black homeownership rate fell again in 2018, and now stands at the lowest since 1995. Every other ethnic group gained in the past year.

— Terrence Horan contributed to this story