(Bloomberg Opinion) — Google and Facebook Inc. are in regulators’ sights again. Britain’s monopolies watchdog is gathering input for its “Online Platforms and the Digital Advertising Market” study.

Behind this seemingly nebulous title lies a golden opportunity to make Big Tech face some hard questions about its control over digital advertising. This could be a first, since no-one has as yet managed successfully to unpick the workings of the ad tech market. The answers could steer the conversation about a breakup of the two behemoths to their digital advertising assets, rather than their consumer-facing offerings – something that both companies would desperately like to avoid.

The Competition and Markets Authority’s investigation will span data collection, the firms’ dominant consumer-facing platforms and competition in online ads. Officials should focus their limited resources on the last of those three. Data and platform dominance feed the advertising model, and privacy is of course an important concern. But the regulator needs to follow the money.

Between them, Google and Facebook secured 56% of all global internet ad dollars in 2018, according to the World Advertising Research Council. That should rise to 61% this year.

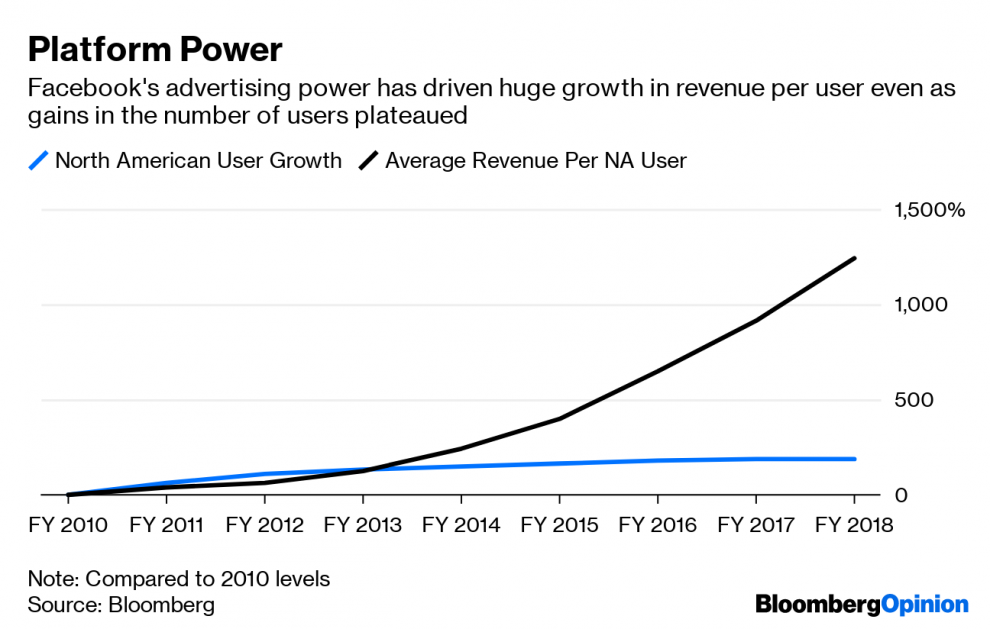

A close examination of the two firms’ earnings demonstrates how they’ve managed to consolidate their dominance. In North America, the growth in the number of active Facebook users has slowed to a crawl over the past two years. Yet the average revenue per user has continued to grow exponentially.

Meanwhile at Google, the number of impressions from its network members (i.e. websites where Google is responsible for placing the ads) also grew more slowly last year. To offset that, the cost-per-impression grew by 12%, up from 8% a year earlier.

This points towards the power both firms have to squeeze money out of advertisers. Brands can and do complain about Google and Facebook till they’re blue in the face, but if they want to advertise online they have little choice but to still send ever more ad dollars their way.

The British study explicitly cites Google and Facebook’s control over multiple important stages in the programmatic advertising process, what’s known as the “advertising stack.” That’s noteworthy. Other studies in Germany, France, Australia and elsewhere have more broadly tackled the use of data. Britain should avoid starting on a path that may just replicate their findings. Concentrating on the ad stack gets right to the heart of the firms’ business models.

The issue with the modern competitive landscape is that the distinction between the various roles in programmatic ad categories is blurring. The competition lawyer Damien Geradin, who has long been critical of Google, likens it to the sale of a painting where Sotheby’s is the auctioneer, the buyer’s agent and the seller’s agent. When you buy a painting, you tell the Sotheby’s buying agent your maximum budget is $100,000. A day later, you’re told you were the winning bidder, and paid just $75,000.

The problem is, you’ve no idea how high the next bid was. Nor does the seller know how much was offered. Maybe both got a good deal, but it’s hard to tell. You simply have to take the auction house’s word for it.

Now substitute ad views or clicks for the painting, and Google for Sotheby’s, and you get a sense of some of the problems in online advertising. Walled gardens have developed where money goes in, and results come out, but brands and publishers have little visibility on everything that happened in between.

It won’t be easy to disentangle the workings of this industry. The CMA has just 25 people dedicated staff to the study – Facebook and Google meanwhile have thousands of employees in the U.K. alone.

When Australia published the preliminary report of its Digital Platforms Inquiry in December, it admitted it was “difficult to estimate with precision whether the pricing for search or display advertising may be considered excessive.” That’s a serious problem. If the regulator, with its legal authority, can’t ascertain the truth, then brands themselves have even less of a chance.

It’s all but impossible to reach an independent evaluation of the price and effectiveness offered by the duopoly against competing platforms. Britain’s competition cops would do well to embed themselves deeply in the firms’ operations, rather than simply seeking written responses and interviews.

The CMA is accepting comments until the end of July, and in six months will decide whether to turn the study into an investigation. At the end of the study phase, the regulator can only make recommendations to lawmakers. An investigation would allow it to seek remedies to fix what it might deem an imbalanced situation. And Britain has clout. It’s likely Facebook and Google’s biggest market in Europe: the U.K. digital ads market is almost three times as big as France’s.

There are already heavy hints about what remedies might entail. The CMA’s announcement at the start of this month went so far as to moot “the separation between certain activities in the digital advertising value chain.” That might be a more astute way to tackle Google and Facebook, than, for instance, making them hive off YouTube or WhatsApp respectively.

If the CMA has the same difficulties that the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission had, then suggesting standardized measures to evaluate the cost and effectiveness of online ads would be a sensible first step. That would at least help us understand whether a deeper breakup of the firms’ advertising operations is necessary.

–With assistance from Elaine He.

To contact the author of this story: Alex Webb at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe’s technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”71″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.