People who are retired, or who are nearing retirement, are usually advised by financial professionals to keep a large chunk of their savings in bonds. That mainly includes U.S. Treasury bonds, state and local municipal bonds, and corporate IOUs issued by blue chip companies with strong balance sheets. Such bonds issue regular fixed payments, instead of the more uncertain returns you get from stocks.

The theory—and the mantra—behind this conventional wisdom is that bonds are better for senior citizens, because they’re “safer.”

Read: What’s the safest place for retirees to keep an emergency fund?

But older Americans might want to revisit that, following last week’s news.

Inflation fears have finally—at long last—broken out in the bond market. And it’s not pretty. Regular readers—all five of you—know I’ve been saying for months that the inflation forecast that matters isn’t the one from your hysterical brother-in-law or the one from some talking head on TV or radio, but the one in the bond market.

The one in the bond market involves real people—effectively millions of them—betting real money. So even though the forecasts embedded in bond market prices aren’t always right, they are rarely obviously wrong.

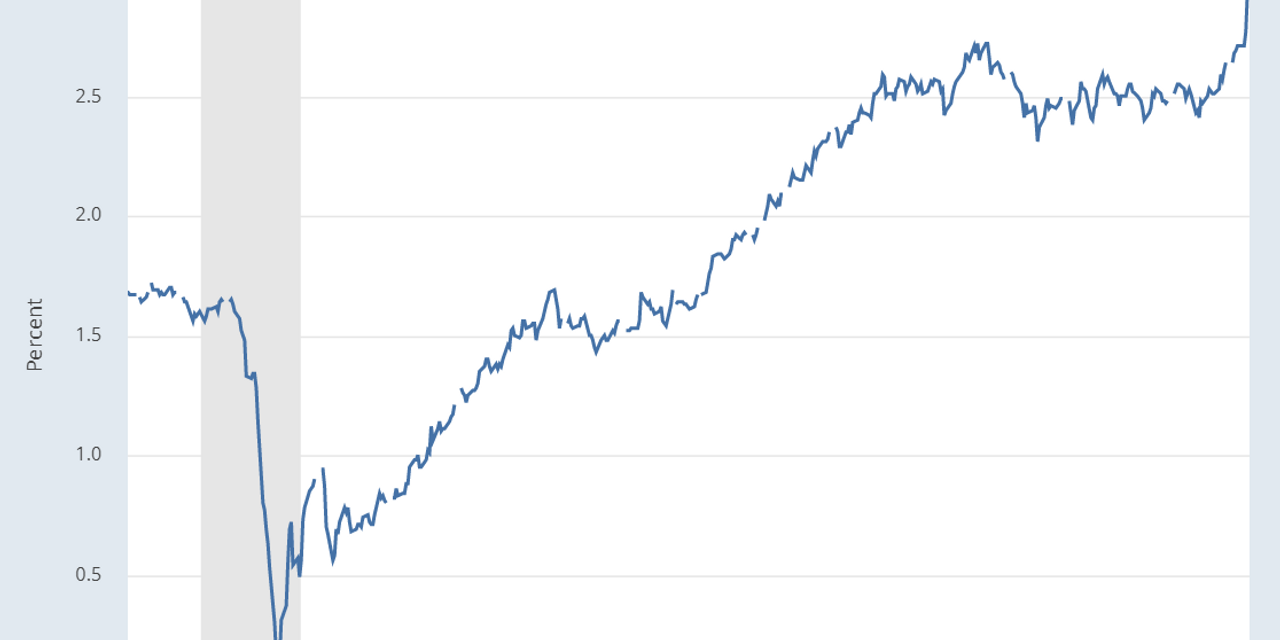

Last week the U.S. bond market’s prediction of U.S. inflation for the next five years leapt to 2.91% a year—the highest figure this millennium. That tops the inflation fears that surged in 2008, just before the financial crisis, and a previous peak in early 2005, when the housing market was out of control.

Read: 9 best Vanguard funds for retirees

And this forecast is nearly double what it was a year ago.

Granted, we are still a long, long way from the inflationary horrors of the 1970s, when inflation rates hit double digits (even if today’s empty supermarket shelves are starting to echo the infamous gas rationing and long lines at the pumps back in 1979).

And surging inflation may not happen anyway. Joachim Klement, strategist at Liberum, points out it’s no wonder inflation readings are currently high: Crude oil has nearly doubled in price in the past year. But inflation isn’t a one-off jump in prices. It’s a sustained rise in prices, year after year. Will oil double from here? Will it even remain where it is?

But.

Retirees today face a gigantic risk that their grandparents didn’t 50 years ago. Bonds.

Read: I failed at retirement. How to avoid my mistakes

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, bonds paid high rates of interest. So even though consumer prices were rising by 4% or 5% or 6% for most of the decade, the interest rate on bonds was still higher. So you had a cushion.

So for example in 1973, when inflation surged to 6.2%, 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds were paying 6.6% and BAA investment grade corporate bonds about 8%.

And in 1978, when inflation hit 7.6%, Treasurys were paying north of 8% and BAA corporates north of 9%. Bondholders still got hurt: Soaring inflation caused bond prices to tumble. And at the peaks, in 1974-75 and 1979-80, the inflation rate overtook their interest rates. But overall the bonds helped compensate them for higher prices.

Not today.

The interest rate on BAA bonds is now just 3.23%. That is less than half its lowest level during the 1970s. And the rate on the 10-year Treasury is 1.68% — barely a third of its 1970s low.

Bonds work like seesaws: When the price rises, the interest rate falls, and vice versa.

Right now bonds across the spectrum sport interest rates that are well below inflation. But, much worse, they are well below the inflation forecasts of the next five, 10 or even 30 years. And these are the low, low inflation forecasts everyone has been counting on for years.

So not only is there no cushion, but the reverse. (I suppose the opposite of a cushion is a hard place.) Even if inflation doesn’t rise, bondholders will lose money. And if inflation does rise, bondholders will lose a lot of money. Who wants to own an IOU paying less than 2% a year for the next decade if consumer prices are rising by 3% or more?

The Fed doesn’t want to freak out the stock market by raising interest rates. But can the Fed afford to freak out retirees and older Americans by not raising them?