This is the first in a six-part series of stories about programs that offer high-school students the opportunity to take college classes. The series was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program. (Read part two here.)

There’s not much Barack Obama and Betsy DeVos see eye-to-eye on.

But the 44th president of the United States and the Trump administration’s controversial education secretary have found some common ground.

Obama and DeVos — as well as many local, state and federal politicians — have heralded the idea of students taking college courses and earning college credits while still in high school.

Students who earn college credits while in high school will theoretically take fewer credits while in college — making their tuition costs cheaper.

“We need to give every American student opportunities like this,” Obama told members of Congress and the American people during his 2013 State of the Union address.

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos suggested to lawmakers last year that “more schools adopt this really meaningful and important option for students.”

Fueled by this enthusiasm, the concept — known as dual enrollment, dual credit or concurrent enrollment — has gone from a niche enrichment opportunity to an increasingly common part of the high-school experience.

These opportunities have expanded rapidly even as questions remain about how effective they are at tackling some of the pernicious problems they’ve been tasked with addressing: College affordability, closing gaps in access to higher education and more.

“I don’t know if we’ve sorted out what we want from this,” said Alec Thomson, a professor at Schoolcraft College, a Livonia, Mich.-based community college, who has written critically about the expansion of dual-enrollment. “It has great promise, but I worry that we’re over recruiting for a program that doesn’t address the basic needs of people who are struggling.”

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

The opportunity to take these courses has ramped up dramatically

The appeal to politicians, school leaders and families of earning college and high-school credit at the same time is obvious in a world where student debt continues to climb. Students who earn these credits while in high school will theoretically take fewer credits while in college — making their tuition costs cheaper. Anything localities and high schools can do to cut down on the cost — and financial risk — of college is a welcome effort.

Research also suggests that programs that provide exposure to college early, like dual-enrollment, could help students who might not otherwise consider higher education become comfortable with the idea of going to college. Early college exposure can also help prepare students who are set on going to college, but whose families have little experience with it, succeed.

‘It has great promise, but I worry that we’re over recruiting for a program that doesn’t address the basic needs of people who are struggling.’

That’s valuable in a world where a college degree is becoming increasingly necessary to compete in today’s job market — and equal access to a degree by race, income and other factors is still elusive.

Pinning their hopes on the idea that offering high-school students the chance to take college courses could make a dent in some of these intractable problems, policy makers, school leaders and others across the country have drastically ramped up these offerings.

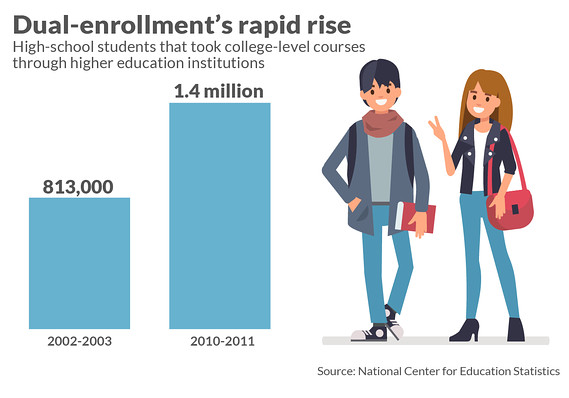

During the 2002-2003 academic year, about 813,000 high school students took college courses through higher education institutions, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. By the 2010-2011 school year that number jumped to roughly 1.4 million.

Though the most recent robust national data dates back to 2011, state-level data indicates the number of students taking these courses has continued to grow.

There are clear benefits to providing high-school students with the opportunity to take college courses. Students who take these classes are more likely to attend and persist in college, research indicates. In addition, the more rigorous course work available to high-school students, the better, both for their academic enrichment and college admissions prospects, said Barmak Nassirian, the director of federal policy at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

‘We don’t know what makes for effective practice’

But even as school districts across the country have expanded these programs, major questions remain. “We don’t know what makes for effective practice,” Davis Jenkins, a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Community College Research Center. At least not yet. His center is researching exactly this question.

Whether they’re a good investment by taxpayers — and in many cases, the students themselves — isn’t totally clear. In Texas, one of the few states with independent research on the cost of these programs, taxpayers spent about $121.7 million in one year on them. While research shows they reaped a return on that investment, we don’t know whether that money could have produced better results if spent differently.

Whether taking college credits in high school is a good investment by taxpayers and the students themselves isn’t totally clear.

There’s limited evidence on how the college credits students earn in high school are applied toward their college degrees and whether they wind up saving the students money. And if students, parents and others are expecting that outcome, the courses should be equivalent to what students experience in a college classroom, Nassirian said. That isn’t always the case, he added.

In some instances, high-school students are taking courses in a college classroom with college students; in others, they’re on a college campus learning from a professor, but in a classroom filled only with their peers. In still others, these courses are taught by a high-school teacher inside of a high school, though the syllabus is typically overseen by a college.

‘Policymaker and parental terror’ are motivating the expansion

There’s nothing wrong with offering more of these courses to students as enrichment opportunities; in fact, they may benefit from more rigorous course work, Nassirian said. But a key problem with the rapid growth of these programs: “Much of it may be motivated by policy maker terror and parental terror about college costs,” Nassirian said. “I do have a problem the minute you begin to say, it will shorten your college career. At that point, it really matters if the courses are equivalent or not.”

Other research indicates that in many regions, students of color and low-income students are less likely to have the opportunity to take college courses in high school — putting the programs at risk of actually exacerbating inequities already present in education instead of closing them.

Colleges and high schools partnering to offer these courses are beginning to become more thoughtful in their approach as the programs — and the scrutiny they face — has grown, Jenkins said.

Amid this backdrop, MarketWatch traveled to two regions with three different approaches to providing high school students with chances to earn college credit. The goal was to help better understand how these questions play out in classrooms and principals’ offices.

What we found: Tying high school and college more closely together presents both challenges and opportunities for students, principals and policy makers.

A six-part MarketWatch series over the next week will explore this complex issue.

(This story was originally published on May 20, 2019.)

Get a daily roundup of the top reads in personal finance delivered to your inbox. Subscribe to MarketWatch’s free Personal Finance Daily newsletter. Sign up here.