We often hear HR executives and hiring managers claim that they fully support diversity efforts and are committed to hiring the best person for the job regardless of demographic characteristics, as long as they’re the “right fit” for the position. These professionals may be well-intentioned, and we have no doubt that they believe they are advocates for gender equity. But if this is true, then why is there such slow progress to eliminate persistent industry and organizational gender inequities?

One thing is clear, simply believing in gender inclusion doesn’t always equate to desired outcomes. The well-known gap between knowing and doing in business helps to explain why hiring managers often believe they are hiring the best person for the job when in fact they perpetuate the gender status quo. Quite often, they lack the requisite knowledge and awareness of how their hiring practices are infested with unconscious bias, stereotypes, and faulty perceptions that keep them from seeing female candidates as the right choice.

The solution for hiring managers? Enhance your GQ — gender intelligence — and apply it to create transparency and accountability in employment processes.

When we say that “we want the best person for the job,” too often this means the person that I know or relate to, the person I am most comfortable with, or the person who looks like me. Instead, what if we flipped the script and asked, what’s keeping the best person from applying for or being selected for the job?

This type of introspection can help us to discover how our everyday practices and perceptions of others may be working against us. As we develop our gender intelligence, we become more aware of implicit and systemic biases, the effects of biases on employment outcomes, and how we can disrupt status quo practices to achieve desired results.

Understanding the distinction between systemic and implicit biases is key to developing our gender intelligence because it tells us where to look. Systemic gender biases are found in formal and informal processes that disadvantage women. These can include network-based recruiting, gendered job ad language, and subjective or ideal job requirements and qualifications. Recognizing and understanding how a process is systemically biased leads a hiring manager to consider how the process can be de-biased.

Implicit or unconscious bias operates when a person unfairly privileges someone from one group or disadvantages someone form another group. Implicit gender biases include the motherhood penalty, perception of women’s lack of competence in male-typed jobs, not valuing potential in women, seeing women primarily as caregivers, and focusing on unrelated personality (likeability) or image characteristics (body or clothing). Implicit biases require us to enhance our self-awareness as well as our awareness of others. In many cases, these implicit biases create blind spots in our appraisals of job candidates. Sharpening our gender intelligence makes us more self-aware and vigilant in recognizing bias in the moment.

This is not a difficult task if we know what to look and listen for. Everyday employment processes are rife with bias. Start by tuning in to red flag phrases such as: “I’m not sure that candidate is a good fit”; “His resume is really impressive”; “Sounds like she’s a busy mom”; “She’s not very likeable,” “I’d like to see her prove she can handle the job.”

Disrupting gender bias in the moment by calling it out is a clear sign of better gender intelligence. Hiring managers also need to consider how they can apply their enhanced gender intelligence to change hiring practices themselves to eliminate or reduce the effect of biases.

Here are four evidence-based recommendations:

1. Be purposeful in writing criteria in job ads: Research shows that women are less likely to apply for jobs that include language such as “aggressive” or “demanding”. Similarly, the use of masculine-gendered words can send the message to women that they don’t “fit” in a job and shouldn’t apply. There are easy solutions for screening this language using free- or commercially available text-editing programs that automatically filter for gendered language.

Additionally, be realistic in the job criteria listed in the job posting. Too often organizations will list the capabilities of the ideal candidate. While this sets a high bar, it also dissuades women from applying — but not men. Instead, consider listing minimum qualifications separately from preferred qualifications to help candidates distinguish essential from nonessential criteria.

2. Set clear, transparent and objective job criteria that can be consistently applied: Subjective or ambiguous job criteria is an invitation for bias. For instance, be alert for evaluations of “potential” or “talent” that lack clear operational definitions and tend to be assessed subjectively and inequitably across gender. If potential for growth or development is important in the job, then provide clear direction as to what experiences are valuable. Finally, be wary of shifting standards or criteria. Too often what becomes most important in hiring can be what “he” has.

3. Diversify and increase the size of applicant pools and short-lists: Often, well-meaning hiring managers will ensure that at least one woman is in the applicant pool or on the short-list. However, research finds that statistically she has 0% chance of being hired if she is the only woman. By adding just one more woman to the list, her odds increase significantly. Similarly, when hiring managers in a male-dominated industry are asked to add more names to their short list of final candidates, the result is more women are added to the list and hired.

4. Diversify and expand recruiting and advertising networks: Because men, especially white men, are more likely to be in positions of power and influence, they are also more likely to have more social capital. This social capital includes informal networks where formal (public) and informal (word of mouth) job leads are shared with other men and less likely to be shared with women. Men proactively contacting female colleagues and women in their networks to let them know that they would be great candidates, and to socialize this information with other women, can help overcome network differences.

Ultimately, the impact of making better hires reflects positively on the hiring manager and can lead to better career outcomes. Just as important, as they enhance their gender intelligence, these hiring managers become better leaders and colleagues. Moreover, hiring managers who successfully implement these actions do more than help their company achieve diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) goals. They also make their company more successful and profitable, and enhance their company’s reputation as a highly desirable workplace where diverse and talented people are valued.

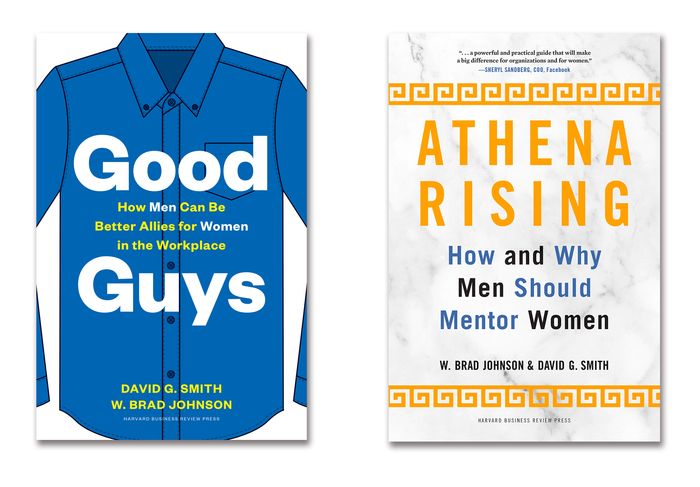

W. Brad Johnson and David G. Smith are the coauthors of “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace,” (Harvard Business Review Press, 2020), and Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women,” Harvard Business Review Press, 2019).

Johnson is a professor of psychology in the Department of Leadership, Ethics, and Law at the United States Naval Academy and a faculty associate in the Graduate School of Education at Johns Hopkins University. Smith is an associate professor in the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School.

Plus: Men must hold other men accountable when they see women being harassed. Here’s what you can do