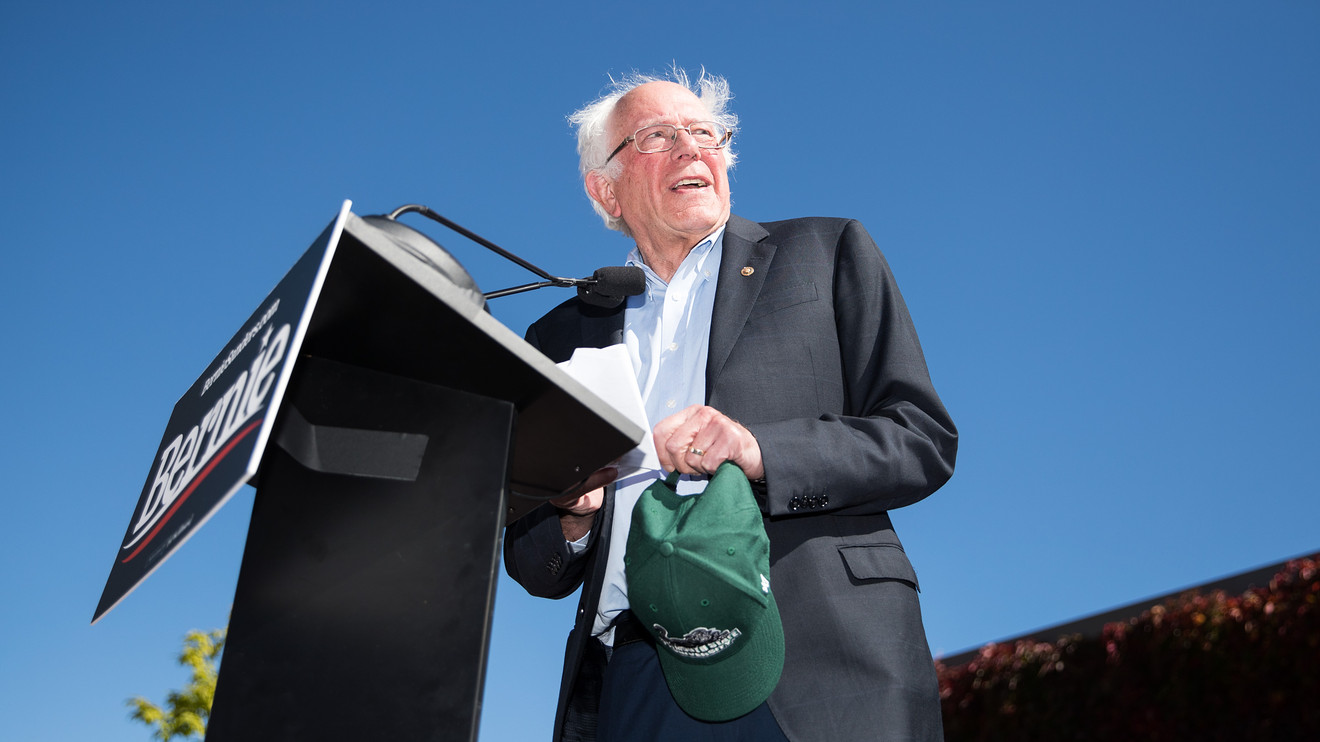

Sen. Bernie Sanders’ belated disclosure of his recent heart attack served as the latest instance of a public figure grappling with whether — and how — to talk about a serious health problem on the job.

The 2020 presidential candidate canceled his events last week after being hospitalized for chest discomfort; his campaign said days later that it was actually a heart attack.

The recuperating senator plans to participate in next week’s Democratic debate, as his supporters reportedly urge him to dial back the campaigning and speak candidly about his health, according to the Washington Post.

‘I want people to pay attention to their symptoms: When you’re hurting, when you’re fatigued, when you have pain in your chest, listen to it.

The 78-year-old Vermont lawmaker told reporters on Tuesday that he had been “dumb” to disregard the fatigue he had felt over the past month or two. “I should have listened to those symptoms,” he said. “I want people to pay attention to their symptoms: When you’re hurting, when you’re fatigued, when you have pain in your chest, listen to it.”

Sanders, whose hospitalization spurred discussion about his age and overall health, was the latest politician or celebrity to navigate the disclosure of a health condition or diagnosis: TV personality Jonathan Van Ness, for example, last month revealed he had been diagnosed with HIV years earlier, calling himself a proud “member of the beautiful HIV-positive community” who now feels the need to talk openly about his status.

And “Jeopardy” host Alex Trebek, who disclosed his Stage 4 pancreatic cancer diagnosis in March and said he was in remission two months later, has publicly endured setbacks in his cancer treatment and mused about his own mortality. He told CTV last week that his chemotherapy had taken a tangible physical toll — suggesting it could one day keep him from hosting the quiz show — and said he sometimes regretted revealing his illness.

“There’s a little too much Alex Trebek out there,” he said.

While experts stress that every person’s situation is different, here are some general tips to help guide how you discuss and manage health issues in the workplace:

Decide whether to disclose your condition to coworkers. This depends on a variety of factors, including your job, your personal communication style, whether the condition impacts your performance, whether you think you will be marginalized for your disclosure, and the possibility that the situation will eventually resolve itself, said Rosalind Joffe, a career coach who works with people living with chronic health conditions. If your work performance begins to suffer because of your health, it’s best to “stay out in front of the conversation,” said Joffe, whose own health conditions include multiple sclerosis, ulcerative colitis and glaucoma.

This can help prevent coworkers from jumping to incorrect conclusions from, say, your lateness to work, stumbling or looking fatigued — and, instead, suspect that you’re uninterested in your job or have a substance-abuse problem, she said. You might be better off providing a simple, matter-of-fact explanation of your condition, she said, focusing on how the illness impacts you rather than getting into the weeds of medical jargon.

Don’t divulge more than you need to. The less you tell your coworkers about your personal life, the more power you have to control your own narrative at work, said human-resources consultant Laurie Ruettimann. “Be real intentional in how you craft that story, and only give as much information as answers the question or addresses the problem,” she said. “You have to be your own PR agent.”

After all, she added, your colleagues are not your friends or family members, however much they might feel that way. It’s inappropriate to place that kind of weight on them, she said, and unwise to entrust your confidential information with someone who could later act in bad faith or accidentally violate your confidence.

If you need reasonable accommodations, speak up. “While it seems like it’s going to hurt to ask, asking is the first step to getting you what you need — so please ask,” employment attorney and HR consultant Kate Bischoff said. Talk to your physician about what you can and can’t do in the workplace, she added, and then initiate a conversation with your supervisor or HR department about arranging accommodations.

Arrive with a plan for the kinds of “workarounds” that might be realistic within your work setting, added Joffe, “so that it doesn’t fall on someone else to figure out how you can do your job.” For example, do you need work flexibility, a standing desk or a work space closer to the restroom? (The federal Office of Disability Employment Policy’s Job Accommodation Network is a helpful resource.)

In formulating such a plan, envision worst-case scenarios for how your condition could impact you at work — and then include potential solutions to those problems, Ruettimann said. Seek guidance from colleagues who you know have navigated your organization’s accommodations process, she added, and tap into your employee-assistance program (EAP) for advice.

But remember: “It’s only going to work if you can do the job as it is currently described,” Joffe said. “You’re going to end up most likely losing that job, one way or another, if you can’t do it. Only you know what your capacity is.” If you believe you can do it, then go ahead and plan for your return to work, she said — with or without workarounds.

Be aware of how people perceive your ability to do your job. If someone is making an untrue or unfair assumption about you based on your illness, “you’ve got to be brave in the moment and call it out,” Ruettimann said. “Don’t be a jerk about it, but don’t let it slide — one assumption taken the wrong way becomes the norm.”

If you believe you’re being treated differently or discriminated against, your employer has a responsibility to fix the situation, said Bischoff. Ruettimann advised tackling the problem “as locally as you can,” whether that means saying something to the individual who is treating you differently, talking to HR, or escalating your complaint through your corporate HR structure’s chain of command. EAPs often provide coaching, advising, legal advice and financial resources, she added.

You can also file a charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and/or your state or local employment-discrimination agencies. But Joffe said that while the EEOC route “can be very effective if you have a very provable case,” it can be more complicated with an “invisible, waxing-and-waning chronic illness.” “I have never met anybody who has gone to the EEOC with a claim like that and had anything positive come out of that,” Ruettimann added.

If you have the luxury of being able to find a different job, that’s often the best option, Joffe said. Then again, if it’s only one or two people giving you trouble, sometimes “you’re better off staying in a place where they value you and they’ll work with you.”