Should you dump Berkshire Hathaway stock because it’s lagging the market?

At least several longtime fans of Berkshire Chairman Warren Buffett apparently think so, as does my fellow MarketWatch columnist Howard Gold. Buffett’s transgression, at least in part: being too defensive, sitting on a large pile of cash.

Clearly, the numbers don’t look good for Berkshire Hathaway stock BRK.A, -1.06% BRK.B, -0.98% , which is down almost 25% so far this year, versus a 10.9% loss for the S&P 500 SPX, +0.39% . Moreover, last year the stock also lagged the S&P 500 by a significant margin: 11.0% to 31.2%, respectively. (These returns reflect the reinvestment of dividends.)

Read: Dud stock picks, bad industry bets, vast underperformance — it’s the end of the Warren Buffett era

Plus: Warren Buffett’s ‘outdated view’: One longtime fan is considering dumping his entire Berkshire stake

I think these skeptics are being unfair. No adviser, not even someone with as good a record as Buffett’s, makes money every year, much less beats the market. The belief that there such an adviser exists is a triumph of hope over experience. Even worse, such a belief often leads investors to prematurely get rid of excellent advisers in favor of whomever is playing a hot hand for the moment.

To be sure, there may be other reasons besides his recent performance to question whether Buffett has lost his touch. But if Berkshire’s recent performance is why you’re dismissing Berkshire Hathaway stock, you should step back and give Buffett the benefit of the doubt.

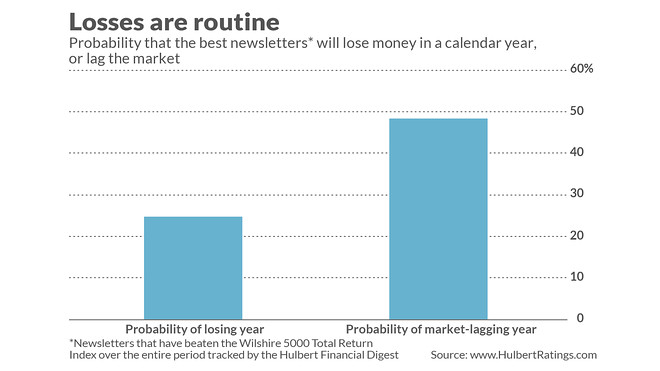

These are the conclusions I reached upon analyzing the incidence of market-lagging and money-losing years among the investment newsletter portfolios tracked by my Hulbert Financial Digest performance monitoring service. Even among those newsletters that beat the market over the entire time they have been tracked, they lose money one out of every four years, on average. And they lag a broad market index fund in an average of one out of every two years.

What are the odds?

Specifically, I calculated the odds of lagging the market in any given calendar year to be 48.3%. And the probability of actually losing money in a given calendar year is 24.7%. (See accompanying chart.) Don’t forget that these odds are for advisers who have beaten the market over the long-term.

How do Buffett’s recent returns stack up against those odds? Berkshire has lost money in none of the last 10 calendar years, for example, and lagged the S&P 500 in six of them. When compared to the probabilities that emerge from long-term market-beating advisers, Buffett’s record hardly seems so awful as to justify getting rid of him.

Another way of putting Buffett’s recent record in perspective is to explore the role of randomness in his year-to-year returns. Specifically, I conducted the following thought experiment: What if, in each of the next 10 calendar years, Berkshire’s return relative to the market (its alpha) would be picked at random from the stock’s actual past alphas over the past 55 years? And what if this experiment was repeated 10,000 times?

Notice that these simulations assume that Berkshire’s future performance is just as good as it was in the past. Even so, in a handful of them the stock lags the market in eight of the next 10 years.

To be sure, the odds of Berkshire lagging the market in 80% of the next 10 calendar years are small. But the point is that, due to nothing more sinister that sheer luck, they’re not zero.

These simulations that I ran closely mirrored ones conducted by Dartmouth professor Ken French and University of Chicago finance professor (and Nobel laureate) Eugene Fama. In a study they authored two years ago in the Financial Analysts Journal, they found that, because of luck, there is a significant probability that market-beating strategies will nevertheless lag the market over a given 10-year period.

In an interview at the time, French told me: “Statistical noise — luck in other words — is always the first possibility to consider” when judging an adviser or strategy that has lagged the market. Unfortunately, it usually is the last possibility that we consider; our instinct is to immediately conclude that the adviser has lost his touch.

Bear this in mind as you’re considering what to do with your Berkshire Hathaway stock, or with any other adviser with a good long-term record who has lagged the market recently. How confident are you that luck isn’t the culprit?

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected]

Read: Why Berkshire Hathaway stock has rarely been this cheap

More: Warren Buffett is handling the coronavirus crisis like he mastered the Great Recession