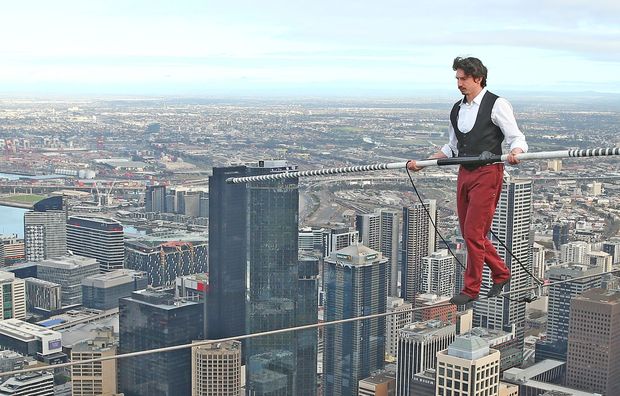

‘Balance’ is easy—until it isn’t (Photo by Scott Barbour/Getty Images)

Scott Barbour/Getty Images

You can do a lot with “averages.”

You and Amazon AMZN, +0.30% boss Jeff Bezos, for example, have an “average” net worth of about $100 billion. That’s true even if you don’t have a nickel to your name. He has about $200 billion, and there are two of you.

You and the Williams sisters, Venus and Serena, have won an “average” of 10 Grand Slam singles tennis tournaments each. That’s true even if you can’t hit a ball. They’ve won 30 between them, and there are three of you. So: Congratulations on those Wimbledon wins. Well done at the French Open. And so on.

Now here’s a brain twister. What sort of return should you expect in the years ahead on your retirement savings?

If you’re thinking somewhere between 7% and 9% a year, you’re in good company. Most of the managers of public pension funds, for example, are assuming they’ll get somewhere in that range. And that’s what conventional wisdom on Wall Street will tell you that you should get from a so-called “balanced portfolio” of 60% U.S. stocks and 40% U.S. Treasury bonds.

Where’s that number come from? Simple. It’s the historic…er…average.

Going back to the 1920s, for example, the average amount that so-called “balanced portfolio” earned in any given year was 9.0% (before taxes and fees).

Over the “average” 10 year period since then, allowing for variations, the “average” return was 8.7% a year.

So shouldn’t we expect that going forward?

We should be so lucky.

Wall Street money manager and Jeremiah John Hussman this week warned that because of sky-high stock and bond valuations the likely return from a 60/40 portfolio over the next 12 years is going to be negative, after counting inflation.

“Even based on corporate fundamentals that were in place at the February peak, 2020 is the first time in history that our estimate of prospective 12-year returns has been negative for this portfolio mix,” he writes.

Hussman, to be sure, has been a perma-bear for over a decade. But his analysis isn’t simply based on opinions, which are subject to disagreement, but math, which isn’t.

Everyone’s entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts, as the late senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan said.

We don’t have to rely on Hussman’s calculations, either. We can run a much simpler analysis of our own. Yale finance professor and Nobel laureate Robert Shiller tracks data on U.S. stock and bond prices going back to 1871, when Ulysses S. Grant was president.

In a nutshell: Based on his data, the 60/40 portfolio today is about as expensive in relation to fundamentals as it has ever been on record. It is valued at about three times the “average” price. So in what world can we expect “average” returns?

Since Grant’s first term, 10-year U.S. Treasury TNX, +2.76% bonds have yielded 4.53% interest a year…on average.

Today? Oh, 0.8%.

And since then the S&P 500 SPX, +0.61% index or its equivalent has produced an earnings yield of 7.33% — on average. Meaning that if you bought $100 worth of stock, on average your investments would have earned about $7.33 in net, after-tax income in the first year.

Today? From Shiller’s data, the earnings yield is around 3.1%.

Put all this together, and the current yield on a 60/40 portfolio of US stocks and bonds is around 2.2% — barely one-third of the historic average.

Yet, miraculously, many are hoping to earn, well, the historic average.

As there is no way on God’s green earth to squeeze 4.5% a year for 10 years out of a 10-year bond with an 0.8% yield, the miraculous feat of portfolio levitation will have to come from stocks.

What does that mean? The S&P 500 will have to earn 14.5% a year for the next decade for a balanced portfolio to earn 9% a year. It will have to earn just over 11% a year just for the overall portfolio to earn 7% a year.

Yet apparently many investors are hoping for this at the same time they are expecting inflation to remain at 2% or even lower.

If U.S. stocks produce just an “average” historic performance from here the overall balanced portfolio will earn little more than 4% a year.

With so many pension plans and retirement dreams riding on returns of 7% or even 9% a year, only three things can happen.

Investors can hope for a mathematical miracle.

Or they can downgrade their expectations.

Or they can work out, somehow, to make sure that their investments…do better than the, er, average.