(Bloomberg Opinion) — No, value investing is not dead.

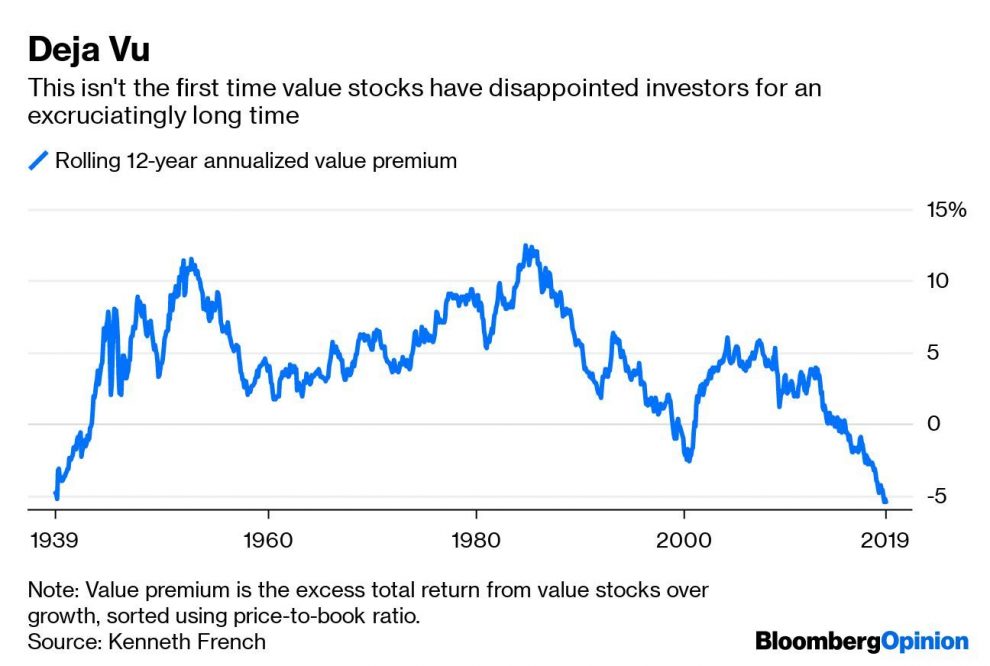

I’ve lost count of the recent articles and blog posts asking whether it’s time to toss value in the dustbin of investing strategies. The question was inevitable. Value stocks in the U.S. have lagged growth since early 2007, a brutal and rare 12-year stretch of underperformance. Over the last nine decades, the longest period for which numbers are available, value has fallen behind growth for this long just twice before, during the Great Depression in the 1930s and the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s.

Value’s latest disappearance is causing more than just value investors to scratch their heads. There’s been widespread agreement among academics and practitioners for decades that investors can expect value stocks to outpace growth over time. This “value premium” is supported by both evidence and intuition. Value stocks are dominated by companies, and often sectors, whose growth has slowed or stalled, so their prospects are less rosy and more uncertain than those of growth companies. Befitting their humble state, value stocks sell at a discount to growth. After all, who would buy sleepy banks and energy firms such as Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Chevron Corp. and Exxon Mobil Corp. if they cost the same as highfliers such as Amazon.com Inc., Facebook Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Google parent Alphabet Inc.?

That discount has historically given value stocks a boost, as might be expected. The cheapest 30% of U.S. stocks, based on price-to-book ratio and weighted by market value, outpaced the most expensive 30% by 3 percentage points a year from July 1926 through May, including dividends, according to data compiled by Dartmouth professor Ken French. Value has also beaten growth 69% of the time over rolling three-year periods, counted monthly, 74% over five years, 83% over 10 years and 87% over 12 years. The results are similar using other measures of value, such as price-to-earnings ratio and price-to-cash flow ratio.

Those numbers may come as a surprise to a generation of investors for whom value investing is synonymous with disappointment. Value stocks as measured by P/B ratio trailed growth by a crushing 5.5 percentage points a year from April 2007 through May. Other measures of value fared better but also fell behind. Using P/E ratio and P/CF ratio, value lagged growth by 2.1 percentage points and 2.6 percentage points a year, respectively, over the same period.

As value’s history shows, there’s nothing new about its latest disappearance. The value premium vanishes occasionally, and sometimes for long periods, before reappearing. But past isn’t necessarily prologue, and the longer value languishes, the more investors question whether history is still a reliable guide.

There are already some popular theories as to why the value premium may be gone for good, but none are particularly appealing. One is that value investing has become too popular. Once the value premium was discovered, the theory goes, investors piled into value stocks and squeezed the premium away. But no matter how popular value becomes, value stocks will always be cheaper than growth by definition. If popularity is killing value, one would expect the premium to shrink, or even disappear, rather than turn sharply negative, as it has in recent years.

Also, if value’s popularity is growing, its discount relative to growth should be shrinking, but the opposite is happening. The P/B ratio of growth stocks was six times that of value in 2018 — and it’s almost certainly higher today after another miserable year for value — compared with four times in 2007. In fact, growth has only been more expensive relative to value twice. You guessed it: during the Great Depression and the dot-com bubble. P/E ratios and P/CF ratios tell the same story.

A second theory is that growth companies are more dominant than they used to be. Their vast technological edge and near-monopolistic powers, it is said, will allow them to outpace value companies for the foreseeable future. If that were true, the market value of growth stocks would be expected to increase relative to value, but here again, just the opposite has happened. The top 10 stocks in the S&P 500 Growth Index account for 17.3% of the S&P 500 Index, down from 18.7% in 2009 and 20.9% in 2001, the first year for which numbers are available.

A third theory — and the most generous to value — is that the measure of value is broken, not necessarily the strategy itself. P/B ratio is widely used by researchers and indexes to identify value stocks, but some complain that book value no longer captures the full value of intellectual capital and other intangible assets of fast-growing companies such Amazon, Google and Facebook, making them appear more expensive than they truly are.

While it’s true that P/B ratio has been the worst-performing measure of value over the last 12 years, it’s premature to call it obsolete. No one measure has performed consistently better than others in decades past, so it’s just as likely that P/B ratio’s recent struggles are purely coincidental. There were similar concerns about book value during the dot-com bubble, and P/B ratio performed as well or better than other measures.

Also, P/B ratio has a long history of strong performance relative to growth stocks following bouts of weak performance, and vice versa, which strongly suggests that its recent underperformance will prove to be cyclical rather than permanent. After the Great Depression, it delivered a value premium of more than 10% a year during the 1940s. And after the dot-com bubble, it delivered a premium upward of 7% a year.

Sure, this time may be different. But every time an investing strategy is out of favor for an unbearably long period, a chorus rises to warn that things have changed — and it rarely pans out. Remember the famous BusinessWeek cover declaring “The Death of Equities” in 1979, after a miserable decade for U.S. stocks and just before the start of a two-decade bull market? Or all the carping about washed up value investors during the dot-com bubble? Financial history is littered with similarly earnest but ultimately misguided prognostications.

Of course, investors can sidestep the value versus growth debate by simply buying the market. But with value boasting its historical dominance and growth insisting that the world has changed, don’t count out value.

To contact the author of this story: Nir Kaissar at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”66″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.