(Bloomberg Opinion) — The European Commission is largely happy with the first year of its sweeping digital privacy rules. Evidence mounts, however, that the General Data Protection Directive, or GDPR, as applied today hurts smaller firms and has no effect on tech giants, which are the least interested in preserving user privacy.

The directive went into effect in May 2018, demanding companies provide privacy by design and by default on all digital platforms and websites. It laid down the rules for collecting and processing private data, including the cases in which consent is necessary for their harvesting. This week, the commission put out an optimistic progress report, describing the GDPR’s first year as “overall positive” and suggesting a number of mild improvements in applying it.

The report said, among other things, that the national privacy watchdogs tasked with enforcing the GDPR had “focused on dialogue rather than sanctions, in particular for the smallest operators which do not process personal data as a core activity.” This explains why there are few examples of anyone being fined for noncompliance, though, according to the directive, sanctions can be quite severe – up to 4% of global annual sales.

The fines that actually have been imposed range from 5,000 euros ($5,558) on a sports-betting cafe in Austria for illegal video surveillance to 50 million euros on Google in France for the opaque process of signing in for a Google account, all but necessary to use an Android smartphone. In between, there are some penalties of hundreds of thousands of euros, such as 220,000 for a Polish data broker that failed to inform people that their data was being processed. Altogether, authorities in the entire European Economic Area (which includes the EU member-states plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein) have imposed just 56 million euros worth of fines.

But 50 million euros is not even a mosquito bite for Google, and other tech companies — most notably that other greedy data harvester, Facebook Inc – haven’t been taken to task at all. This despite many well-grounded complaints filed against some of them by activists, most notably the Austrian lawyer Max Schrems’ noyb (None of Your Business) initiative, which was also behind the successful complaint against Google in France. Indeed, it was a U.S. regulator, not a European one, that slapped a $5 billion penalty on Facebook for privacy violations this week – even though the U.S. lacks a comprehensive regulatory framework like the GDPR.

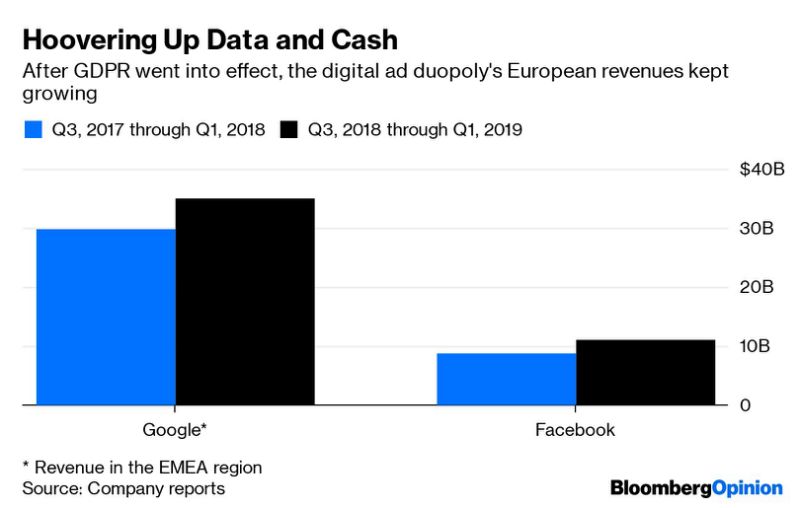

It’s hard to quantify the exact impact of the GDPR on the internet giants, but they haven’t stopped growing in Europe.

That, however, can’t be said of many smaller digital businesses. According to a recent paper by Samuel Goldberg from Northwestern University, Garrett Johnson from Boston University and Scott Shriver from the University of Colorado, these have seen 10% lower European page views and revenues since the GDPR went into effect. Among e-commerce sites, revenue dropped by 8.3%, or $8,000 a week for the median site. The economists used data from the Adobe Analytics platform, tracking the traffic and sales of 1,500 firms from various industries, which generate a total of about $500 million in weekly revenues.

The losses likely weren’t driven by more privacy awareness among users: More than 90% of them consent to the collection and processing of their data when prompted to do so. Rather, the GDPR deterred companies from using email and display ads to drive traffic, because these methods require the use of personal data; it has also reduced the number of third-party cookies on websites, making it more difficult to track consumer behavior.

The data analyzed by Goldberg and collaborators aren’t the first indication that the privacy regime has hurt the smaller digital players. Last year, another group of researchers found that venture funding for European tech firms dropped off after the directive came into effect. One possible reason is that the increased compliance costs and reduced marketing opportunities have adversely affected European startups’ business models and made them less competitive with peers in other parts of the world.

The contrast between the GDPR’s hard-to-detect impact on the biggest data harvesters, whose compliance is reluctant and largely nominal, and its demonstrated adverse effect on smaller companies makes it difficult to understand why the European Commission finds the first-year experience positive.

The national data privacy authorities are ill-equipped to deal with the giants. Before the GDPR came into effect, most of them asked for 30% to 50% funding increases but none received that much; in fact, two of the national watchdogs saw their funding cut and three others didn’t receive any extra money. With their inadequate resources, they had to handle more than 200,000 GDPR cases. Big Tech’s expensive legal teams can run circles around such overstretched opposition.

To be fair, the EU progress report does call for strengthening the watchdogs. But without big rulings, political justification for the extra spending will be hard to come by.

The GDPR can only serve Europeans’ privacy needs if there’s a level playing field for the giants and the smaller companies. That means imposing similar costs relative to their size. That’s not the case now, and the European Commission doesn’t appear to see it as a problem. This makes the privacy rules much less of a shining example to the rest of the world than they could have been.

To contact the author of this story: Leonid Bershidsky at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tobin Harshaw at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion’s Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”43″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.