Louise Rausa, 72, lived in world-class cities including Paris and New York, and she spent part of her adulthood in co-housing communities in the western United States where residents shared a kitchen, garden and outdoor space.

So when it was time to retire, there was little chance that a sedate retirement community would make a suitable destination for the active, now-single Rausa, who shares her knowledge of cuisine in workshops for neighbors and regularly hosts her grandchildren.

A little over two years ago, the former registered nurse opted for an apartment in North Hollywood, Calif.’s NoHo Senior Arts Colony, where hallways are a rotating gallery, studio space is available for residents to mix their own paints and a theater occupies the ground floor. In true Angelino style, Rausa owns a car and parks it on site, but she can walk around her high-density neighborhood or take mass transit.

Evergreen Real Estate Group in Chicago

Evergreen Real Estate Group in Chicago

Some of the most notable features? “Salon-style discussions of history and politics with ethnic food to share and personal IT help for residents,” says Rausa.

The downsides? “There could be more grab bars [for support], and the rent goes up about $35 a month every year. For [neighbors] on a limited income, that does not keep up with COLA [the annual cost-of-living adjustment].”

In fact, that estimation may be understating what has been a steady creep higher for senior housing costs, especially in robust real-estate markets such as California, where the Department of Housing and Urban Development has allowed subsidized senior rents to float higher, capped at increases of 11% a year, alongside price gains in the overall market, says Michelle Coulter, director of operations with Meta Housing, the developer of the NoHo project.

Little doubt it’s the evolving priorities of Rausa and her contemporaries, including the financial burdens associated with living longer than prior generations did, that challenges a U.S. formula for senior housing that hadn’t changed much in decades. Yet if the demanding, savvy-consumer baby boomers taking over where their Depression-era parents left off have their say on where and how they live as they age — and geriatrics experts say they do — the era of grin-and-bear-it acquiescence is no more.

NoHo Senior Arts Colony

NoHo Senior Arts Colony

Today’s target market for senior housing comprises a large and influential demographic. The number of households with people age 80 and over jumped 71% from 4.4 million in 1990 to 7.5 million in 2016, according to Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies in its “Housing America’s Older Adults” report. As baby boomers age, the number of households in this group will more than double by 2037.

Many of today’s best available senior-housing options are really a nod to the past: higher-density locales, homes suited for multiple generations, and community support and stimulation that keeps retirees active and healthy.

Until recently, U.S. senior-housing solutions have largely consisted of cookie-cutter developments demanding big upfront deposits from residents who might eventually face a new round of stress in seeking high-level, and usually expensive, nursing-home care elsewhere, says Jane O’Connor, principal at 55 Plus LLC in Charlemont, Mass., a consultancy focused on senior housing and lifestyles.

The cost of long-term-care insurance has skyrocketed due to factors including actuarial longevity and persistently low interest rates hurting insurers’ portfolios. That means, in many cases, when an individual can no longer live alone or rely on a spouse or partner, the next stage for care has mostly involved uprooting seniors to move in with family members who had not banked on the arrangement.

Reliving your 20s? Yes, and no

It’s clear that the U.S. is little match for Europe when it comes to rethinking elder care. The Netherlands, for instance, is home to a memory-care village, a complete indoor-outdoor community for dementia patients. Holland has also piloted a program pairing affordable-housing-seeking college students as roommates with companion-seeking seniors.

The needs and likes of these age groups aren’t so varied. In fact, it’s where, as much as how, seniors live that may take a page from the millennial and Generation Z handbook: a migration back into cities and denser suburbs for an active lifestyle and readily available services, according to architecture firm Perkins Eastman. In a survey it conducted in early 2019, 26% of client firms that build and redevelop properties for seniors says they believe boomers will be most concerned with living in proximity to an urban location or town center, up from 19% in 2017.

Evergreen Real Estate Group in Chicago, for example, is developing three urban projects that include a technology-focused, all-ages public library and media center on the ground floor topped by three stories of affordable senior rental apartments.

Annual income for eligibility is capped at $38,000 per person. Some units are supported with rental-assistance subsidies, while others rent at $740 monthly for a one-bedroom and $890 for a two-bedroom apartment. In at least one instance, a green roof and a terrace inject outdoor space, while a busy public-transit corridor and a substantial public park with tennis courts, ice rink and other programming are easily reachable.

“There is certainly a move back to the city among a lot of groups, including a population of seniors who maybe left when they had kids, but always wanted to move back,” says David Block, director of development at Chicago’s Evergreen. “It’s part of a broader move in real-estate development that says the way we built cities, with commercial space below and then we lived ‘above the store,’ so to speak, well, there’s a certain amount of wisdom in that.”

Evergreen Real Estate Group in Chicago

Evergreen Real Estate Group in Chicago

What’s more, builders and remodelers in urban, suburban and rural destinations alike are increasingly meeting seniors where they already live, creating space to entertain grandchildren, installing the bulk of kitchen storage at reduced heights and creating barrier-free entries that are seamless with the landscape, says O’Connor of 55 Plus in Massachusetts.

How technology is helping

And then there is a rethinking of senior housing at the personal level. Technology, especially leveraging the sharing economy, can help satisfy boomers who want to age in place or are rightfully demanding more from their assisted-living options. (Think of services spanning Uber or Lyft rides to in-home wellness programming.)

“Transportation-on-demand, dining-on-demand and online learning are all trends that really play well in the senior market,” says Dan Hutson, chief strategy officer for the Los Angeles–based nonprofit HumanGood, one of the U.S.’s largest senior-living-community owners and operators. “Giving priority to voice-first technology [such as Amazon’s Alexa and its rivals] over even mobile-first technology is tailor-made to serve older adults.”

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Age Lab, in a report, showed that for a single 85-year-old homeowner living without significant physical or financial distress and without a mortgage, the total cost of living at home using sharing-economy services for one month was $2,967. Compare that with an assisted-living model in the Boston metropolitan area (including meals and housekeeping), which runs $6,433 a month. The report did discover a tech learning curve, especially given how fast next-generation updates are required, and conceded that security and privacy compromises were off-putting for some.

The sharing economy has a place at the provider level, too, says HumanGood’s Hutson. “With food delivery, who says that a senior-living community even has to have a commercial kitchen? Or a fleet of vans? You can virtualize a lot of that and reallocate those dollars to other aspects.”

And in health care, virtual exchanges will only gain in popularity. Telehealth — video check-ins or the use of monitoring technology to share information with a health-care professional — is already filling gaps in rural communities. It reduces transportation barriers for seniors and mitigates health-care costs by, for example, reducing emergency-room visits for more easily diagnosed ailments and blood-pressure checkups, all toward the end of helping seniors remain in their homes. In early 2019, AT&T, for one, rolled out a smartwatch, OnePulse, designed with telehealth and remote patient-monitoring capabilities.

Powerful Wi-Fi connectivity and personal technology also influence much of the design in higher-income senior housing, says Justin Dickinson, vice president of investments with CA Senior Living LLC. The Chicago-based company has luxury retirement complexes in several major U.S. markets typically available to singles or couples with incomes well over the $35,000 household median at age 75 (according to U.S. Census data) and funded in part by a home sale, other investments and income, or long-term-care insurance. On the recreational side, active-lifestyle technologies can mean golf simulators. But there are health and security applications as well: geospatial intelligence wearables for residents — similar to Fitbit exercise trackers — which can help with fall prevention, wandering neighbors, even appointment reminders.

‘Aging in community’

Many seniors say they prefer “aging in place” instead of moving in with family or packing up for multistage assisted living. Amy Schectman, chief executive officer at 2Life Communities, which serves the housing needs of about 1,500 mostly low-income seniors in the Boston area, says “aging in community” is more important. That’s because isolation is a serious health danger. It’s a bigger threat than obesity and smoking, and can double the rate of dementia, she says.

Inclusion, says Schectman, can present itself in the most low-tech of ways. She recalls resident “Rose,” a dementia sufferer who maintained a social life in a 2Life facility simply because friends of long standing kept a weekly date on Mondays for a mock bridge game to provide her companionship, and then played a competitive game on Tuesdays without her.

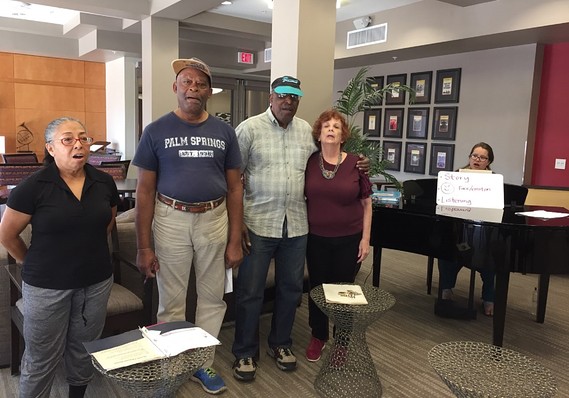

Louise Rausa

Louise Rausa

For budget-minded Schectman, her sharing-economy approach is micro; she’s piloting a program in which residents take on roles in reception, dining or continuing education, for instance, in order to cut down on the costs of paying for staff in those positions and at the same time reinforcing a sense of community.

For some seniors, the multistep model of transitioning from independent living to assisted living to intensive nursing and memory care, but all on the same campus, will be the best and only option. That’s true for Phillip Beluscheck and his wife, Marilyn, both 89 and living since 2017 in Aspired Living of Westmont, outside of Chicago, after 50-plus years in the same family home.

Their move, endorsed by Phillip Beluscheck as “no place is perfect, but this is pretty close,” was expedited in part as a boomer daughter began splitting time between Florida and Illinois. And, importantly, their selection could be financed by Beluscheck’s careful retirement planning. The former executive at General Motors — who now regularly educates an Aspired Living audience on the technology behind driverless cars — collects a corporate pension, supplemented by the sale of the couple’s nearby suburban home and an income-generating stock portfolio to cover a $7,400-a-month apartment. The new home features a kitchenette, any-time meal service in a community dining room, maintenance, shuttle service, fitness facilities and programming, and some medical checkups and prescription management, among other amenities.

Being mindful of affordability, service quality and socialization will drive the impetus for crafting coming decades’ menu of senior housing solutions. That includes variety in multistep models, looser zoning for multigenerational homes, as well as a resourceful sharing economy and neighborhood services.

“The 1990s was a big explosion of continuing-care retirement communities, [where] design was predetermined, and you had to buy in early with a hefty deposit. They were tribal — like the country-club set — but boomers don’t like this model,” O’Connor of 55 Plus says.

“These are the children [raised by] the ‘Because I say so’ generation,” says O’Connor. In rebellion, and with many more options, “they’re going to retire just how they want.”

Read more of the Best New Ideas in Retirement

• This is how much you need to save for retirement

• Long-term care insurance is a dying industry. Here are new ways the high costs of aging

• How robots and your smart fridge can help keep you out of a nursing home

• You’re probably not ready to retire — psychologically

• Retirement is an emotionally and financially charged life stage — ignore it at your peril