It’s logical that when the U.S. dollar is strong, U.S. exporters struggle — American companies have to respond either by cutting prices or by sacrificing market share.

What’s not logical is that when the U.S. dollar DXY, +0.27% is strong, foreign exporters also struggle.

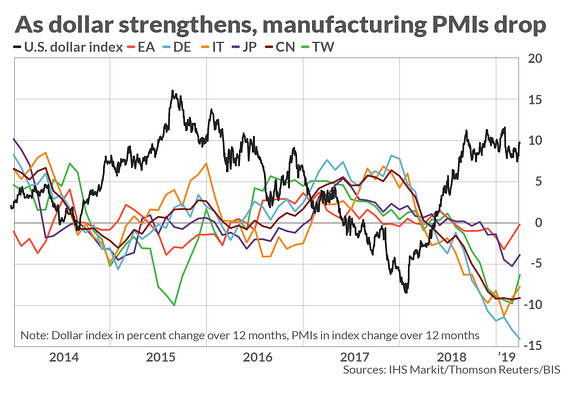

Yet that’s been the case of late. Chinese, German, Italian and Japanese manufacturing purchasing managers indexes also have been lower than year-ago levels even at a time of dollar strength, when U.S. consumers and businesses can more easily afford foreign goods.

In a speech delivered in Washington, Hyun Song Shin, head of research for the Bank of International Settlements, pointed out that banks supply financing for working capital predominately in dollars.

So for emerging economies in particular, a higher dollar is associated with tighter funding conditions.

“Long and intricate [global value chains] mean that there are many balls in the air at the same time, signifying the need for greater financial resources to knit the production process together. Looser financing conditions are like weaker gravity for the juggler,” Shin writes.

“When financing conditions are loose, the firm juggling so many balls in the air finds that it can throw more balls up at the same time and manage to keep them there at little financial cost. But when financial conditions tighten, it is more difficult to keep so many balls in the air at the same time. The large balls become especially heavy.”

A related point was made in 2015 by Gina Gopinath, who then was a Harvard professor and now is the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund. She pointed out that the overwhelming share of world trade is invoiced in very few currencies — mostly, the dollar — and that international prices are not sensitive to exchange rates.

Shin’s point is that the accounting basis for macroeconomics is looking “creaky” at a time of multinational firms and global value chains. He said the caricature of the global economy as a collection of islands — e.g. where a weak currency boosts one island’s exports until a trade balance is restored — is misleading. Corporate savings has been an important determinant of current account balances, and many countries are showing gaps between exports measured in balance of payments and exports measured in customs data.

Citing a past BIS report, Shin noted how around 90% of advanced-economy trade was accounted for by multinational companies, and around 50% was within-firm trade — that is, trade between affiliates of the same company.