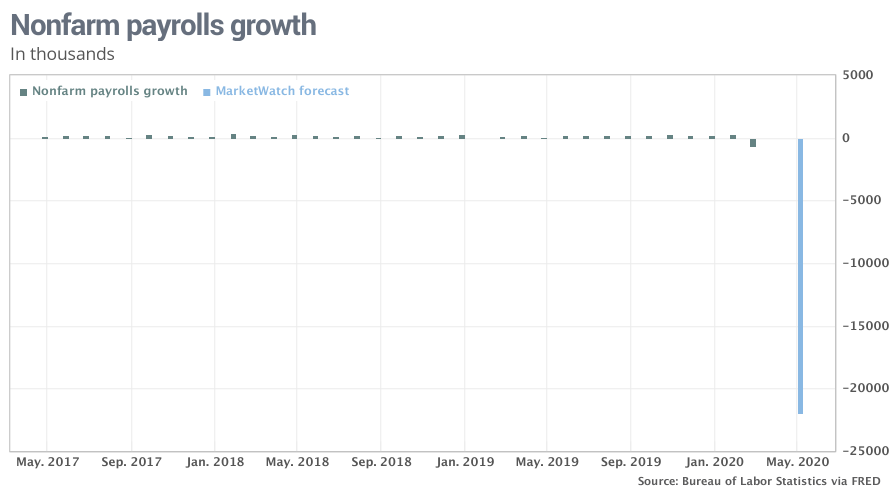

The United States appears to have lost more than 20 million jobs in April, but even such a shockingly large increase might understate the destruction wrought by the coronavirus on the labor market.

The large payroll processor ADP on Wednesday reported a 20.2 million decline in employment in April among the nation’s privately run companies. Small businesses, hotels, restaurants and retailers were especially hard hit.

Read:ADP says 20.2 million private-sector jobs lost in April during coronavirus pandemic

The government is expected to report a similarly large wipeout on Friday with the official employment report for April.

Economists polled by MarketWatch predict 22 million jobs were eliminated last month, at least temporarily. And the unemployment rate is seen rocketing up to 15% from a 50-year low of only 3.5% two months ago.

Yet whether the government gets the numbers right, or is even close, probably won’t be known until well after the crisis has passed and experts can dig deeper.

A separate report that counts the number of people who’ve applied for unemployment benefits has already topped a record 30 million in six weeks, and an additional 3 million likely filed new jobless claims last week, the MarketWatch survey shows.

Read:The unemployment checks still aren’t in the mail for millions of jobless workers

Not all of the people who sought benefits are necessarily out of work. An untold number — potentially adding up to several million — have returned to their jobs and more are going to get the call, particularly in states such as Georgia, Florida and Texas that are slowly reopening.

Still others have been added back to their company payrolls even though they are not working. Washington has approved almost $3 trillion in federal aid to help stabilize the economy, including a special program for small businesses that offers forgivable loans if they keep paying idled employees.

The unemployment rate, for its part, might not reflect the true damage to the labor market because of how it’s calculated.

Millions of Americans who work in industries such as retail, for example, have been furloughed without pay. They are collecting unemployment benefits while they wait to be recalled from their furlough and aren’t actively looking for work as is typically required.

Normally they would be classified by government bean-counters as having dropped out of the labor force and thus not be included in the unemployment rate, making it look artificially lower.

Some economists contend the Labor Department will adjust their formula and accurately count them as unemployed and part of the labor force. If they do, chief economist Chris Low of FHF Financial, predicts the unemployment rate could surge to as high as 22%.

That’s not far off from the all-time high of 25% during the Great Depression in the 1930s. The economy was much different then, but the magnitude of unemployment then and now merely punctuates how badly the economy has deteriorated.

A more accurate picture of the stress on the labor market might be visible in another measure used by the government known as the U6 unemployment rate, economists say. That rate includes discouraged job seekers, those forced to work part-time and other people on the fringes of the labor market.

The U6 rate could soar to as high as 30% from less than 7% before the crisis.

Another oddity that’s likely to show up in the April employment report is a surge in wage growth. The pandemic and resulting shutdown of much of the economy has been especially devastating to workers in lower-paying industries such as leisure, hospitality and retail. Higher earners have been less harmed.

“Average hourly earnings are likely to rise sharply, but this is only because low-wage workers are bearing the brunt of the job losses,” economists at Credit Suisse wrote to clients in a note.

Read: Why the U.S. economy’s recovery from the coronavirus is likely to be long and painful

All the estimates, in any case, should be taken with a grain of salt.

There’s no question the labor market and the economy as a whole is going through its worst crisis in almost a century and no number can fully capture that reality. Many companies have already closed or gone out of business, making it even harder for the government to tally up the damage in real time.

“None of us has any reasonable way of forecasting ‘the’ number given all of the variables in play,” acknowledged chief economist Richard Moody of Regions Financial.