(Bloomberg) — China’s tech industry enters a new year after weathering unprecedented turbulence in 2019, when giants emerged in social media and artificial intelligence only to bear the brunt of Washington’s campaign to contain the world’s No. 2 economy. There’s little reason to think 2020 will be much different given U.S. efforts to hobble Chinese champions from Huawei Technologies Co. to SenseTime Group Ltd. deemed a threat to national security.

American lawmakers went after some of the country’s biggest names last year. Foremost among them were smartphone and networking titan Huawei and ByteDance Inc., the Chinese wunderkind that in the span of a few years overturned social media entertainment and drew a billion-plus mostly younger U.S. users to its online video app TikTok. The heightened scrutiny came just as pressure back home intensified.

Beijing sought to scrub sensitive content from ByteDance apps and Tencent Holdings Ltd.’s WeChat, while the economy grew at its slowest pace in decades, depressing Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.’s e-commerce business. Investors cooled on the sector with venture capital activity halving — triggering fears the industry’s heyday is over. That in turn demoralized the country’s already-overworked tech professionals, who rebelled for the first time against the 70-plus hour workweeks that Alibaba-founder Jack Ma labeled the norm.

Given Washington’s increasing hostility, China is now even more driven to devise alternatives to foreign technology from AI chips to blockchain solutions while propping up local champions: bad news for the likes of Qualcomm Inc. and Apple Inc. that depend on China for much of their revenue. It’s started to upend a decades-old supply chain centered around China, threatening to split the old world order in two. It’s not just in hardware — from Russia to Southeast Asia, many governments have begun to co-opt characteristics of the Chinese internet arena, from harsh fake-news laws to censorship and data sovereignty.

“This year was perhaps the first year we understand China tech at its most global ever. But it also showed us the specter of it becoming more and more insular,” said Michael Norris, research and strategy manager at Shanghai-based consultancy AgencyChina. “This is bigger than just the U.S. in terms of about assuaging the fears of countries like India that platforms aren’t going to disseminate nude photographs or hate speech.”

Here’s what happened:

A Capital Winter

The industry’s woes may be best quantified by a plunge in capital flow. The amount of venture money invested plummeted by more than 50% to about $50 billion from a record $112 billion in 2018, when it topped the U.S., according to the market research firm Preqin. VC funding dropped in the U.S. too, but only slightly. China birthed only 15 unicorns, or startups worth at least $1 billion, down from 35 the year before, according to CB Insights.

The plummet coincided with a loss of confidence in some of the industry’s marquee names, exemplified by the rocky debuts of WeWork and Uber Technologies Inc. While Alibaba raised $13 billion in a milestone Hong Kong offering, smaller names like SenseTime and Full Truck Alliance struggled to raise capital. “The power of the mobile revolution is coming to an end. Globally, we are seeking what comes next,” said Kai-Fu Lee, founder of Sinovation Ventures.

The startup and VC industry is likely headed for a shakeout. Many investments from the past bubbly years aren’t panning out, with startups struggling to live up to their valuations. Fundraising by China-focused venture firms fell by about 50% to about $13 billion, according to Preqin.

James Hull, a Beijing-based analyst and portfolio manager, said there’s a sense that the “easy stuff” in China’s internet startup scene is done. Hull expects the next hot wave might be the enterprise sector. “But I don’t think that will play out as well because B2B is difficult — the selling is difficult.”

Huawei: Down But Not Out

The year kicked off with Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou under home arrest in Vancouver, fighting extradition to the U.S. Then the Trump administration tightened its grip on China’s largest tech company in May, banning Huawei from buying some components and software from American tech giants including Intel Corp. and Google. Throughout 2019, Washington pushed allies to pass on purchasing Huawei-made fifth-generation telecom gear, accusing the company of aiding Chinese espionage. Huawei’s disputed such claims but that didn’t stop Japan, Australia and New Zealand from blocking Huawei from 5G projects.

The most immediate repercussions lie with its smartphone business. New Huawei models introduced on overseas markets will be devoid of must-have Android apps like Google Maps and Gmail. In response, Huawei stepped up efforts to become more self-reliant, mobilizing its 190,000 employees to develop in-house alternatives and unveiling a potential Android surrogate dubbed Harmony OS.

The tumult forced reclusive Huawei billionaire founder Ren Zhengfei into the media spotlight to defend his company, lash out at the U.S. and expound on his company’s efforts to lead the coming 5G revolution. Huawei may have survived the first wave but it’s likely that the real pain will come in 2020.

Stars Are Born

China’s tech boom over the past decade birthed twin giants Alibaba and Tencent, a duo that effectively controls almost every aspect of the country’s internet through their sprawling business empires and vast investment portfolios. But from 2019, a new generation of tech darlings rose to the fore and now challenge their forebears.

Foremost among them is ByteDance, the world’s most valuable startup. After its first breakout hit, news app Toutiao, the Chinese company is rocking youths the world over with TikTok, an app known for everything from teenage twerking to singing gummy bears. It’s been downloaded about 1.45 billion times since launching, but has become a lightning rod for criticism as tensions rise between the U.S and China. From Facebook Inc. chief Mark Zuckerberg to a growing coterie of lawmakers, prominent Americans warn that user data may wind up in Chinese government hands. ByteDance has repeatedly denied that could happen.

The year will see ByteDance try to extend its tentacles into a panoply of fields. It’s testing a paid music app in emerging markets to challenge the likes of Apple Music and Spotify. It’s looking to make video games to tackle Tencent on its home turf. Other rising contenders include Tencent-backed super app Meituan and AI leader SenseTime.

Meituan, which displaced Baidu Inc. as China’s third most valuable tech firm last year, will continue to battle Alibaba in nascent areas from food delivery to online travel. For SenseTime and fellow domestic AI pioneers such as Megvii Technology Ltd., the challenge will be grappling with U.S. sanctions that threaten to crimp their fledgling businesses.

Dismantling the Old World Order

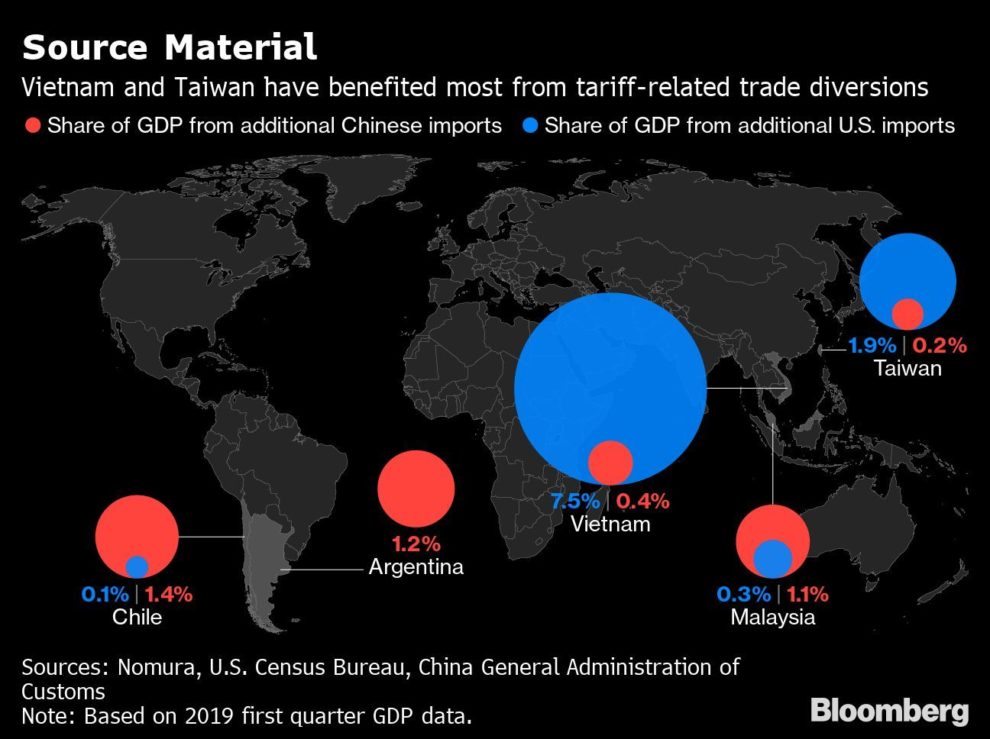

China’s position as factory for the world of technology is in jeopardy. The (mainly Taiwanese) assemblers of the world’s electronics are exploring options beyond China to varying degrees. From Inventec Corp. to Foxconn Technology Group and Quanta Computer Inc., the makers of everything from iPhones to Dell laptops have either moved production back to Taiwan or to further-flung regions around Asia, seeking to escape U.S. tariffs. The idea is that, even if Washington and Beijing strike a trade deal, diversification is essential in the longer term given tensions are unlikely to subside and labor costs will rise.

Even leading Chinese hardware suppliers recognize the risks. Luxshare Precision Industry Co. has invested in Vietnam and established a unit in India, while Goertek Inc. has begun making Apple’s popular AirPods earbuds in Vietnam. Taken together, the collective exodus spells the start of the end of a system that’s served the world’s leading electronics brands well since the 1980s.

Workers’ Woes Mount

Last year forced Chinese tech workers to come to terms with the new reality. Many had taken jobs with startups in the hope of cashing in when they debut or get bought. But as that deal-making streak cooled, the prospect of working long hours — 996, or 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week — lost much of its appeal. In March, Chinese programmers on GitHub put together a list of companies known for short-changing their employees on overtime. That post spurred a greater awareness of the human cost of China’s tech boom. In December, Huawei drew widespread condemnation when a former employee who had been detained for 251 days after the company reported him to police for alleged extortion was released without charge.

One thing’s clear: the Chinese tech arena, long regarded as an alternate reality to a U.S. app-dominated world, will draw further away from its American counterpart. And some of its biggest players will seek to extend their influence overseas, as they’ve done from Africa to Southeast Asia.

“What’s changed is the trade war, the talk of decoupling,” said Paul Triolo, head of global technology policy at Eurasia Group. “This has really galvanized the authorities. It doesn’t necessarily mean that they will be more successful. But they’re determined.”

–With assistance from Edwin Chan and Lulu Yilun Chen.

To contact the reporters on this story: Colum Murphy in Beijing at [email protected];Gao Yuan in Beijing at [email protected];Debby Wu in Taipei at [email protected];Zheping Huang in Hong Kong at [email protected]

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Peter Elstrom at [email protected], Edwin Chan, Colum Murphy

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com” data-reactid=”78″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.