There is plenty of crony capitalism in America today.

There are thousands of instances of companies lobbying for tariffs, price supports, subsidies and restrictions on their competition, all for their own self-interest and profits. When such lobbying is successful, capitalism becomes about sucking up to power and cultivating the coercive powers of the state to be on one’s side, rather than about lowering costs, lowering prices, improving quality, and serving consumers.

The footprint of crony capitalism appears especially prominent these days because of President Trump, who is a pre-eminent practitioner of the doctrine. Donald Trump spent his career in business and during the 2016 primaries boasted of how he paid off politicians for favors and special access. His main businesses — real estate and casinos — typically rely on getting permission from varying levels of government to build and then open something,whether it be apartment blocks, corporate suites, or a new venue for boxing or gambling.

All that said, the data just do not support the view that big business is the dominant force shaping American government. For instance, corporations spend about $3 billion a year lobbying the federal government. That sounds like a lot of money, but it is very little in comparison to the approximately $200 billion they spend each year on advertising. To put the $3 billion in perspective, that is about equal to how much General Motors spends on advertisements during a year; Procter & Gamble is higher yet, spending $4.9 billion a year on advertising.

The Citizens United Supreme Court decision of 2010 has contributed to the impression that corporations are all-powerful in American politics. After all, a company, whether for-profit or nonprofit, can now spend money on campaigns and “electioneering communications” without general restrictions. But in fact Citizens United is one reason big business has lost influence in Washington. Individuals, too, can now spend billions of dollars to attempt to advance their intellectual and ideological agendas. While most of these individuals are businesspeople and earned their money through business, being a donor on that scale selects for those businesspeople who have very strong ideological commitments. No matter what you think of the Citizens United decision, it seems to have heralded an era in which the influence of ideology is rising, and the role and power of mainstream business is diminishing.

Arguably business is more influential through lobbying than through campaign contributions, but even there the numbers are less intimidating than many people might think. As of 2007 (I cannot find more recent exact numbers), the average big company has only 3.4 lobbyists in D.C., and for medium-size companies that same number is only 1.42. For major companies, the average is 13.9, and the vast majority of companies spend less than $250,000 a year on lobbying. Furthermore, a systematic study shows that business lobbying does not increase the chance of favorable legislation being passed for that business, nor do those businesses receive more government contracts; contributions to political-action committees (PACs) are ineffective too.

Caroline Baum: Crony capitalists are the big winners in Trump’s trade war

If you are looking for a villain, it is perhaps best to focus on how corporations sometimes help poorly staffed legislators evaluate and draft legislation. But again, national policy isn’t exactly geared to making businesses, and particularly big business, entirely happy.

Look at the main features of the federal budget. The two biggest programs are Social Security and Medicare, both of which are extremely popular with the American public. And since the elderly vote at disproportionately high rates, politicians usually compete to defend and extend these programs.

Surely lobbying by hospitals and doctors is one major reason Medicare costs so much; for instance, Medicare is prohibited from negotiating to drive down the prices of prescription drugs, and hospitals have forced into federal policy a high-cost model for American health care. That’s one of the biggest influences of corporations on the federal budget, but it is very much within a voter-driven context.

Read: Peter Morici says let the states experiment with competing health-care approaches

Next in line in the federal budget are defense spending and interest on the national debt. Defense spending is bloated by the influence of military contractors on the procurement process, but a lot of the costs the military incurs are labor and pensions, not capital spending. Furthermore, defense spending tends to be politically popular, even when weapons systems are costly. Few politicians get very far by running against defense spending as a major issue.

Finally, interest on the debt isn’t a corporate issue at all.

Farm subsidies are the clearest and most egregious example of a government policy driven almost completely by corporate special interest groups. But even those subsidies are “only” about $20 billion a year (varying with market conditions), out of a federal budget of more than $4.4 trillion.

Read: There’s no looming farm crisis — so there’s no reason to even consider more subsidies

Or consider the regulatory apparatus. You can tell thousands of tales of businesses shaping regulations for their benefit, evading regulations, persuading regulators not to enforce statutes on the books, and so on. Yet businesspeople are almost always very unhappy about the current state of regulation. Most of them feel they are regulated by the government far too much, and indeed there is a lot of independent evidence that regulations, whether or not you favor them on net, do indeed impose fairly high costs on American business.

St. Martin

St. Martin

Above and beyond the direct compliance costs they are a significant drain on the attention and energy of CEOs. It is pretty common to find estimates that the regulatory burden involves direct business costs of trillions of dollars a year, and some of this (we don’t know how much) eventually gets passed along to consumers. I don’t think we have a good grasp of these regulatory costs, but I hardly think of regulation as an area where business is getting its way, and I do believe those regulatory costs are in fact very high.

Despite all the deregulatory initiatives of the Trump administration, the overwhelming majority of regulations are still in place and are not going away anytime soon.

Finally, keep in mind that corporate influence on government is by no means always bad. When it comes to the major issues those companies report lobbying on, taxes, trade, immigration and copyright are high on the list. In my view, when it comes to trade and immigration, that lobbying is arguably beneficial, but on copyright it is somewhat less so, and on taxes it is mixed.

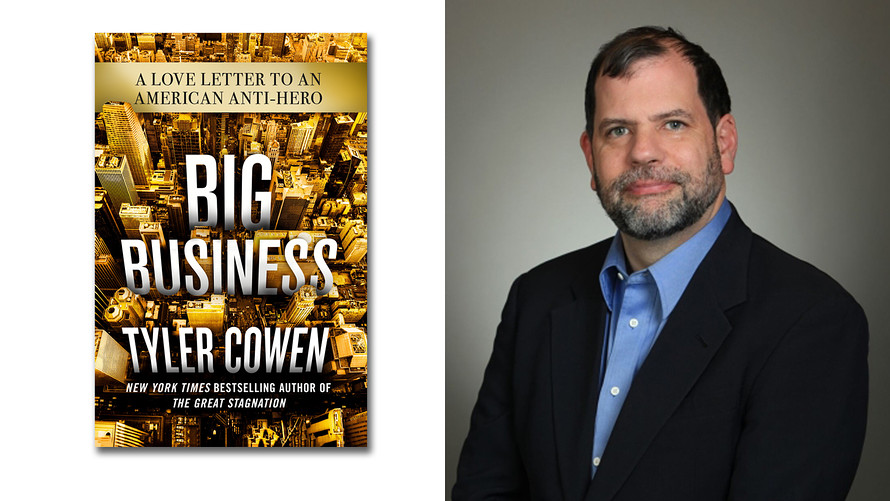

Tyler Cowen holds the Holbert L. Harris Chair in Economics at George Mason University. This is adapted from his book “Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero.” Follow him on Twitter @tylercowen.