Bullish investors are paying little attention nowadays to a big stock-market negative — as in negative real interest rates.

Because of this situation, the odds are disturbingly high that U.S. stocks over the next five years will barely beat inflation. Just don’t tell that to investors who are excited about the stock market’s impressive recovery from its waterfall decline in February and March.

But ignoring those odds doesn’t make them go away, as I was reminded recently listening to a seminar conducted by Elroy Dimson, a professor at Cambridge University’s Judge Business School and chairman of its Centre for Endowment Management. Dimson is the co-author (with Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton of the London Business School) of what most researchers accept as the most comprehensive global database of stock and bond returns. It encompasses 23 different countries and dates back to 1900.

Notably, this database also includes data on each country’s inflation, which enables a calculation for what interest rates have been on an after-inflation, or real, basis. That’s crucial, since real rates around the world right now are largely negative — in some cases at or near the lowest since 1900.

Take the current yield on the Treasury’s 10-year TIPS: minus 0.57%. This yield represents the real interest rate, since it is how much investors are willing to earn above (or below) the inflation rate. This low real yield is not a record low in U.S. history, but close.

Read: The ‘Single Greatest Predictor of Future Stock Market Returns’ has a message for us from 2030

More: The government says there’s no inflation — except for the things people are actually buying

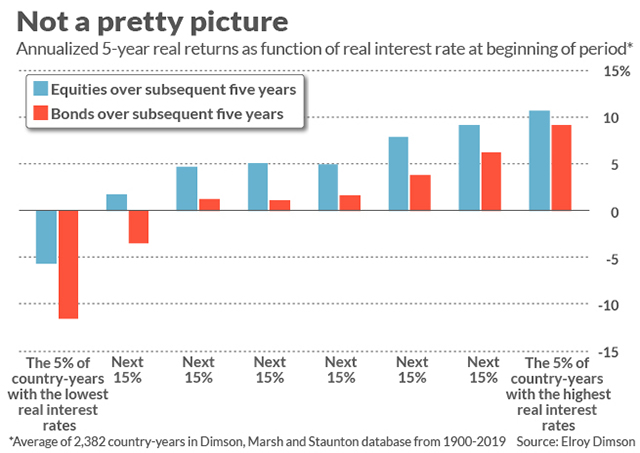

In the seminar, Dimson emphasized the strong correlation between real rates and returns over the subsequent five years for both stocks and bonds. To show that correlation, he looked at all countries and all years in his database — a total of 2,382 observations. He then segregated those observations into 8 groups: Groups 1 and 8 contained the 5% of country-years with the lowest and highest real rates, respectively. Groups 2 through 7 contained successive 15% of the observations.

As you can see from the chart below, bonds’ and stocks’ average real returns over the subsequent five years were consistently higher in countries where real interest rates at the beginning of the five-year period were themselves higher.

The chart is based on averages, so of course there are exceptions. One was the five-year period in the U.S. beginning in 2013, when real interest rates were also negative. The subsequent five years were extremely good to both stock and bond investors, needless to say.

But it’s risky to construct your investment outlook on exceptions to the rule, rather than the rule itself. And the historical correlation between real interest rates and stocks’ and bonds’ subsequent returns, while not perfect, is nevertheless quite compelling.

There’s also strong theoretical support for why this correlation would exist, according to Nicholas Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford University and co-director of the Productivity, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research. In an email, he explained that “interest rates are an excellent predictor of long-run growth potential, and their moribund level [today] reflects the markets’ expectation of sustained low future growth.”

“Until real interest rates pick up again,” Bloom noted in another email, “it is hard to be optimistic on growth — when there are great opportunities for growth in the economy firms are investing, hiring and building and rates are high. Everyone wants to borrow money. When rates are close to zero it is a terrible take on the pulse of the real economy growth is on life-support and its interest rate pulse is very weak.”

So keep all this in mind as you otherwise celebrate the Nasdaq Composite’s COMP, +0.03% recent new all-time high and the S&P 500 SPX, -0.56% and the Dow Jones Industrial DJIA, -0.80% rising to within shouting distance of theirs. Notwithstanding the impressive rally over the past 12 weeks, the prospects for both U.S. equities and bonds over the next five years appear mediocre at best.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected]