(Bloomberg Opinion) — When political outsider Joko Widodo was first sworn in as Indonesia’s president five years ago, a little company called PT GO-JEK Indonesia was barely known. Their rise together since then has broken a technology barrier that was holding back the world’s fourth-most-populous country and promises the chance for a better future.

Jokowi, as he’s known, is starting his second term with the dramatic, yet pragmatic, appointment to his cabinet of Nadiem Makarim, the chief executive officer and co-founder of what’s now called Gojek, which has gone from ride-hailing novelty to one of the engines of tech transformation in Indonesia.

At the time of Jokowi’s first presidential run, his tech ambitions centered on attracting device manufacturing in a bid to diversify the economy away from dependency on mining and energy. Then governor of Jakarta, he worked hard to lure Taiwan’s Foxconn Technology Group to build a factory to manufacture iPhones and create thousands of jobs.

A deal signed with Foxconn Chairman Terry Gou in February 2014 to invest $1 billion into Indonesia amounted to a de facto endorsement of Jokowi’s economic chops, helping the former furniture maker win election as Indonesia’s first president who didn’t hail from the traditional elite or the military.

The Foxconn investment never materialized. But it never really had an impact on Jokowi’s standing as the development of Indonesia’s technology sector came from a very different direction.

A play on the word ojek, or motorcycle taxi, Gojek was mostly operating as a call center for courier deliveries and motorbike rides when Jokowi took office. Three months later, Gojek launched the mobile app that would make it one of Southeast Asia’s biggest startups, with a valuation of around $10 billion.

Today, Gojek offers ride hailing, food delivery, payments and a host of other digital products not just in Indonesia, a nation of some 265 million people, but throughout the region. More importantly for Jokowi, it has more than 2 million drivers and 400,000 merchants on its platform — creating far more jobs and livelihoods than an iPhone factory ever could.

In Indonesia, Gojek is now a national champion. Its riders vie on Jakarta’s notoriously crowded streets with those of Singapore-based rival Grab Taxi Holdings Pte, both of them oddly liveried in green and black. They notably upended Uber Technologies Inc.’s expansion into Southeast Asia and are vigorously competing around the region, total population nearly 650 million.

Now, Gojek will have a man on the inside. Harvard-educated Makarim, 35, resigned from the company Monday in order to join the cabinet, portfolio to be determined. The appointment is in line with Jokowi’s goal of bringing industry professionals and millennials into the inner circle.

It’s hard to discern who’s the bigger winner. Imagine Mark Zuckerberg resigning from Facebook Inc. to join President Donald Trump’s cabinet. Neither carries the baggage of their American counterparts. But Makarim is a political novice and risks becoming just one more pawn in the constant maneuvering that consumes Indonesian governments.

Jokowi set policies in motion early in his first term to open the economy. They have had mixed success. A deep streak of economic nationalism has long frustrated foreign direct investors. Growth has chugged along at a steady 5% for years. He has struggled against entrenched interests. Yet at a time when regulators and traditional taxi companies worldwide were pushing back against ride-hailing companies, Jokowi’s government refused to crush them. His biggest contribution may have simply been to get out of Gojek’s way.

Being a local favorite hasn’t hurt Gojek. It now has a coveted e-money license, allowing it to offer financial services to millions of customers who don’t have a bank account or credit card. Grab now gets around this by teaming up with local partner OVO.

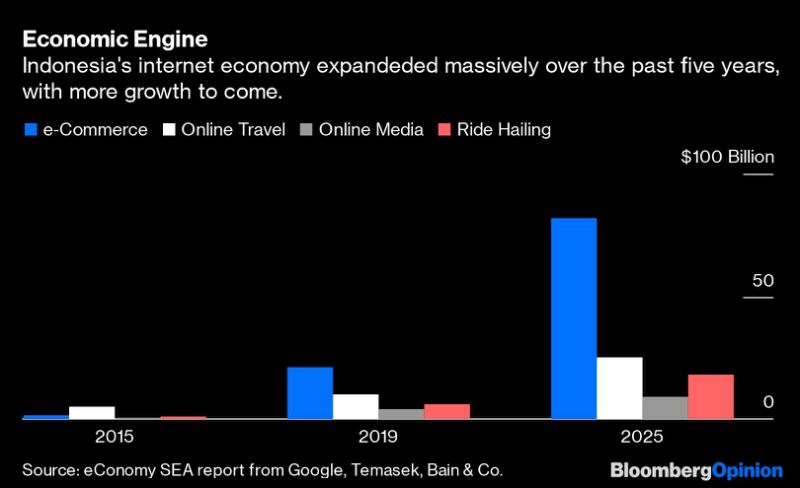

Gojek isn’t alone in Indonesia’s expanded tech universe. Online travel provider Traveloka, e-commerce company Tokopedia and online marketplace Bukalapak have all become unicorns. From $8 billion in 2015, the internet economy grew to $40 billion this year and will triple again to $130 billion by 2025, according to a research report from Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Temasek Holdings Pte and Bain & Co.

The common element: Each operates in a space called O2O, or online-to-offline. They leverage internet technology to deliver physical-world services, helping people eat, shop, and travel in a nation where infrastructure is unevenly parceled out across 18,000 islands straddling the Indian and Pacific oceans.

A strong and viable digital services economy employing millions was an accidental achievement of Jokowi’s first term. It may not be enough to sustain future economic growth, however. The president and the entrepreneur will need to sit down and write the second act.

To contact the author of this story: Tim Culpan at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Patrick McDowell at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Culpan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. He previously covered technology for Bloomberg News.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”41″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

Add Comment