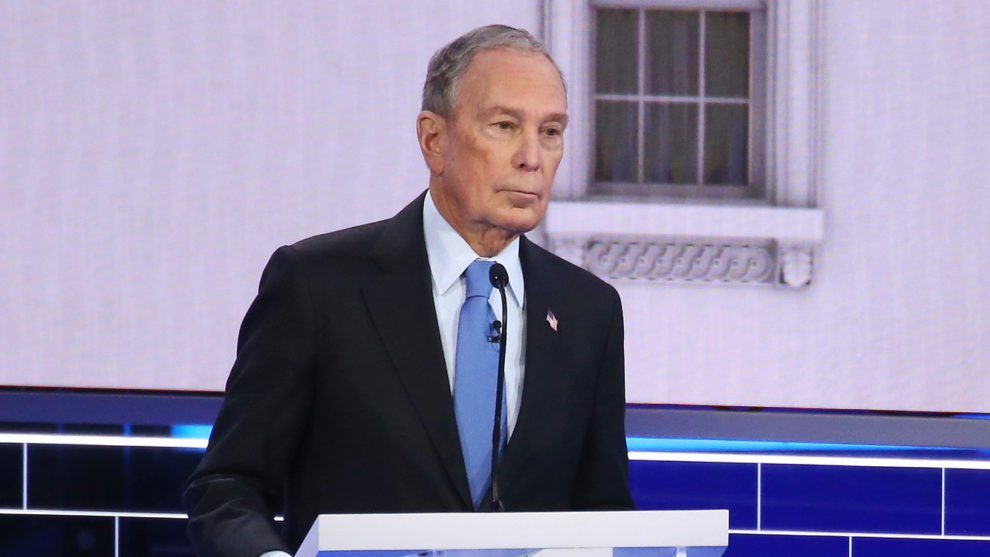

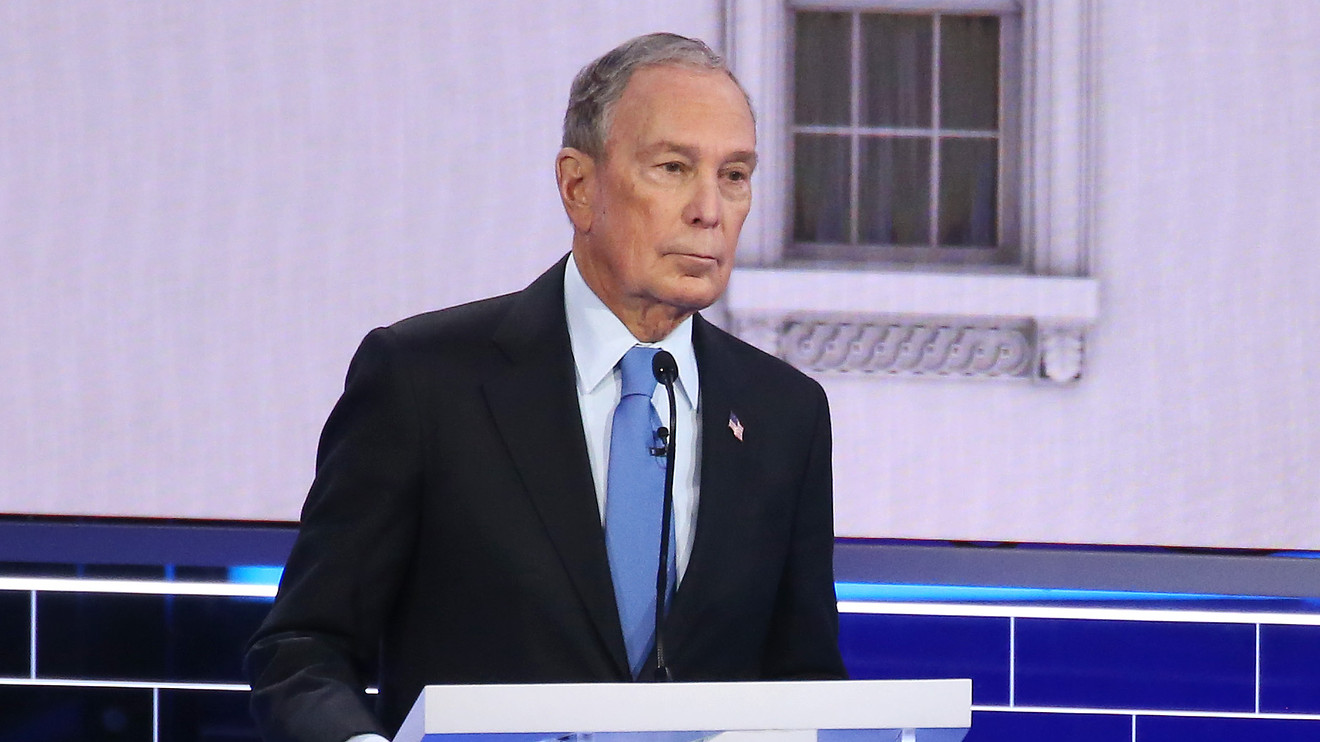

In addition to clashes over nondisclosure agreements and policing practices, Sen. Elizabeth Warren and former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg squared off during Wednesday night’s Democratic presidential debate over the mayor’s past comments regarding discriminatory housing policies.

“When Mayor Bloomberg was busy blaming African-Americans and Latinos for the housing crash of 2008, I was right here in Las Vegas, literally just a few blocks down the street, holding hearings on the banks that were taking away homes from millions of families,” the Massachusetts senator said.

The Associated Press last week resurfaced statements Bloomberg made in 2008 during a forum at Georgetown University, linking redlining to the financial crisis roiling the nation at the time.

“It all started back when there was a lot of pressure on banks to make loans to everyone,” Bloomberg said at the time, according to the AP. He argued that legislative efforts to end the practice of redlining, which he described as banks telling their salespeople not to go into poor areas, led the country toward financial collapse because “banks started making more and more loans where the credit of the person buying the house wasn’t as good as you would like.”

Bloomberg campaign spokesman Stu Loeser told MarketWatch, “Mike wasn’t in any way supporting redlining and, in fact, fought hard against predatory lending as mayor and helped other cities find ways to keep people in their homes as a philanthropist.”

“As a candidate for President, he has detailed plans for how he will help a million more black families buy a house, and counteract the effects of redlining and the subprime mortgage crisis,” Loeser said. “His plan will provide down-payment assistance, get millions recognized by credit scoring companies, enforce fair lending laws, reduce foreclosures and evictions, and increase the supply of affordable housing.”

Read more: The rent is too damn high — even for middle-income Americans

The term redlining refers to the denial of financial services to neighborhoods typically populated by people of color. In particular, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation drew up color-coded maps that designated how risky it was for lenders to originate mortgages in different neighborhoods across the country. The most risky neighborhoods were outlined in red, and those neighborhoods tended to be predominantly black.

‘The crisis was absolutely not caused by the ending of redlining laws. The crisis was caused by the proliferation of unsustainable mortgage products that flooded the market and caused people to be put in a situation where there was no feasible way for people to afford their mortgage.’

The Federal Housing Administration also used these maps in determining whether loans could receive insurance. Redlining was officially outlawed through a series of legislation passed in the 1960s and 1970s.

“The [financial] crisis was absolutely not caused by the ending of redlining laws,” said Lisa Rice, the president and CEO of the National Fair Housing Alliance. “The crisis was caused by the proliferation of unsustainable mortgage products that flooded the market and caused people to be put in a situation where there was no feasible way for people to afford their mortgage.”

During Wednesday’s debate in Las Vegas, Bloomberg walked back his 2008 comments, arguing that he is “well on the record against redlining.”

“I was against it during the financial crisis, and I’ve been against it since,” he said. “Redlining is still a practice in some places, and we’ve got to cut it out.”

While the practice of redlining was officially outlawed, people of color still face discrimination in the U.S. real-estate market. For instance, a recent investigation by Newsday uncovered evidence that many real-estate agents in Long Island, N.Y., continue to steer clients to neighborhoods based on their race or ethnicity. This analysis of 61 metro areas by Reveal News also suggests the practice still exists.

Here are some of the lasting effects the discriminatory policy still has on the country’s housing market:

Home prices are still lower in previously redlined neighborhoods

A 2018 study from Zillow ZG, +2.21% found that a home located in an area given a “hazardous” rating in the 1930s is still only worth 85% of the median value of a home in a nearby, non-redlined neighborhood.

As a result, black Americans who are homeowners in these areas haven’t seen the same wealth-creating benefits of rising home values as their peers in other places. Researchers argue that this had exacerbated the racial-wealth gap.

Boosting the returns on homeownership for black families would reduce the wealth gap with white families by more than $17,000, or 16%, according to a 2015 report from the public-policy organization Demos and the Institute for Assets and Social Policy at Brandeis University.

Gentrification caused the displacement of nearly 111,000 black Americans between 2000 and 2013.

Those lower home prices have also become a double-edged sword in recent years in certain parts of the country, paving the way for gentrification in increasingly unaffordable cities like New York and San Francisco.

White residents have moved into once-redlined neighborhoods because of the lower rents and property values. For long-term black and Latino residents — many of whom earn lower salaries and have less wealth than their new neighbors — this turn of events has meant that they can’t afford rising property taxes.

“People have found it hard to keep up with those elevated property values,” Rice said, “and they have to sell and leave their property or they lose their property through tax foreclosure.”

Gentrification between 2000 and 2013 led to the displacement of some 135,000 people across the country, including nearly 111,000 black residents, according to a 2019 report from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

People of color still face more difficulty accessing credit

In 2016, African-Americans made up 13% of the country’s population, but only received 6% of the mortgages that were originated that year, according to a MarketWatch analysis of Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data that demonstrates whom lenders are serving.

In the wake of the financial crisis, mortgage lenders have implemented more stringent standards for determining who should receive a loan. To some extent, those efforts were mandated by law, but consumer advocates argue that lenders are being too picky when it comes to determining who is creditworthy.

These stricter standards represent a major hurdle for people of color, who generally have lower credit scores than their white peers. Part of why they have worse credit scores is because of where they live. A “dual credit market” exists across the country, Rice said.

African-Americans represent 13% of the U.S. population, but only got 6% of all mortgages in 2016.

“Still today, predominantly African-American neighborhoods do not have bank branches, while predominantly white neighborhoods are well-resourced with branches of mainstream financers,” she said. “Bank are closing branches in high-income affluent black neighborhoods at a higher rate than they are closing branches in low-income non-black neighborhoods.”

Rather than by bank branches, majority-minority neighborhoods tend to be serviced by check-cashing companies and payday lenders, whose practices have been criticized as predatory. Many of these companies don’t report positive credit information to the major credit bureaus, Rice said, making credit-building more difficult.

Without physical access to traditional financial services, it is extremely difficult to build one’s credit by getting a credit card or another type of loan.

The low access to credit means that black and Latino consumers are less likely to be homeowners. The homeownership rate among black Americans was just 44% as of the fourth quarter of 2019, and the rate among Hispanic Americans was only slightly higher at 48.1%, per data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Comparatively, nearly 74% of white American households are homeowners.

The financial crisis continues to impact communities of color

Black homeownership hit an all-time high ahead of the housing crisis, reaching nearly 50% in 2004. But black households faced foreclosure at much higher rates than white households — a reflection of the predatory lending practices that had targeted communities of color during the housing boom.

Since then, the homeownership rate among black households has dropped to an all-time low.

To this day, foreclosure rates are centered on working-class neighborhoods, many of which are predominantly black or Hispanic. In 2019, 56% of properties that went to foreclosure auction were in low-income census tracts, even though these areas only represent a fifth of all neighborhoods nationwide, said Daren Blomquist, the vice president of market economics at Auction.com.

“A lot of the communities that were redlined got the short end of the stick,” he said.

div > iframe { width: 100% !important; min-width: 300px; max-width: 800px; } ]]>