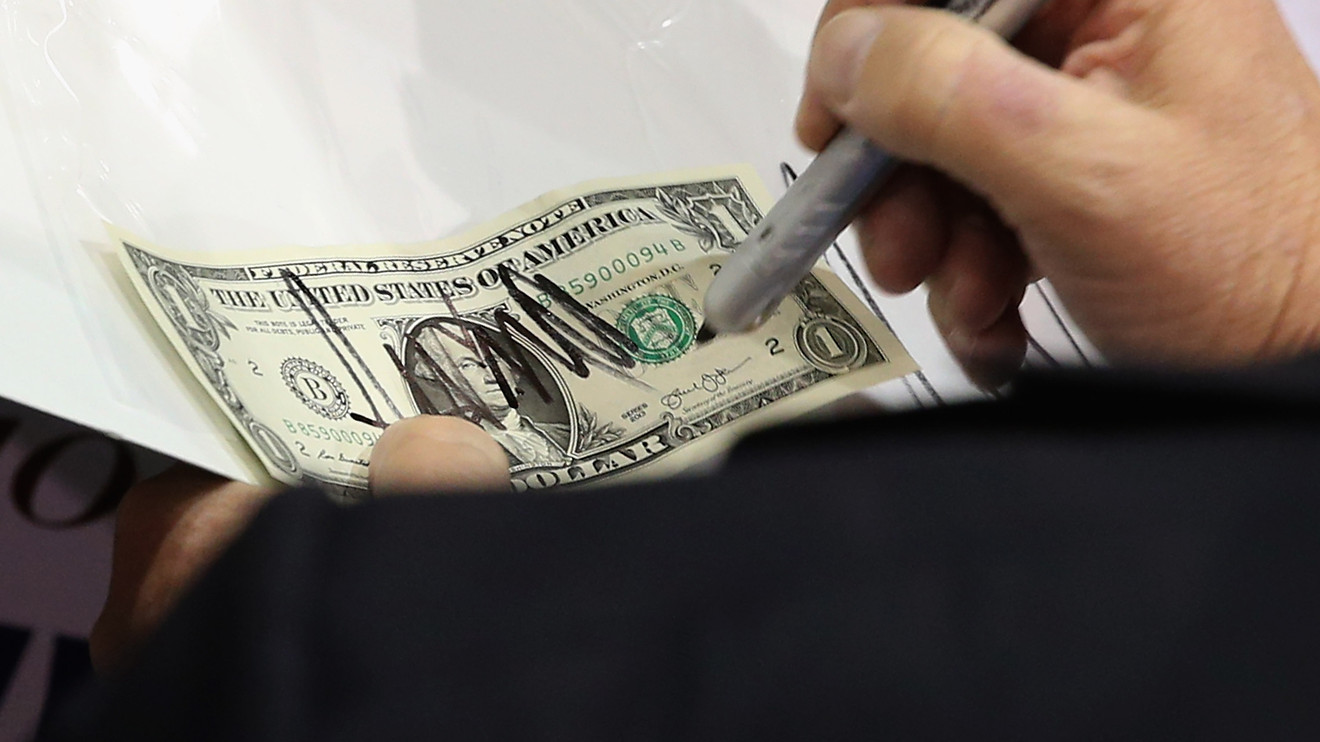

President Donald Trump’s latest Twitter attack on Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on Friday, accompanied with more complaints about the strength of the U.S. dollar, is stoking long-running fears the administration could break with decades-long orthodoxy to intervene in currency markets.

“On the back of his blistering outburst, the market is speculating whether Trump will take direct action to weaken the greenback,” said Jane Foley, senior foreign exchange strategist at Rabobank, in a note.

Despite an assurance from White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow earlier this summer that currency intervention had been ruled out, Trump’s repeated complaints about the dollar’s value relative to other currencies has underlined concerns that the administration could attempt a move to lower its value.

Trump’s latest blast, which came after Powell delivered an eagerly awaited speech at the Kansas City Fed’s annual symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, was part of a series of tweets in which Trump also responded to China’s announcement that it would impose retaliatory tariffs on $75 billion worth of U.S. goods beginning in September and December. Trump prompted confusion when he also tweeted that he had “hereby ordered” U.S. companies to begin looking to alternatives to China.

The remarks were also blamed for a steep stock-market selloff, that saw stocks tumble, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -2.37% declining more than 600 points to end the day down 2.4%, while the S&P 500 SPX, -2.59% shed 2.6%.

The ICE U.S. Dollar Index DXY, -0.92% , a measure of the currency against a basket of six major rivals, was down 0.5% at 97.722. The euro EURUSD, +0.5685% rose 0.5% to $1.1135, while the dollar fell 0.9% against the Japanese yen USDJPY, -1.00%, a traditional haven during market turmoil, to trade at ¥105.45.

Concerns about the toll of an intensifying trade war on China’s already slowing economy saw the yuan weaken, sliding to 7.1334 per dollar in offshore trade USDCNH, +0.6432%. China earlier this month failed to halt a fall in the yuan USDCNY, +0.1736% that saw the currency trade above 7 per dollar for the first time in more than a decade, a move that saw the U.S. paradoxically decide to formally label China a currency manipulator.

The U.S. dollar has indeed been strong, with the ICE index up 1.6% in the year to date, while a trade-weighted measure of the currency is near an all-time high. Expectations for the European Central Bank to further cut interest rates into negative territory and potentially unveil other stimulus measures as early as next month have contributed to euro weakness, with the shared currency off 2.8% in the year to date.

Economists and analysts question the potential effectiveness of unilateral intervention against a global backdrop that appears to favor dollar strength, given U.S. Treasury yields offer a higher return than other country debt, the strength of the U.S. economy, and the U.S. dollar’s status as a safe haven reserve currency used in a majority of international trade and investment transactions.

A decision to intervene “would mark a significant change in policy for the U.S. Treasury and would undoubtedly be met with significant criticism from other G7 nations,” Foley said. “In the absence of Treasury intervention it is our view that the USD is primed to remain firm in the coming months on the back of strong demand triggered by risk aversion and linked to trade tensions and the slowdown in global growth.”

Indeed, U.S. intervention could itself backfire, serving to further strengthen the currency after any initial downside reaction, said Steve Barrow, head of G-10 strategy at Standard Bank, in a Friday note.

That’s because the dynamic in global markets since the financial crisis has increasingly reflected a desire for safe assets, Barrow said, noting arguments that the dollar has become more inversely correlated with U.S. purchases of foreign bonds since the crisis. Under this theory, the dollar’s rise for the most part since the crisis reflects high risk in emerging markets and U.S. reticence to buy foreign debt on par with what was seen before 2008, he said.

If the dollar’s value is, in fact, an inverse reflection of risk appetite, it suggests U.S. intervention would be counterproductive, he wrote, since it would raise global risk aversion significantly and likely be viewed as an extension of the trade war.

Moreover, intervention would be unlikely to be joined by other central banks and would go against the Group of 20’s commitment not to engage in such endeavors.

“The bottom line in our view is that past interventions have not been associated with the sort of spike in risk aversion that would surely follow any U.S. dollar sales by the US Treasury now, or in the foreseeable future,” he said. “Add this to the greater sensitivity of the dollar to changes in risk aversion and it looks to us that intervention would be a monumental failure.”