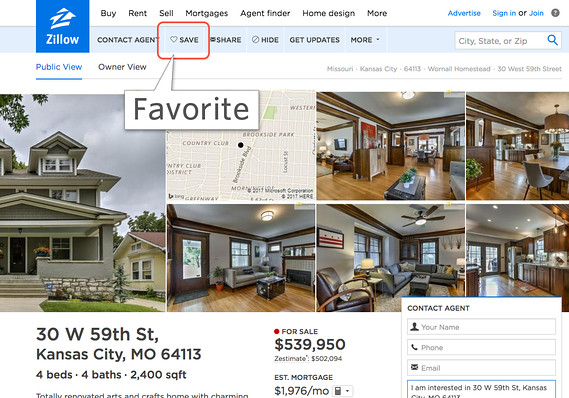

MarketWatch photo illustration/Zillow

MarketWatch photo illustration/Zillow

Another potential blow has been struck against the longstanding way in which real-estate agents get paid.

In April, the Department of Justice wrote to CoreLogic, a real-estate software provider, demanding that the company turn over information on how it works with Multiple Listing Services, the locally owned and operated compilations of real estate data.

The “civil investigative demand” concerned potential antitrust law violations, Justice said, specifically “practices that may unreasonably restrain competition in the provision of residential real-estate brokerages services in local markets in the United States.”

It’s not the first time that Justice has taken an interest in how competition gets stifled in the residential real estate market. And the April demand joins another high-profile legal case: a lawsuit filed in March which charges that real-estate brokerages and their industry group conspire to keep agent commissions artificially high.

In the American way of transacting real estate, buyers never have any reason to demand a higher level of service or a lower fee from their own broker since the seller is essentially paying the tab for both sides. And often, when sellers try to offer fees lower than the 3% that’s standard across most of the country, brokers tend to steer buyer clients away from those listings even if the house was a good fit.

Related: The lawyers who took on Big Tobacco are aiming at Realtors and their 6% fee

Against that backdrop, in an industry that has resisted change and operated with an “I’ll-scratch-your-back…” ethos, an overhaul of the MLS, the information infrastructure of the industry, might be the ultimate example of a revolution underway.

“I think everyone smells change in the air,” said Glenn Kelman, CEO of Redfin, a discount real estate brokerage, one of the earliest disruptors to try to take on the established way of brokering residential real estate. “Certainly everyone in the industry either acknowledges [change] or embraces it,” he said.

Read: Redfin CEO: Technology is finally ready to change how you buy and sell your house

The MLS is often referred to as a singular entity, but there are hundreds of iterations. Each aggregates information on properties available for sale in its local area. The National Association of Realtors describes it this way, playing up its benefits as a pool of listings: “The MLS is a tool to help listing brokers find cooperative brokers working with buyers to help sell their clients’ homes. Without the collaborative incentive of the existing MLS, brokers would create their own separate systems of cooperation, fragmenting rather than consolidating property information.”

The Justice Department has long been interested in how the various MLS operate. As MarketWatch was one of the first publications to report, last year a decade-long consent decree against NAR was lifted. That agreement was reached in 2008 after local real estate associations and listing services spent years refusing to allow listing access to upstarts like Redfin, which can tend to undermine an agent’s role in the process and engage the consumer in the house hunt.

See also: Realtors will soon be free of 10-year-old Justice Department decree — what happens to housing now?

But a decade on, things have changed, thanks in large part to technology companies like Redfin RDFN, -3.84% , Zillow ZG, -1.74% , and even Realtor.com, a venture owned and operated by News Corp., the owner of MarketWatch.

As Rob Hahn, founder and managing partner of 7DS Associates, a real estate consultancy, put it, “the cartel has been broken when it comes to listings. Zillow has all the buyers. The moat today is the hidden information, the sold data, off-market data and agent commission.”

Agent commission is clearly what’s of interest to Justice now. The very first item on the list of demands sent to CoreLogic CLGX, -2.00% was “all documents relating to any MLS member’s search of, or ability to search, MLS listings on any of the company’s multiple listing platforms, based on (i) the amount of compensation offered by listing brokers to buyer brokers; or (ii) the type of compensation, such as a flat fee, offered by listing brokers to buyer brokers.”

The information in question is typically available on the MLS but not third-party industry sites like Zillow or Redfin. But even if such information is not displayed on the MLS, it may be searchable or downloadable, which is why Hahn thinks DoJ is focusing on “any MLS member’s search of, or ability to search, MLS listings.”

Read: Meet the tech-savvy upstarts who think they can finally give Realtors a run for their money

In U.S. residential real estate transactions, agents representing both the buyer and the seller are paid from the proceeds of the sale. That means that technically the seller pays the commission of both his own agent and the agent representing the buyer. Of course, anyone in the industry, or anyone who’s bought and sold real estate often enough is keenly aware that’s not entirely true.

“Ultimately the buyer is paying for it,” said Daren Blomquist, vice president of market economics at Auction.com. “It’s baked into the price of the property. How the gatekeeper of the transaction is paid is something a lot of folks don’t completely understand and that’s what’s at the heart of some of these legal actions.”

It is important to note that while there is evidence that real-estate agents steer clients away from listings offering lower commissions and for-sale-by-owner transactions, as noted in earlier reporting, the precise impact of such actions haven’t been well-quantified. As Hahn notes, more research could determine whether those properties linger on the market longer, sell for less, some combination of those two, or something else altogether.

See: Sell your home with a Realtor or an algorithm? Maybe both.

Making it easier for consumers to understand transactions may be at the heart of the legal actions, but making it more enjoyable — or at least less painful — to do the deal is core to many of the new ideas and billions of dollars flooding into the housing market recently.

“Consumers are pissed off,” Hahn said. “There’s more and more sentiment from consumers that Realtors don’t earn their pay.”

Entrepreneurs, including from tech clusters like Silicon Valley where the disrupters may have little actual real estate experience, smell opportunity. “There’s money involved, is the bottom line,” Blomquist said. “Housing is really a multi-trillion dollar industry and that translates into tens of billions in commissions to the gatekeepers of those transactions. As we’ve seen some of these start-ups come out of the woodwork over the last few years, trying to disrupt the industry, that’s code for ‘we want to take a piece of the pie.’”

Read: ‘So remarkably inefficient’: Venture capital takes on the housing market

Blomquist has spent several decades working for real estate data providers. MLS data is “a great complement” to public records data like deed transfers, and there may be privacy concerns about how much data should be made widely available, but generally, it was a “protectionist” industry trying to guard its information that makes MLS data off limits to private companies, Blomquist said.

Now, industry participants like Glenn Kelman say the DoJ’s interest is a good thing. “The two sides were dug in a decade ago over who could have access to the listing data,” Kelman told MarketWatch. “In comparison I think this is a much more tractable problem to solve and I’m excited about it.”

Related: You’re being watched — home sellers are using spycams to monitor buyer traffic