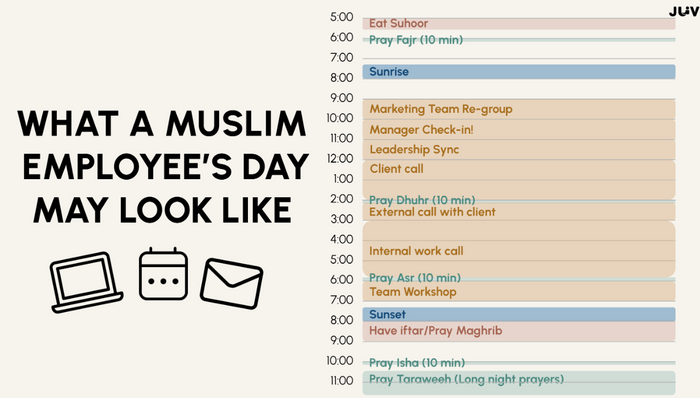

Shaina Zafar woke up around 4:50 a.m. in New York City, cooked some eggs and ate them with a bagel and coconut water before imsak, a time to stop eating and drinking. She prayed and set her intentions for the day before the sun rose. Zafar, the co-founder and chief marketing officer of JUV Consulting, went back to sleep before waking again for her work calls around 8 a.m. She had stayed up until midnight to catch up on some work after the nightly prayer.

In Toronto, Thamina Jaferi woke at 3:30 a.m. to prepare and eat suhoor, the meal before fasting — oatmeal with apples and nuts, some berries, and homemade Pakistani flatbread with minced-meat curry and yogurt — to last her until sunset. She drank two tall bottles of water and a cup of herbal tea, then prayed. Jaferi managed to get some rest before waking up again for her temporarily adjusted work start time of 10 a.m. instead of her usual 9 a.m., an accommodation she had requested a month in advance from her manager.

“Our schedule gets turned upside down in Ramadan,” said Jaferi, a senior equity, diversity and inclusion consultant at Turner Consulting Group. “You have to basically wake up in the middle of the night and start eating food.”

“‘Our schedule gets turned upside down in Ramadan.’”

The Muslim holy month of Ramadan falls on the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar; Muslims abstain from food and drink from dawn until dusk for 29 to 30 days, and also follow a prayer schedule and pray five times a day. For some, this also includes a lengthy additional prayer at night or in the mosque.

This year, Ramadan began the evening of March 22 or March 23, depending on Muslims’ geographic location and sect. It will conclude with Eid al-Fitr, the festival and celebration at the end of April that includes feasts, gift-giving and prayers. This year, Eid is expected to fall on April 21 or April 22 in North America, depending on the first sighting of the new crescent moon locally.

For Muslims observing Ramadan, fasting can make their energy levels fluctuate, and many might suffer fatigue and headaches. Taking into account potential family responsibilities, the month can be especially taxing on an emotional and physical level. When it comes to planning sleep schedules and work meetings, Muslim employees add, it’s always a game of strategy: While work schedules in many Muslim countries shift during Ramadan, workers in the U.S. and other countries must work around their existing school or job schedules.

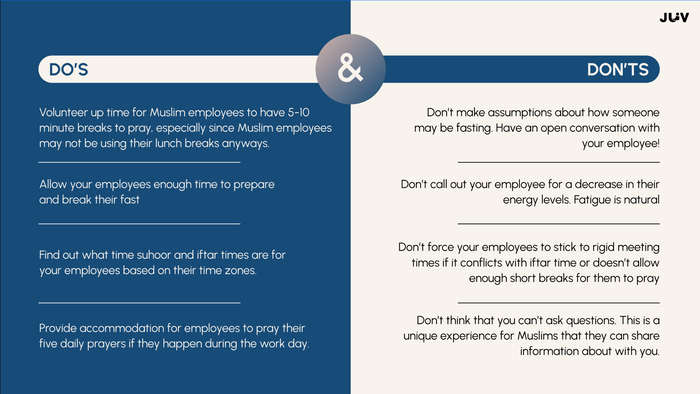

Companies and managers should take proactive steps to be inclusive of employees observing Ramadan, experts and advocates say, rather than putting the onus entirely on workers. But workers should also know their rights so they can advocate for their own accommodations, they add.

Knowing your rights and seeking accommodations

In the U.S., reasonable accommodations for a worker’s religious practice are a protected right under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employers from discriminating against an individual because of their race, color, religion, national origin or sex. The law requires an employer to provide a “reasonable accommodation” to an employee’s religious practice unless doing so would create “undue hardship” — meaning significant difficulty or financial expense — for the business.

Reasonable accommodations and undue hardships are evaluated on a case-by-case basis, but in general, courts have sided with employees who are denied accommodations, according to Muslim Advocates, a national civil-rights group representing American Muslim communities. Weighing undue hardships would involve considering the cost of the accommodations, as well as their potential to put workplace efficiency or safety at risk or infringe on other employees’ rights, the group said in a fact sheet. Religious accommodations can vary depending on the person, and can include scheduling changes or reassigning responsibilities and tasks, Muslim Advocates said.

It’s important for Muslim employees, especially more junior ones, to know their rights so they can ask for what they need, career experts said.

“Am I asking for too much?”, “I don’t really need this,” and “They don’t even need to know that I’m fasting” are all concerns that run through younger employees’ minds, Jaferi said. The same goes for employees caring for children or elders at home, she added.

What workplace accommodations for Ramadan might look like

Knowing about Ramadan is one thing, but understanding what accommodations might look like is another, inclusion experts said.

Jaferi said she once overheard a manager telling a Muslim employee on the phone that they would not accommodate the employee’s sleeping schedule. While she didn’t say anything at that moment, she said she felt upset on the employee’s behalf.

Sleep schedules should be the main accommodation managers provide during Ramadan, Jaferi said. Jaferi, for her part, asks to adjust her work hours so that she can get a bit more sleep in the morning. She breaks up her sleep throughout the day into three-hour increments so that she can make sure she meets her prayer schedule and maintains her energy level at work, and sometimes takes a short nap during her lunch break.

Zafar, meanwhile, blocks off her calendar for the Friday prayer at 1 p.m., when she heads to the Islamic Center at New York University. She also schedules small breaks for prayers throughout the day.

“‘Am I asking for too much?’, ‘I don’t really need this,’ and ‘They don’t even need to know that I’m fasting’ are all concerns that run through younger employees’ minds.”

For younger workers transitioning from school to work, Ramadan might be more taxing because of the shift from sitting in lectures to actively participating in meetings, Zafar said. And that’s where the flexibility of working from home can help.

Working from home during Ramadan is “like a dream come true,” Jaferi said. Having the ability to work remotely brings a sense of control to not only your sleeping schedule but also to the space, temperature and environment you might need for your body during a fast, she said.

Jaferi’s most grueling Ramadans have been when she had to commute to work every day, meaning she had to stay up after waking up around 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. Jaferi has sometimes had to bring a humidifier into the office, because the dry air made her feel more dehydrated when she wasn’t drinking water during the day.

One time, she got a nosebleed in the office. Jaferi dealt with it in the washroom, and her manager checked in on her. “They were really nice, but I don’t really think they truly understood what I was going through,” Jaferi said.

Zafar’s company JUV Consulting published a guide for companies on Ramadan.

Courtesy of JUV Consulting

With Eid approaching, allowing workers the flexibility to take days off is essential, Jaferi said. The festival is celebrated from one to three days, depending on the country and the community. Because Islam uses a lunar calendar, the dates vary by year and geographic location. Muslim employees might not know the exact days they need off ahead of time, she added.

“I would just tell [my manager] in advance, ‘Hey, it could fall from this day to this day, and let’s plan for contingency,’” Jaferi said.

However, contingency planning might look very different from industry to industry, and is generally easier for office workers than for those whose work requires physical labor, Jaferi said.

For workers in the service sector, she recommends giving managers and coworkers an early heads up, and considering options such as taking on early shifts instead of nighttime ones.

‘A really isolating experience’

Still, many Muslim employees face psychological barriers to seeking workplace accommodations, experts said. Being Muslim at work can be a lonely experience: Muslims account for only about 1% of the U.S. population, by some estimates, despite making up a quarter of the global population.

“A lot of Muslim employees feel like they’re asking for too much when they don’t think there’s a certain majority of Muslim employees out there in workplaces,” Zafar said. “It’s a really isolating experience to feel like you have to go to your manager and advocate for yourself.”

That feeling of isolation is compounded by the heightened stereotyping and Islamophobia that Muslim communities in the U.S. have experienced since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and its state and local counterparts have seen a “significant increase” in workplace-discrimination charges filed since 9/11 by individuals perceived to be Muslim, Arab, South Asian or Sikh, according to the agency.

Islamophobia in the workplace can take on many forms, including not only bias and discriminatory behavior but also workplaces’ or coworkers’ failure or refusal to accommodate religious or dietary needs, according to an infographic by Turner Consulting Group.

More than two-thirds of U.S. Muslims in a national 2020 survey by the University of California, Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute said they had personally experienced Islamophobia at some point in their lives, and 94% of respondents said Islamophobia impacts their mental and emotional well-being.

“Whenever there is a terrorist attack, Muslims all the time feel as if they’re going to be held responsible,” said Hira Ali, a London-based executive coach, speaker and leadership-development specialist who contributes regularly to the Harvard Business Review. (Many Muslims in the U.K. also face discrimination and Islamophobia, surveys and studies have shown.)

“I am a woman of color and [an] Asian woman. I’m a working mom, I’m an immigrant, and I’m a Muslim woman,” Ali told MarketWatch. “But I have seen that me being a Muslim received the most hateful comments from people than any of my other identities.”

Islam is not a monolith: People have different racial identities, ethnicities, lived experiences and languages, Ali said. But most Muslim people living in Western societies experience Islamophobia, she added. This could make Muslim employees reluctant to disclose their religious identity, let alone ask for workplace accommodations, experts said.

‘The responsibility lies with the organization’

Because of the stigma Muslim employees already face, pushing for change should not be a personal obligation for Muslim employees, Ali said — rather, organizations and managers should initiate conversations to make the workplace more inclusive.

Companies can promote cultural awareness by creating an inclusive schedule for employees with faith-related needs, opening discussions to hear people’s concerns and thoughts, bringing in guest speakers and senior role models of the same faith, and designating private rooms as interfaith areas where employees can pray, Ali wrote in a Harvard Business Review article last year.

Faith inclusivity remains a taboo workplace topic in many countries, and is often not included in diversity, equity and inclusion conversations, Ali said.

JUV Consulting’s second annual business iftar at Zooba gathered more than 30 business leaders in 2023.

Courtesy of Shaina Zafar

Providing employees with frameworks and templates to carry out reasonable-accommodation conversations is crucial for building a more inclusive environment for Muslim employees, so they don’t have to repeatedly explain their situation to managers, experts told MarketWatch.

These might take the form of monthly communications such as newsletters, or a company-wide announcement: For example, the company can issue communications at the beginning of the month and before important dates such as Eid al-Fitr so that managers and employees are aware of any expected changes, according to a Ramadan guide by Zafar’s company, JUV Consulting.

“You can’t really advocate for yourself if your work environment doesn’t even know if this is happening,” Zafar said.

However, workplaces sometimes fail to take proactive steps, and employees must approach the situation themselves. If it comes to that, Ali said, Muslim employees can start by talking to coworkers or managers one on one about their concerns, and seek out allies. Take note of the company’s diversity initiatives, she added, and consider starting an employee resource group.

“The responsibility lies with the organization first and foremost,” Ali said. “But if the organization is not stepping up, then I would say you would need to build a case. And how do you build a case? You definitely need to rally support.”

But the most important thing Muslim employees can do is take care of themselves, and only take on this work if “you can do it in a safe way where you’re being listened to” and “if you have the mental capacity,” Ali said.

Zafar’s company JUV Consulting published a guide for companies on Ramadan.

Courtesy of JUV Consulting

Non-Muslim coworkers can offer compassion, collaboration and flexibility

Non-Muslims in the workplace can support their Muslim colleagues during Ramadan in a number of ways, experts said: They can offer to take over or swap shifts to allow Muslim workers to pray for five to 10 minutes, for example. When it comes to meeting invites, coworkers can be mindful of the timing of suhoor and iftar and avoid those time slots. They can also avoid scheduling early-morning meetings to allow Muslim coworkers to get some sleep.

This is also a time when teamwork can come in handy, Zafar said. For example, her coworker has offered to have other team members participate more during calls so that Zafar can “piggyback” instead of bearing the entire public-speaking portion of the meeting, which is draining.

Shaina Zafar and Ziad Ahmed, co-founders of JUV Consulting, at their second annual business iftar in 2023.

Courtesy of Shaina Zafar

Eating and drinking in front of fasting Muslim colleagues is OK, Ali said, but avoid or reschedule events that are focused on food or drink. Ask about Muslim coworkers’ needs when scheduling networking events and workplace gatherings, she added. Depending on the time zone and different geographical locations, some Muslim employees might be fasting for a longer time with earlier sunrise and later sunsets.

Coworkers can also offer to be a sounding board when a Muslim employee has concerns about asking for accommodations, experts said. Understanding and compassion on the part of coworkers and managers are crucial for Muslim workers, they added.

Awareness of Ramadan and religious accommodations for Muslims is growing, but it has a long way to go, experts told MarketWatch.

Zafar’s Ramadan is devoted to hosting many iftars, the evening meal to break the daily fast, which will bring together friends, family, colleagues and young professionals in the community. Last year, when she and her co-founder invited CEOs and chief marketing officers to an iftar, people with two decades of experience in the corporate world approached them and said, “This is the first time I’ve been invited to a business-related iftar,” she said.

“My co-founder and I had just graduated that previous year, so we were expecting to be invited to iftars,” Zafar said. “Instead, we were the ones hosting them.”