Getting to work in the mornings can be a struggle for Angelina Flood.

On a good day, it can take at least an hour for her to drive from the home she and her husband bought in Southborough, Mass., to her job as an editorial assistant in Cambridge, Mass., just outside of Boston.

To avoid the traffic, she gets in at 7 a.m. and works until 3 p.m. three days a week. “The commute is hellish,” Flood, 27, said. “If I liked my job less it would be a big problem.”

In spite of that commute, Flood said she and her husband have no regrets about becoming the owners of a home in the exurbs. The couple loves the privacy living further out from Boston affords them — they have a huge yard with lots of trees, room for their dog to play and space to add onto their home if they want.

And in less than five minutes, they can get on the highway and drive to larger towns or Boston for anything they can’t find in Southborough.

The Floods are far from alone. Housing experts have heralded the return of the exurbs. Sky-high home prices and rising mortgage rates have forced home buyers to look beyond city centers and nearby suburbs when looking for a property to buy. Millennials looking to buy their first homes and retirees searching for affordable places to downsize alike are flocking to these communities.

Also see: Is Trump’s tax law helping or hurting the housing market?

And their attention is focused on the exurbs — the less-densely populated, often newly constructed communities on the outskirts of major metropolitan areas. “In a growing economy, that is where you see sales pick up,” said Javier Vivas, director of economic research at Realtor.com.

There were 7% more single-family homes built in exurban areas in 2018 than the year prior, according to research from the National Association of Home Builders. During that same period, home building activity only increased 3% overall.

But underlying today’s exurban fervor is an uncomfortable truth: The reason that homes in these communities are so affordable is that these areas were among the hardest-hit by the housing crisis and recession, and prices have only recently recovered.

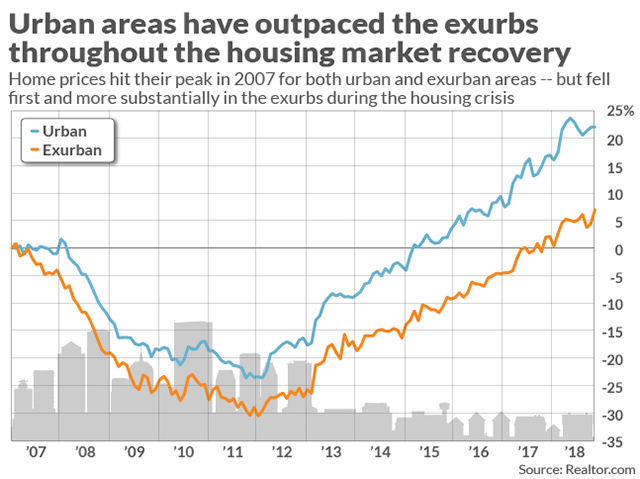

A new study from Realtor.com explored how much more volatile home prices are in the exurbs than in more densely populated parts of the country. Realtor.com defined exurbs as ZIP codes where the household density fell within the 25th percentile, while urban areas’ density fell in the 75th percentile.

“It’s the exurbs that will take the hit first and recover later,” Vivas said, summarizing the study’s findings.

(Realtor.com is operated by News Corp NWSA, -0.63% subsidiary Move Inc., and MarketWatch is a unit of Dow Jones, which is also a subsidiary of News Corp.)

Sales prices in urban areas bottomed out at 24% below their 2007 peak when they hit the recession-era low in the fall of 2011. At that point, sales prices in the exurbs had fallen 24% below their 2007 peak two years earlier — and bottomed out at 31% below their peak.

Following the recession, sales prices in cities recovered by early 2015 and are now 22% above their pre-recession peak. Comparatively, sales prices in the exurbs didn’t return to their pre-recession peak until mid-2017 and have only exceeded that amount by 7% until now.

‘It’s the exurbs that will take the hit first and recover later.’

Why home prices in the exurbs are more volatile

The exurbs epitomized the problematic lending standards that stoked the housing market downfall that sparked the last recession. “The markets there were built on a faulty foundation,” said Daren Blomquist, vice president of market economics at real-estate website Auction.com. “It was a drive-until-you-qualify-type thinking.”

The loose lending standards employed by many banks made it easy to get a loan that would make buying a home possible. That inflated demand, which in turn fueled rising home prices further and further out from major cities.

Read more: Where mortgage payments take the smallest bite out of people’s bank accounts

Builders in turn constructed expansive communities far from urban centers. When the gravy train ran dry though, these homes went without buyers, prompting the precipitous decline in home prices there.

But lending standards alone don’t explain the more dramatic price fluctuations the exurbs experience. There’s a much simpler explanation. “They’re far from any jobs or services,” said Jim Belfiore, a real-estate industry consultant.

Especially outside Sun Belt cities, exurbs are often purely residential communities, with nary a school or supermarket. When housing demand is high, buyers will relent and purchase in these areas because they’re relatively affordable. When demand is low, though, many people are inclined to hold off because they simply want to live closer to where they work and play.

When the housing market cools, will the exurbs suffer?

The recent uptick in home sales aside, the U.S. housing market has slowed down significantly in recent months. Home price appreciation has fallen off its breakneck pace of recent years, and housing experts expect that trend to continue. And with the threat of a potential recession looming, people’s interest in buying a home could wane.

Additional research from Realtor.com has found that the housing market cooldown is affecting urban areas the most.

Also see: Why home buyers could be forced to shrink their budgets in 2019

Home list price growth still remains strongest in urban areas (up 7% in February) than in the suburbs (up 5%) and exurbs (3%). And homes generally still stay on the market much longer in exurban areas (85 days) than urban areas (66 days).

But starting last fall, urban areas began to see notable growth in the number of homes listed for sale. And the inventory of available homes has grown more in urban areas than in the suburbs or exurbs. Homes in urban areas also saw the weakest growth in the number of views per online listing and started staying on the market longer.

“Finally affordability is catching up with those areas and is slowing down demand for properties there,” Blomquist said. And that trend, he said, could ripple into the exurbs.

‘In the exurbs, the people who are buying there truly can afford it.’

If it does, that could spell trouble for home owners and investors in those areas. Making matters worse is the fact that builders haven’t necessarily learned their lesson.

Yes, the construction of single-family homes has only recently begun to pick up in pace in recent years. But some of the development projects in the exurbs look an awful lot like the pre-recession communities that sat vacant for years, Belfiore said.

In the Phoenix area, where Belfiore lives, a number of new communities are in the planning stages. And like the last time around, the homes will come first, and then retail locations and restaurants will be built.

“Rooftops drive retail,” Belfiore said. “The model’s already committed.”

Thankfully, the lending standards that are the industry standard these days should provide a cushion. “Things are different this time around,” Blomquist said. “People are moving further out to be able to afford homes. The difference now is it is based on true affordability rather than faulty affordability standards. In the exurbs, the people who are buying there truly can afford it.”