(Bloomberg Opinion) — College textbooks can be expensive! The list price for the hardcover print version of N. Gregory Mankiw’s “Principles of Economics,” which I am singling out for reasons that will become apparent later, is $249.95.

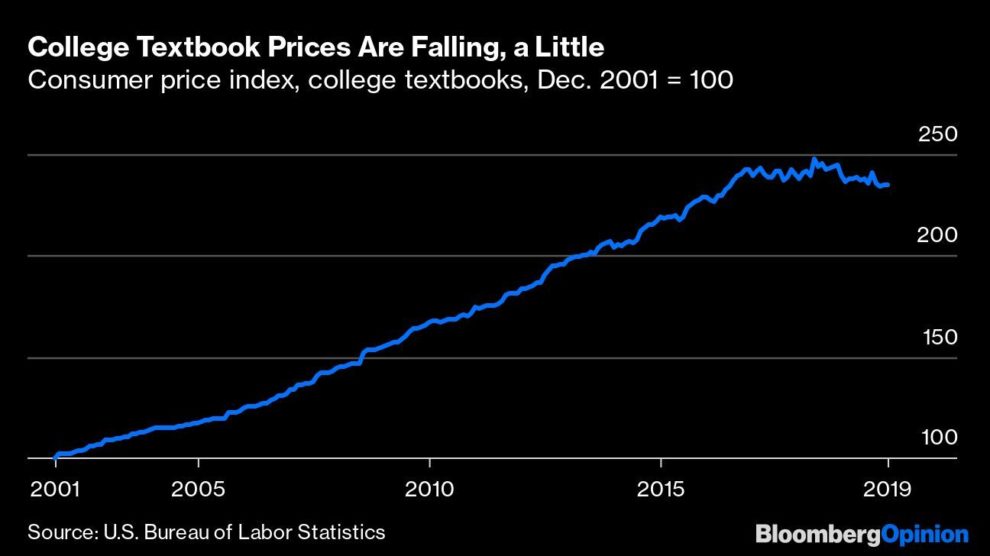

Textbooks have also gotten a lot more expensive over the past few decades. Prices of college textbooks are up 135% since 2001, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics began keeping track, while the overall consumer price index is up 46% and what the BLS calls “recreational books” have actually gotten a little cheaper. In the broader category of educational books and supplies, for which the BLS has price data going back to 1967, prices started rising faster than inflation in 1981 and are up almost ninefold since.

This price explosion has gotten lots and lots of attention in the news media and in academia. What has gotten somewhat less attention is that, as you may be able to see in the above chart, it seems to have ended in 2016. Here’s the chart since 2001 just for college textbooks, which makes that even clearer.

Economist and inveterate chart-maker Mark J. Perry of the University of Michigan at Flint and the American Enterprise Institute was among the first to pick up on this, in 2017. He speculated that the causes included the rise of new sales and rental channels, digital offerings from established publishers, and competition from newcomers such as the for-profit FlatWorld and the nonprofit OpenStax.

That … sounds about right. Used-textbook sales started growing in the late 1990s thanks to eBay and Amazon.com, according to a 2014 analysis by the consulting firm McKinsey. Textbook-rental services “emerged as a mainstream option” in 2008 and rapidly gained market share. Established publishers reacted by accelerating the move to digital course materials that they effectively rent to students, usually at lower upfront cost than a textbook. But others are now providing similar offerings free: OpenStax, based at Rice University in Houston, estimates that 2.9 million students used its free digital textbooks last year. Other university-backed free-textbook efforts include the University of Minnesota’s Open Textbook Library and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Open Courseware project.

The National Association of College Stores’ most recent survey of student spending found that 44% of U.S. and Canadian college students rented course materials in spring 2019, while 22% downloaded free course materials — double the share who reported doing so in 2016. The survey also found that average annual student spending on textbooks and other course materials is down 31% since the 2015-2016 academic year, and 41% since 2007-2008.

A different survey, by the research firm Student Monitor, found a similar decline. Textbook publishers have definitely been feeling the impact, as is clear from Pearson Plc’s stock performance since it sold off the Financial Times and the Economist in the summer of 2015 to focus on what Chief Executive Officer John Fallon predicted would be “one of the great global growth stories of the next decade.” (I use the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index as the standard of comparison here because, although it’s a British company, Pearson gets more than 60% of its revenue from the U.S.)

In the U.S. market for new college course materials, Pearson had a 42.7% share in 2018, Cengage 21.8% and McGraw-Hill Education 15.9%, according to research firm Simba Information. That’s their share of revenue, and thus doesn’t reflect the inroads made by free textbooks. The fact that all three saw significant declines in college-course-materials revenue in 2018 (6.5% for Pearson, 5.8% for Cengage and 8.5% for McGraw-Hill, estimates Simba) presumably does reflect those inroads.

Cengage and McGraw-Hill are both owned by private-equity firms, which is why they’re not included in the above stock chart. They are also in the midst of consummating a merger, which is opposed by various organizations that say this will give them the leverage to jack up prices. A market of which the top two players control a combined 80% would in fact be quite concentrated, but given that publishers are struggling and prices falling, is this really something to worry about?

The answer depends on how durable you think the challengers to the publishers’ business model are. The resale and rental markets seem doomed as textbook delivery shifts to digital, which leaves mainly the university-backed free-digital-textbook providers. The aforementioned Greg Mankiw, a Harvard professor whose textbook has been the introductory-economics market leader for quite a while, professes to be skeptical of their staying power. “The current for-profit educational publishers are not that profitable,” he wrote in an essay last year, “and there is no reason to think that a non-profit entity would find cost savings that have eluded existing publishers.”

He has a point about the profitability. Even before the textbook-rental services started making inroads, the major textbook publishers usually had operating-profit margins in the single digits. Textbook prices would appear to have gone up not so much because of price gouging but because producing them has gotten more expensive, a trend exacerbated on a per-copy basis by the downward pressure used copies and rentals have exerted on new-textbook sales. Given that the prices of other books have fallen, though, one does suspect that textbook publishers have chosen especially inefficient and costly ways to go about their business. If frequent updates and revisions, colorful graphics and other gewgaws are of limited educational value, maybe there is a place for nonprofit publishers that dispense with the frills. The open-textbook movement has mainly focused on introductory texts, where such an approach makes the most sense.

The for-profit publishers have been reacting by offering add-on services and encouraging students to subscribe rather than buy. For example, U.S. students can access Mankiw’s “Principles of Economics” by paying $130 for six months of MindTap for Principles of Economics, which includes an online text of the book plus an array of learning tools, or $119.99 for a four-month subscription to Cengage Unlimited that includes MindTap. They can also pay $328.95 for a print copy of the book plus six months of MindTap, or $34.49 for a bare-bones four-month ebook rental.

This approach seems to be working. Pearson reported last month that “underlying revenue” held steady in 2019 for the first time since 2014, with CEO Fallon — who will be leaving later this year — telling analysts and investors in a call that the shift to digital, while it has been “challenging,” was finally starting to pay off:

For Pearson, longer term, it means a more sustainable business as we build direct relationships with 10 million plus learners who pay us directly to use our products.

It’s those “direct relationships” with students that have some in higher education most worried. “They have direct access to student wallets,” says Nicole Allen, director of open education at the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition. “What could go wrong?” Sparc, which counts more than 200 colleges and universities as members, is one of the groups fighting the merger of Cengage and McGraw-Hill, and Allen has been urging member institutions to make sure the contracts they sign with publishers limit the ability “to gather and control data on students.” Also key to avoiding overdependence on publishers, she says, is the ability of universities to build and maintain an alternative, open(ish) infrastructure for course materials.

A lot of the early open-textbook efforts have been funded by foundation grants, which tends not to be a sustainable model. Rice’s OpenStax, founded by professor of electrical and computer engineering Richard Baraniuk, has started generating revenue by licensing its free textbooks to for-profit publishers to be included in their courseware platforms, while also developing a rival platform for which it charges $10 per student per course. “History shows that when you have an open, freewheeling ecosystem, innovation happens faster and things become more efficient,” Baraniuk told education-tech publication EdSurge last year.

That sounds encouraging. But it’s also worth noting that American universities don’t exactly have a great track record of keeping costs down for students. Remember that statistic about the prices of educational books and supplies rising ninefold since 1981? Average undergraduate tuition and fees at U.S. colleges and universities are up almost tenfold since then.

To contact the author of this story: Justin Fox at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stacey Shick at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”69″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.” data-reactid=”70″>Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.