maruccisports.com

maruccisports.com In 2014, MarketWatch wrote about Scott Carpenter, who made a modernized version of the baseball glove out of his home. He made each one based on a mold or sketch of the user’s hand and used synthetic materials that made the gloves lighter and easier to break in than traditional leather gloves. The title of our story asked, “Is this the baseball glove of the future?”

Carpenter now makes gloves in a new glove-making lab in Cooperstown. That’s one of many changes that have occurred since Marucci Sports acquired Carpenter’s company, Carpenter Trade LLC, in 2018. Marucci Sports is less than 20 years old and already has more MLB players using its bats than any other brand, Carpenter says, adding that he hopes the company makes similar strides with baseball gloves.

“I couldn’t be happier with the situation with Marucci. It’s kind of perfect in a lot of ways,” Carpenter recently told MarketWatch. “We have a common vision of disrupting the glove market. Marucci is better suited to do it than most other brands.”

Marucci owns “everything” Carpenter designed and invented. In exchange, he is now the company’s master glove designer. Carpenter, 48, says his top motivation to sell was to get to the next level — “to make the best gloves for the best players on the planet. To make the best glove in baseball, period.” He says he knew he’d have to partner with a larger company to take advantage of things like 3-D technology.

He also received money for being acquired, and says, “It was worthwhile financially. I’m less worried now about retirement and benefits after working for a number of years below the cost of living.” Marucci is based in Baton Rouge, La., and it has production partners in China. Carpenter has traveled to both locations several times since the partnership began.

The CMOD glove — traditional leather on the outside with a high-tech inside

Carpenter had success with his all-synthetic gloves — in 2011 pitcher Brian Gordon was called up by the Yankees to make his MLB debut and he used his Carpenter glove, which is now in the Hall of Fame as the first all-synthetic glove used in a game. But Carpenter realized around 2015 that his reputation in the baseball world was that he made an all-synthetic glove, and that they were seen as a curiosity or novelty. He made a business decision then to change his reputation, to better convey that he used “a lot of technology and engineering to make a better glove.” So he started modifying other brands’ gloves — for example, Rawlings, Wilson and Mizuno. “I’d take them apart. Rip out the lining and padding, and reinsert my own technology into the glove and put it back into the same outer shell, he says.” He called it a CMOD — for Carpenter modification — and says it showed people that what he did enhanced the performance of existing gloves. “And it all led to the acquisition” by Marucci, he says.

Since partnering with Marucci, he has an All-Star major leaguer using a CMOD, and hundreds of CMODs recently went on sale to the public.

Josh Donaldson, who was the American League MVP in 2015 and has been an All-Star three times, was already using a traditional Marucci glove, but since Carpenter joined the company he started using a CMOD.

Donaldson says ”the CMOD technology takes a lot of weight out of your glove,” and adds, “it’s form fitting, to where you’re going to have more control over your glove…it’s almost like a glove inside of a glove.” He says it allows him to be very accurate, especially when on the run. He calls it “a real game-changer.”

Carpenter made Donaldson’s glove based on a sketch of his hand, and will personally make gloves for other MLB players who use a CMOD as well. The gloves that recently went on sale for consumers were made in China. Carpenter went to China and sat with the glove-making team there to walk them through the process step-by-step, according to Eric Walbridge, vice president of soft goods for Marucci, which includes fielding gloves, batting gloves and equipment bags. He says Marucci started selling 300 CMODs on Jan. 20.

Marucci also sells traditional baseball gloves, without the Carpenter modifications. The prices for those range from $89 to $350, and the price for CMODs is $350. Walbridge says Marucci started selling baseball gloves in 2013 and it was “really smart to go after Scott” to do something different to stand out while competing against companies like Rawlings and Wilson, the two biggest sellers of gloves in the world.

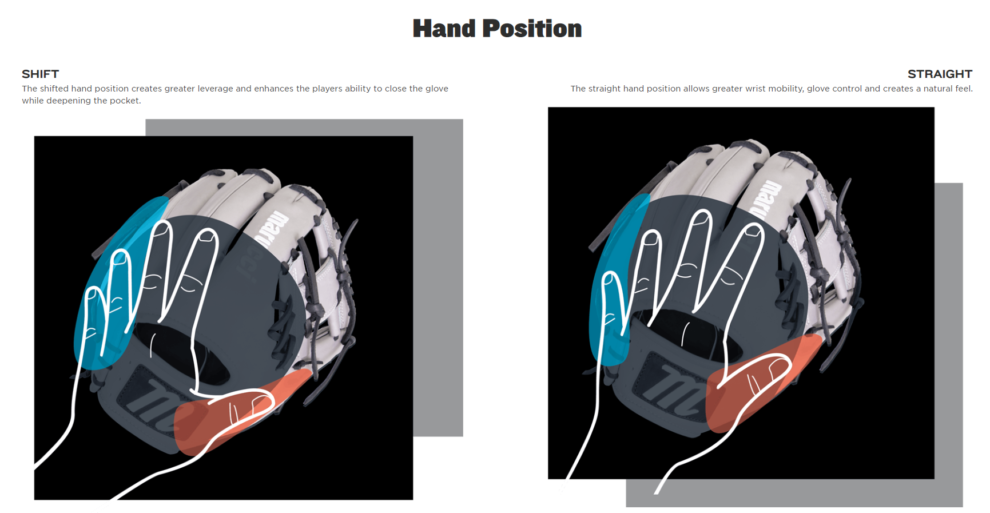

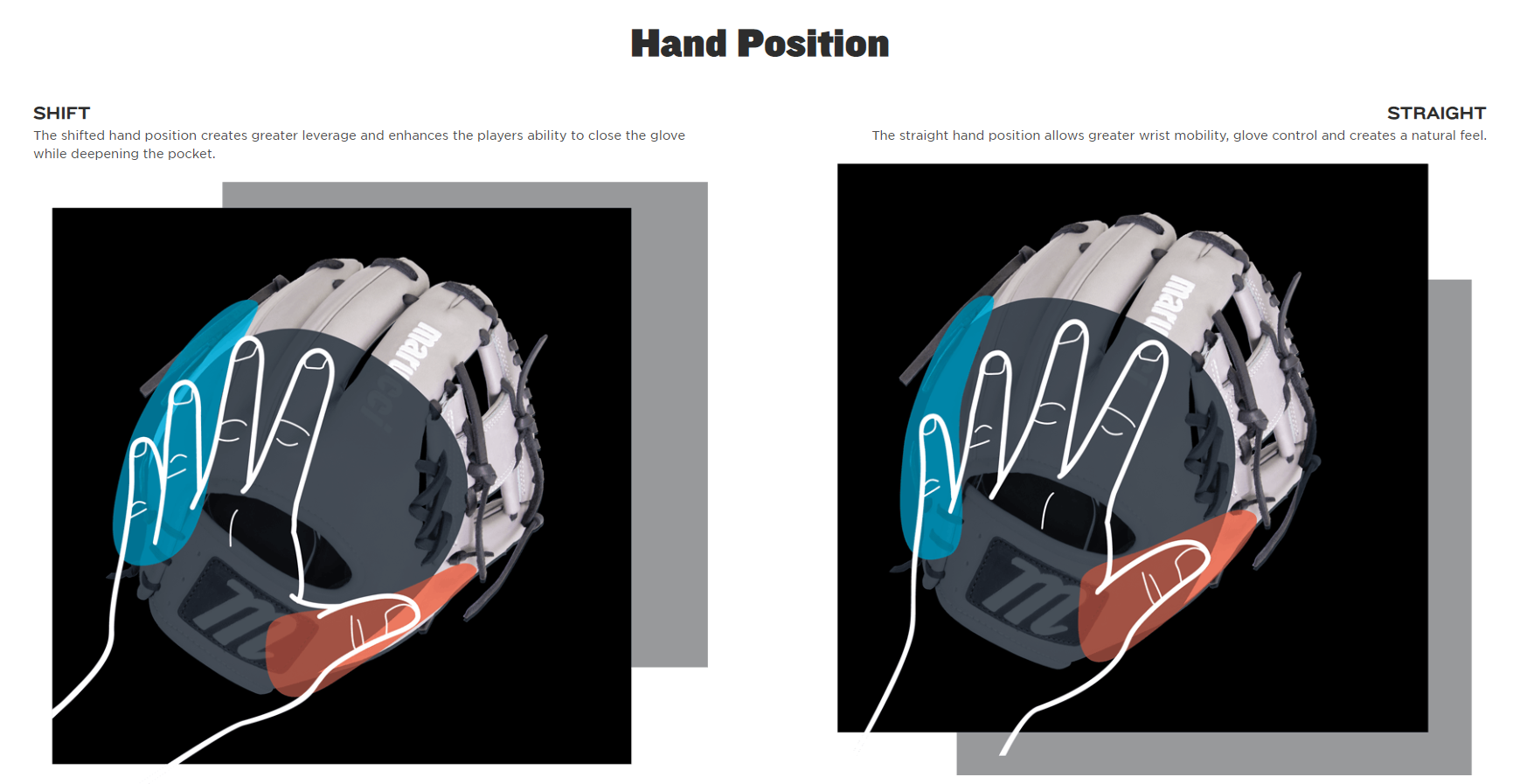

For the gloves currently on sale on Marucci’s website, Carpenter designed injected molded parts via 3-D modeling and printing. Another thing that makes these CMOD gloves different is that they come in different sizes (most companies only sell adult and child sizes, Carpenter says). Currently you can buy a medium or a large, and the company has plans to add many more sizes, including extra small, small and extra large. It also comes in two different hand positions — shift or straight (see graphic above for the difference). It’s a few ounces lighter than a traditional all-leather glove because some of the leather on the inside is replaced with synthetics.

“When you squeeze this glove, you have better leverage. More than with a thumb loop, which pulls to the right or left,” Carpenter says. “It’s hard to describe, but you notice it immediately when you put it on.”

What’s next

Carpenter says not much has changed in the making of baseball gloves in the past 50 years, and his goal is to lead on the evolution of the baseball glove. “Marucci is in a unique position. Most other brands don’t have someone like me in the U.S. physically making gloves every day. Most rely on factory partners overseas,” he says.

Walbridge says a goal for the company is to have more MLB players using the gloves. “This spring training we’ll be showing the CMOD and discussing it with a lot more players,” he says.

div > iframe { width: 100% !important; min-width: 300px; max-width: 800px; } ]]>