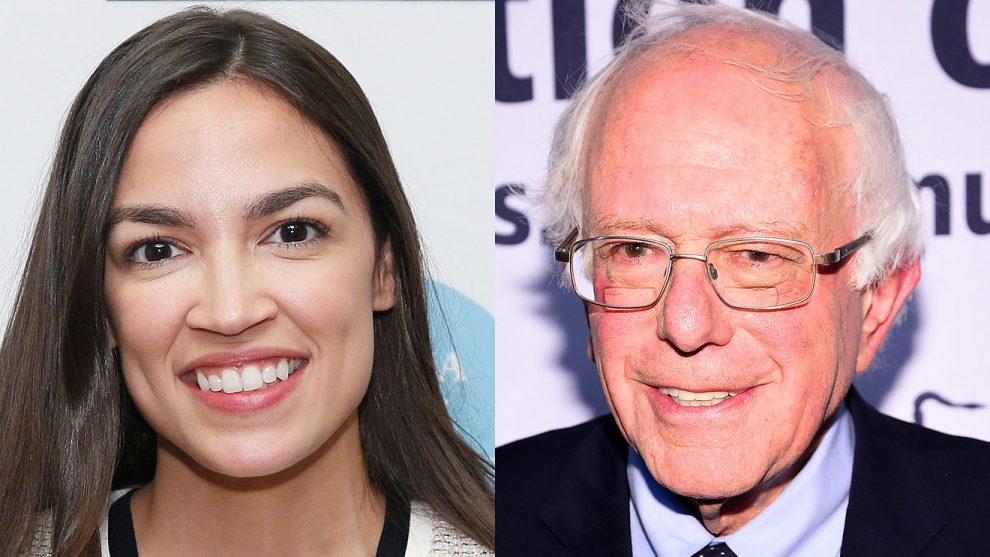

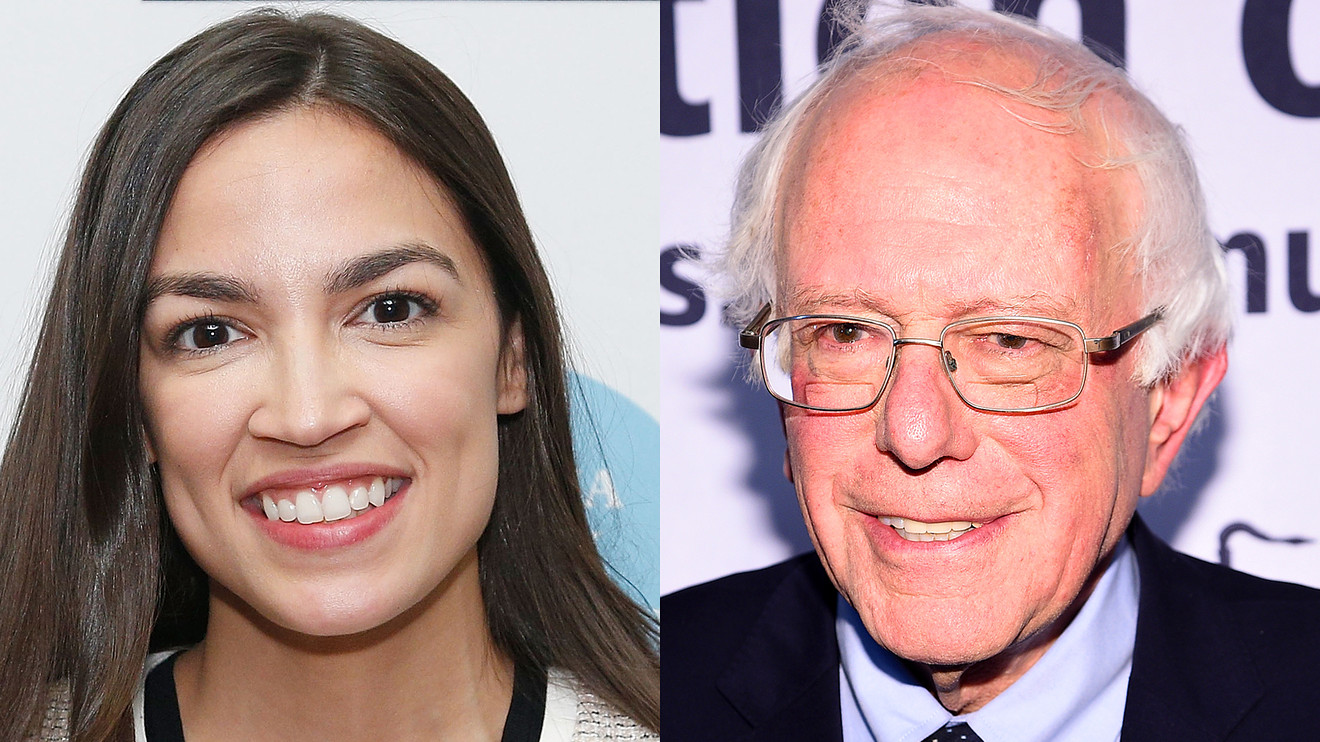

Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez want to cap interest rates on credit cards and other loans at 15%. But such a plan wouldn’t just hurt banks — it could also have major consequences for consumers.

Sanders, an independent senator from Vermont, and Ocasio-Cortez, a Democratic representative from New York, plan to introduce legislation they have dubbed the “Loan Shark Prevention Act.” The bill would establish, among other things, a 15% cap on credit-card interest rates and allow states to create lower limits. Currently, the average credit-card interest rate is at a record high of 17.73%, according to data from CreditCards.com.

In defending the proposal, Sanders described bank issuers’ interest-rate practices as “grotesque and disgusting.” “You have Wall Street and credit card companies charging people outrageously high interest rates when they are desperate and they need money to survive,” Sanders said. He’s cited past precedent as support for the cap: In 1980, Congress established a 15% cap on credit union interest rates. At one time, interest-rate limits or “usury caps” were common across the U.S.

Creating a new lower limit on the credit-card interest rates could lead to a whole host of changes that may negatively affect consumers. “No one benefits from this cap,” said Odysseas Papadimitriou, chief executive of personal-finance website WalletHub. “Fifteen percent is major, as the average interest rate is higher than that for everyone except people with excellent credit. So the cap would lead to a lot more expensive alternatives to a lot of consumers.”

Here are some of the ways the plan from Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez could backfire, if it were to be passed by Congress:

It could spell the end of credit-card rewards

When the Durbin Amendment of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act went into effect in 2010, debit-card rewards all but ceased to exist. The amendment capped the interchange fees debit-card issuers could charge to retailers. Banks had used the revenue from those fees to finance the debit rewards programs — so when that well ran dry, the programs were terminated.

A similar fate could await credit-card rewards if interest rates were capped, said Matt Schulz, chief industry analyst at personal-finance site CompareCards.com. “Anything that hits banks’ bottom lines hard, as this certainly would, could lead to less lucrative credit card rewards,” he said. “Banks are already a little queasy about the high cost of the rewards arms race, so taking a big bite out of their interest revenue certainly wouldn’t help.” Nor is this proposal as unusual as one might think.

Until the 1970s and 1980s, most states had usury caps for consumer loans, and some still do for payday loans, according to the National Consumer Law Center. But a 1978 Supreme Court decision allowed banks to charge their home state’s interest rate to customers at the national level, which prompted some states including South Dakota and Delaware to abandon their limits in order to attract banks to set up shop there. Federal lawmakers subsequently passed deregulatory legislation to loosen lending amid the double-digit inflation in the 1980s.

Also see: Why companies from T-Mobile to SoFi want to get into banking

It could lead to an increase in the fees charged to card holders

Banks would want to maintain credit-card rewards programs if at all possible because they’re an easy way to differentiate a credit card and give it an advantage over competitors’ offerings. So card issuers could look to other ways to generate revenue that will support these rewards programs — and raising fees on consumers would likely be one of their main tactics.

Ted Rossman, industry analyst at CreditCards.com, compared the hypothetical situation to the airline industry. “Airlines are really good at nickel-and-diming passengers, too,” he said. “When costs like employee salaries and gas prices rise, airlines look to make that up through bag fees, seat assignment fees, etc.”

See also: Flight fees are on the rise — here’s how to avoid them

More cards would likely come with annual fees in such a scenario. But other new fees could be instituted, too, such as fees to get a higher credit limit. And existing fees such as late-payment fees would probably go up, said Brian Karimzad, co-founder of personal-finance website MagnifyMoney.

It could reduce access to credit for low-income consumers

One reason credit-card issuers charge high interest rates is to offset the risk they take on by lending to consumers with thin or riskier credit histories. “Card companies take great care to assess risk through credit scores and other methods, and this is why they say they need to charge higher interest rates to cardholders with lower credit scores because they might not get paid back, and unlike a mortgage or auto loan, there’s no asset on the line as collateral,” Rossman said.

As a result, a 15% credit-card APR cap could compel these companies to be stingier when it comes to approving people for credit cards. Lenders like Chase JPM, -2.35% Bank of America BAC, -3.92% and Capital One COF, -2.61% were more cautious about approving credit cards in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession.

(Chase and Bank of America declined to comment on the proposed legislation. In response to the announcement, the American Bankers Association’s senior vice president Jeff Sigmund said the proposal “will only harm consumers by restricting access to credit for those who need it the most and driving them toward less regulated, more costly alternatives.)

Read more: Ask these questions about your credit card — it could save you hundreds of dollars

In particular, retailers may need to curtail their store credit card offerings. These cards on average carry an interest rate of nearly 30%, according to CreditCards.com. Interest rates on these cards are higher generally because stores offer the cards on the spot without doing any underwriting to guarantee a consumer’s ability to repay their debt. As a result though, they’re fairly unpopular with consumers.

Nevertheless, retail cards can be an important tool for consumers to build up their credit history, especially if they eschew the high interest rates by paying their balance in full each month.

Industry experts suggested consumers who can’t get credit cards may turn to personal or payday loans instead. The proposal from Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez would also limit interest rates on these loans. However, these loans can be costlier because the payments are generally set at a higher amount each month than the minimum payment on a credit card and loan origination fees can add up substantially.

“A lot of people would be shut out of credit cards as an option entirely,” Papadimitrou said. “Those people will then be forced to borrow from more expensive sources.”

Shares of card networks Visa V, -2.04% and Mastercard MA, -2.20% are up 20% and 28% year-to-date, respectively. Comparatively, the S&P 500 SPX, -2.27% is up 12% during that same period, while the Dow Jones Industrial DJIA, -2.25% is up 9%.

This story was updated on May 13, 2019.