Child sex trafficking is far more common than many people realize, experts say — but there are plenty of ways to help the victims.

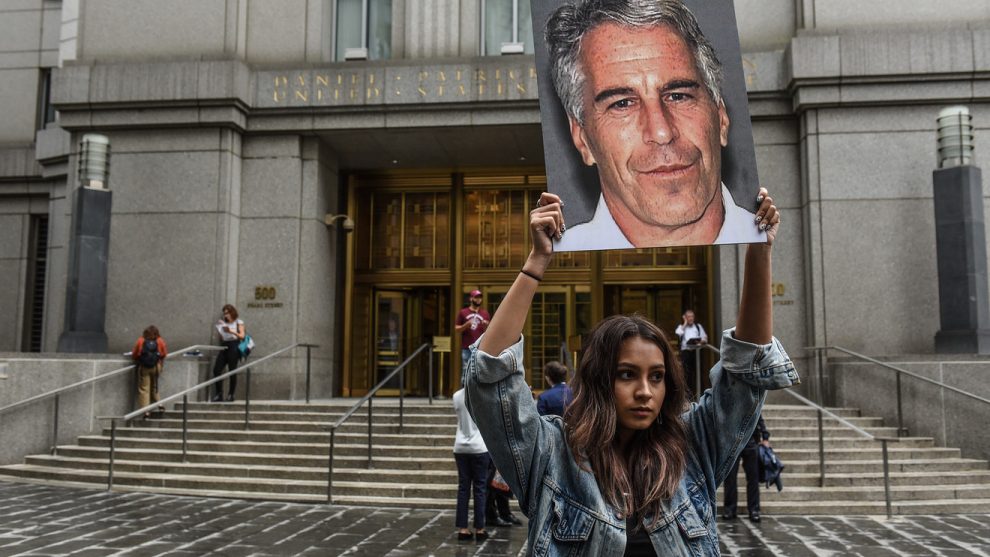

Well-connected financier Jeffrey Epstein’s recent federal indictment served as the latest prominent case: Prosecutors on Saturday charged Epstein, 66, with operating a sex-trafficking ring, alleging he had sexually abused and exploited dozens of underage girls in exchange for money from 2002 to 2005.

He lured victims in New York and Palm Beach into massages that graduated to sexual abuse, prosecutors said, paying some victims to recruit additional girls for abuse. Another woman told NBC News on Wednesday that Epstein had raped her when she was 15, following a year of massages she gave him while he pleasured himself.

‘All the adults in these children’s lives didn’t pay attention and didn’t do anything about it.’

Epstein pleaded not guilty Monday to the new charges.

The indictment and new allegation came more than a decade after Epstein cut a much-criticized “sweetheart” plea deal in 2008 with then-U.S. Attorney Alex Acosta, who would go on to serve as President Trump’s labor secretary, after police and prosecutors in Florida alleged he had sexually abused dozens of underage girls.

Acosta defended his handling of the matter Wednesday; by Friday, he had resigned.

Epstein’s famous friends have moved to distance themselves from him: Trump, who in 2002 called the hedge-fund manager “terrific” and noted he liked women “on the younger side,” said this week they’d had a “falling out” and hadn’t spoken in 15 years. Bill Clinton, who had flown on Epstein’s plane, said in a statement this week that he “knows nothing about [Epstein’s alleged] terrible crimes” and hadn’t spoken to him in more than a decade.

But Marci Hamilton, a child sex-abuse expert and founder of the nonprofit think tank CHILD USA, alleges that there’s “no question” that the men who palled around with Epstein must have noticed the alleged presence of underage girls. “There’s also no question that they had to have known that these girls were supposedly providing massages — and that should have been warning bells all over the place,” Hamilton added.

There were many ways in which adults could have helped protect Epstein’s alleged victims, Hamilton said. She likened their alleged negligence to that displayed in the Catholic Church sex-abuse scandal, team doctor Larry Nassar’s serial molestation of USA Gymnastics athletes, and Penn State assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky’s years-long sexual abuse of boys.

“What is identical,” Hamilton said, “is all the adults in these children’s lives didn’t pay attention and didn’t do anything about it.”

How you can help

There are a variety of things bystanders can do to help victims of child sex trafficking, experts say, whether it’s intervening in the moment, lobbying to change laws or supporting advocacy work:

Know how to identify red flags. Take notice if a child is not attending school; is accompanied by a domineering, controlling adult who doesn’t look like a parent or guardian; has bruises; or won’t communicate with you, Hamilton said — “a child who only looks down and is clearly under the control of some outside force.”

A parent might notice their child coming home with expensive gifts despite not having a job, experiencing a sharp drop in grades, or having access to drugs and alcohol.

A parent might notice their child coming home with expensive gifts despite not having a job, experiencing a sharp drop in grades, or having access to drugs and alcohol, added Donna Hughes, a human-trafficking researcher and University of Rhode Island professor.

Other signs could include multiple instances of running away or going missing for multiple nights, said Eliza Reock, the strategic advisor for child sex trafficking at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. A child being in the possession of hotel keys, prepaid or multiple cell phones, or large amounts of cash should also raise concerns. The child may have a tattoo symbolizing ownership or money, she added. (For a comprehensive list, see NCMEC’s list of red flags.)

Common venues include truck stops, hotels and motels, and illicit massage businesses. Children can also be recruited on social-media platforms, Reock said. “If the girl responds, they start building a relationship [and] start asking to meet somewhere,” she said.

Exercise caution in approaching the child. If you’re talking to a child you know, “make sure it’s not coming across as ‘You’re in trouble’ but ‘I’m here to help,’” Reock said. “Nothing that’s blaming the child for the behavior — as opposed to ‘Why did you run?’ [say], ‘I’m so glad you’re back. What made you want to run and how can we prevent that again? How did you take care of yourself, how did you pay for that, how did you stay safe?’”

But if you suspect a child you see out in public (say, on the train) is being victimized, engaging them could endanger their safety. “I would highly recommend to not intervene,” Reock said. “Usually if it’s a pimp-controlled or trafficker-controlled situation, then that child is being watched.”

Err on the side of calling it in. If you sense imminent danger to the child, always call 911, Hamilton said. But if you believe you’re observing a suspicious pattern — like lots of kids going into the house next door to you, but never seeming to go to school — you can contact law enforcement or reach the confidential and 24/7 National Human Trafficking Hotline by calling 1-888-373-7888, texting 233733 or submitting a tip online. NCMEC also has a hotline (1-800-THE-LOST) and a cyber tip line.

“If you see a 14-year-old at a truck stop getting into a truck with a person they don’t seem to be related to … yeah, you might be wrong, but what if you’re right?” Reock said. NCMEC may already be tracking that truck’s license-plate number, she pointed out, or it may have identified that rest-stop area as a hub for human trafficking.

Provide a detailed tip. “The hotline is not there at the scene, so we’re dependent on the person to describe indicators,” said Brad Myles, the CEO of Polaris, an anti-trafficking nonprofit that operates the National Human Trafficking Hotline. Calling in with a vague suspicion doesn’t give hotline workers much to go on, so try to provide concrete, specific information, he said — any violence or threats you’ve witnessed, for example, or an online ad depicting a young-looking girl.

Support organizations that help trafficking victims. You can volunteer, donate money or offer other professional services, Myles said. (Here’s a list of anti-trafficking organizations.)

Lobby for change. Public advocacy helps, Myles said. More than 1,000 children are arrested every year for prostitution, according to 2010 Bureau of Justice Statistics data. Several states have passed “safe harbor” laws that protect victims of child sex trafficking, but it’s still permissible in many other states to charge a minor with prostitution, Myles said.

“For so long … we’ve been just trying to prove that these kids are victims and not [criminals],” Reock said. “We’re finally as a field starting to recognize that just because money has changed hands, that doesn’t change the fact that this is sexual abuse of a child.”

Several states have passed ‘safe harbor’ laws that protect victims of child sex trafficking, but other states allow a minor to be charged with prostitution.

You can also make an impact where you live, Hughes said. If you believe there are individuals in your community purchasing sex from minors, raise your concern with local organizations, police and government officials and ask them to crack down on the problem, she said.

“The best way to help girls is to get the perpetrators off the street, whether they be the sex buyers or the pimps or traffickers,” she said.

Myles also called for increased law enforcement and criminal penalties for individuals who buy sex from trafficked children. “Those buyers are participating in that child’s rapes, and they are directly participating in that child’s exploitation,” he said. “And right now, our country is nowhere where it needs to be in how frequently men are being arrested; how often men are facing real jail time.”

Be aware of missing children in your own area. Before Reock attends a training or presentation, she opens the ‘Advanced search’ on her organization’s website, MissingKids.org. She inputs the local geographic area and the age range 11 to 18, then says something along the lines of, “These are the kids that traffickers target — if you see them, report it to law enforcement, our hotline 1-800-THE-LOST or at CyberTipline.org.”

Step up. Society often fails to understand how “radically vulnerable” children are, Hamilton said, despite how adult they may dress or act sometimes. “If there’s any way to help a child who is being exploited or abused, we all need to step up more than we are now,” she said. “That’s going to mean being more proactive and essentially interfering where we might not have interfered before.”

The scope of the problem

While there’s no reliable count of child sex-trafficking victims in the U.S., the number is likely “in the hundreds of thousands” after adding up runaways and homeless youths being sexually exploited, children targeted in the foster-care and child-welfare systems, and intrafamilial pimping, Myles said.

Around one in seven endangered runaways reported missing to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) last year were likely child sex-trafficking victims, according to the nonprofit — an estimate that Reock called “incredibly conservative.”

Around one in seven endangered runaways reported missing to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children last year were likely child sex-trafficking victims.

Victims of sex trafficking are not always girls, Hamilton said. In fact, nearly six in 10 globally are women, while two-thirds of child victims are girls and one-third are boys.

Many come from disadvantaged backgrounds: One 2015 Congressional Research Service report found that “commercial sexual exploitation of children appears to be fueled by a variety of individual (e.g., homelessness or history of child abuse), relationship (e.g., family conflict or dysfunction), community (e.g., peer pressure or gang involvement), and societal (e.g., sexualization of children) variables,” though the authors noted that those factors didn’t necessarily put a child at risk.

Children subjected to sexual exploitation or sex abuse are at greater risk for depression, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder, sexually transmitted infections, illnesses and failure to achieve their potential, Hamilton said — all of which come at a cost to society.

And you’ll find child sex trafficking “in almost any community of any size,” said Hughes, particularly where any legal or illegal sex-industry businesses operate. (Think prostitution, strip clubs, private rooms in adult bookstores and illicit massage parlors.) “Anywhere you have adult prostitution, you also have children being sexually exploited,” Hughes said.

Buyers of commercial sex frequently don’t ask for a child’s age, added Myles, even as they participate in statutory rape. “They’re essentially turning a blind eye to the fact that they’re having sex with a child, or letting themselves be deceived that she’s probably 18 — but in their gut [they know] she’s probably not.”

How Epstein’s case isn’t (and is) the norm

Epstein’s case is atypical in that he wasn’t operating a criminal organization solely dedicated to child sex trafficking, Hamilton said — rather, he allegedly engaged in “legitimate business activities, along with his political activities, along with this side business of buying sex from children who were incapable of protecting themselves.”

His wealth and apparent clout with Justice Department officials are also an anomaly, Hughes said.

But on the question of how Epstein’s gender, money and privilege apparently helped him evade prosecution, Hamilton said, his example is “not that unusual.” “Whether it was Hollywood or it was powerful men in business or it was bishops, it was just commonplace that they wouldn’t prosecute if there was someone powerful in the picture,” she said. “The men would protect the men; the men would defer to the men.”