(Bloomberg Opinion) — Netflix just re-released one of the most popular animated television programs of all time — “Neon Genesis Evangelion.” The show, which combines dark, complex themes of alienation and loneliness with action-packed battles between robots and monsters, captivated the worldwide audiences when it came out in 1995 It introduced an entire generation to Japanese animation, whose high quality, adult themes and unique sensibilities helped redefine Japan’s culture in the eyes of the world, supplanting traditional visions of Mt. Fuji, geisha and tea ceremonies. But a quarter-century later, Japan is having difficulty transforming its newfound cultural cachet into economic riches.

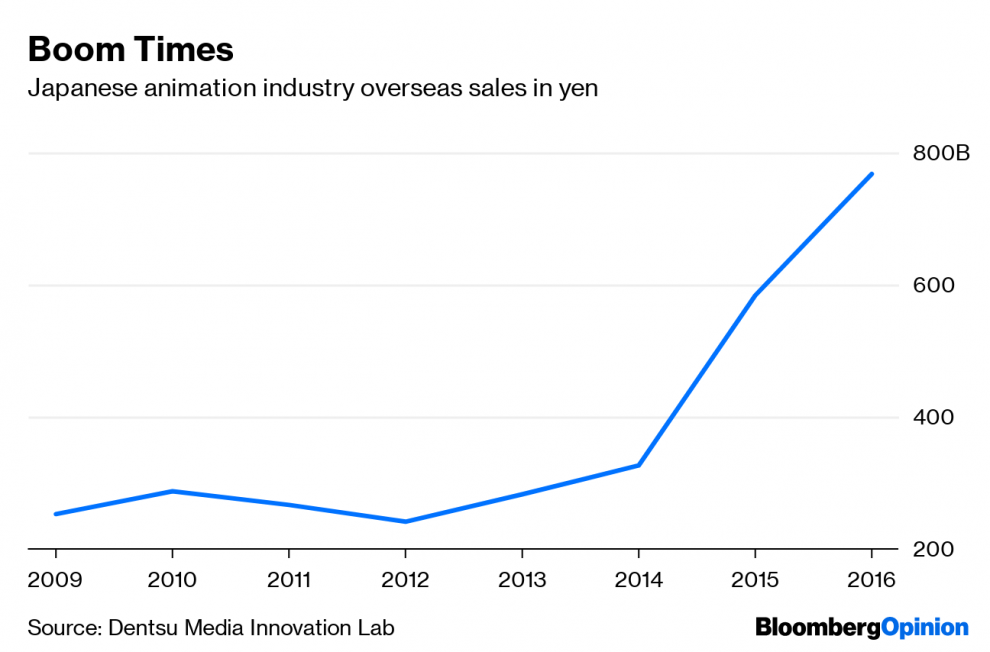

Yet Japanese pop culture is thriving, with enormous fan conventions all over the world. Thanks to platforms like Crunchyroll (owned by AT&T) and Netflix — which has licensed many TV programs from Japan, as well as ordering its own originals from Japanese studios — overseas sales have been increasing rapidly, with cartoons making up the bulk.

This is progress, but the Japanese entertainment industry could do much more. As things stand, the profits from platform distribution flow to AT&T and Netflix; if a Japanese company bought Crunchyroll or started its own worldwide streaming distribution service, those profits would go to Japan instead. Japan also has so far failed to make an internationally successful live-action movie business, despite possessing the technology to make cutting-edge visual effects that could rival Hollywood.

But the real power of Japan’s cultural cachet could go well beyond entertainment products. As the book “Reinventing Japan” noted, many of the products and services that Japan makes — cars, clothing, food, architecture, even zippers — embody a matchless Japanese esthetic sensibility. This Japanese-ness is difficult to describe, but easy to recognize. And if promoted correctly, it could be used to help increase Japanese exports.

Many people think of Japan as an export-oriented economy, but it’s more insular than most:

The lure of its large domestic market is too strong, causing many companies to look inward for safe, reliable revenues. But with the population shrinking and aging, and the rest of the world growing, that strategy makes less sense every day. Japanese companies must look outward.

Japan already has a reputation for making high quality products, but that’s not enough. Consumer branding, marketing and other consumer-facing services capture large amounts of the value in supply chains, so by increasing brand value and close contact with international customers, Japanese companies can rake in the profits. And cultural cachet provides a way to do that.

Consumers don’t just buy products because they’re high-quality; they consume a certain lifestyle. Traditionally, it has been the U.S. that captivated the hearts of global buyers. They see the freewheeling lifestyle in Hollywood movies and dream of big trucks and Levi’s jeans. Or they see comfortable suburbia and want SUVs and Crocs. Now, thanks in part to ongoing urbanization and in part to the spread of Japanese entertainment, Japanese life has captured the hearts of many of the world’s young. The country’s dense yet peaceful cities, its intricate architecture and artistry of its interior design, and its refined yet friendly culture combine to create a uniquely pleasant environment.

Any doubt about this appeal should be allayed by the scale of Japan’s recent tourism boom, which has far exceeded the targets set by the government a few years ago:

The same attraction that draws in tens of millions of tourists every year can be used to sell products. It’s a short jump from admiring Japanese life to wanting Japanese cars, clothing, food, online services, or retail experiences. Or cosmetics — Shiseido, the Japanese cosmetics giant, is seeing record sales and profits, driven by its successful attempts to export a Japanese ideal of beauty to countries like China. The challenge is to make Shiseido the norm rather than an outlier.

Japan’s government has long recognized the potential of what some have called the country’s “gross national cool.” But the government’s ham-handed attempt to capitalize on the trend, the Cool Japan initiative, has been mostly a failure. It funneled large amounts of public funds to leading advertising agencies like Dentsu and Hakuhodo, but these companies’ efforts produced few tangible results.

A new strategy is needed. Instead of going through intermediaries like Dentsu and Hakuhodo, the government should encourage entertainment-production companies themselves to export their products, using financial incentives and bureaucratic pressure. As for using Japan’s cultural cachet to market other products, the government should award contracts to a large number of smaller marketing and advertising firms instead of the big incumbents, and direct resources toward the ones that succeed in penetrating foreign markets.

Japanese companies will also have a role to play in this effort. Like Shiseido, they should strive to market their products not just as high-quality, but as conferring the stylish sophistication of Japanese culture upon anyone who buys them. They should appoint young, flexible-minded employees with international experience to lead the effort, sending more people and capital overseas in order to develop new markets.

More than two decades after Neon Genesis Evangelion first appeared on TV screens around the world, Japan is cooler than ever. It just needs to believe in its coolness.

To contact the author of this story: Noah Smith at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”67″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.