(Bloomberg) — Terms of Trade is a daily newsletter that untangles a world embroiled in trade wars. Sign up here.

Resurgent tensions between Japan and South Korea threaten to wallop chipmakers from Samsung Electronics Co. to SK Hynix Inc., upsetting a carefully choreographed global supply chain by smothering the production of memory chips and other components vital to widely used devices.

As the world fixates on Donald Trump’s campaign to contain Huawei Technologies Co. and China’s ambitions, a concurrent dispute between Beijing’s two richest neighbors also has far-reaching implications for the production of everything from Apple Inc. iPhones to Dell Technologies Inc. laptops. The industry is now scrambling to gauge the fallout after Japan — citing longstanding and unresolved tensions — slapped restrictions on exports to Korea of three classes of materials crucial to the production of semiconductors and cutting-edge screens.

That maneuver, the most recent manifestation of decades of war-time tensions, places Samsung at the center of a firestorm and again underscores the global nature of the production machine that cranks out most of the world’s gadgets. Not only does it make memory chips, but Samsung is also the biggest producer of smartphones.

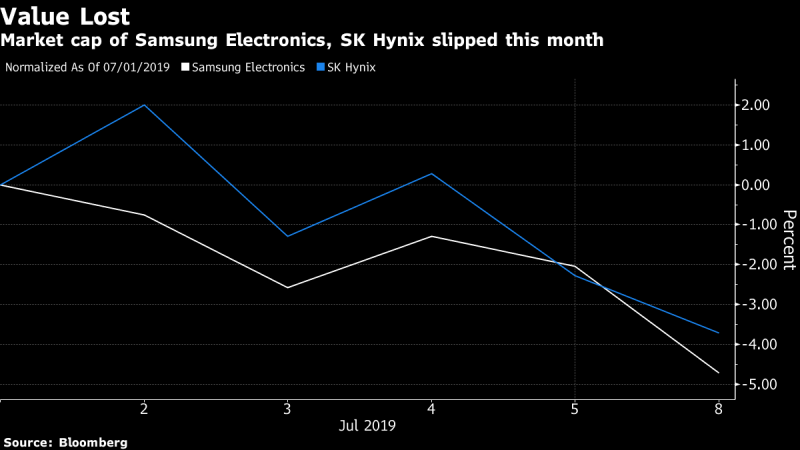

Korea’s largest company slid 2.7% Monday and has lost about 16 trillion won ($13 billion) in market value this month, while Hynix dropped 1.5% and has shed 1.5 trillion won. The two companies — which together account for 60% of the world’s memory chip-making capacity — declined to comment.

While inventory levels differ across each material, Samsung has under a month’s worth of supply on average, according to people familiar with the matter. Samsung and SK Hynix are busily sourcing alternatives, the people said, asking not to be identified talking about a sensitive political issue. The two Korean giants assured clients they would try to minimize the impact on output, but Samsung, for one, is bracing for potential production cuts or even stoppages should the situation persist, the people said.

That’s why the Korean conglomerate’s de facto leader, Jay Y. Lee, hopped on a jet to Tokyo over the weekend for emergency meetings with Japanese suppliers. It’s unclear how deeply felt the impact might be — much depends on whether Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and South Korean President Moon Jae-In can work out a compromise. But in a worst-case scenario, flexible screens for iPhones and other mobile devices could sputter, while memory chips used in everything from HP Inc. notebooks to Amazon.com Inc. servers could dwindle.

“This is an unprecedented event,” said Jongjun Won, chief executive officer at Lime Asset Management Co. “If it’s lucky, the chip industry may be able to adjust inventories. There could be a happy ending if the Japan issue gets resolved in the meantime. However, the intertwining of politics and business is making it difficult to find a solution.”

The dispute has spilled over into social media. South Koreans, angered by Japan’s move, have taken to Instagram and other platforms to call for boycotts of Japanese travel and consumer products.

Japan’s targeting a trio of materials that, while little-known outside of the industry, is profoundly important for electronics production. The government says they also have sensitive military applications. Within the tech sector, fluorinated polyimide is required for the production of foldable panels — such as those used in Samsung’s Galaxy Fold — among other things. Photo-resists are key to chipmaking, while hydrogen fluoride is needed for both chip and display production.

Finding substitutes won’t be easy: Korean corporations now depend on Japan for over 90% of all the fluorinated polyimide and resists it needs, and 44% of its hydrogen fluoride requirements, Societe Generale estimates. Ironically, if the dispute drags on, Japanese suppliers of those chemicals — companies from JSR Corp. to Shin-Etsu Chemical Co. that comprise a small but inextricable link in the chain — could take a hit as well.

“This could be a negative factor for the world economy,” Huh Nam-Kwon, CEO at Shinyoung Asset Management Co, said by phone. “All we need to do is wait and see how the situation goes. Just one word from Abe could decide anything. It’s hard to predict.”

The most significant impact will be on Samsung’s next-generation products: foldable displays as well as chips of 7 nanometer line-widths or less that’re made via the so-called extreme ultra-violet (EUV) process. That puts at risk Samsung’s express goal of investing $116 billion to become the No.1 in the logic chip business by 2030. Without Japan’s materials, Samsung may be hamstrung in efforts to develop an EUV-based foundry business and in advanced memory chipmaking.

Their rivals may step in to fill that gap in the interim. Micron Technology Inc., the only other memory chip maker of significance, stands to benefit. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. could further widen its lead over Samsung when it comes to made-to-order chips, vying for Samsung customers like Qualcomm Inc. and Nvidia Corp.

“There will be considerable impact on both sides,” said Heungchong Kim, a senior research fellow at the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy. “Those materials are not something that can be replaced in a short period. This is becoming a weird situation.”

The situation may worsen if Japan removes South Korea from a so-called “White List” of countries treated as presenting no risk of weapons proliferation, a move Tokyo is now considering.

Japan and Korea have traditionally turned to the U.S. to mediate in their clashes, but it’s unclear this time if Trump is keen to step into the fray. Compounding the situation are the basic mechanics of the restrictions. While not a ban per se, would-be exporters of the affected materials need to obtain a license from the government. That could take up to 90 days — an eternity for a fast-moving industry.

There’s also disagreement by industry analysts over which corporations exactly will get hit hardest, in part because some Japanese firms have either localized production in South Korea or maintain plants in countries such as China.

Japan’s Sumitomo Chemical Co. is a key supplier of polyimides, according to Taipei-based WitsView and Isaiah Research — but company representatives deny it makes the material. IHS Markit analyst David Hsieh said in addition to Sumitomo Chemical, SKC — like Hynix, an affiliate of the giant SK Group — or Kolon Industries are viable local substitutes.

JSR is a major resist producer, while the global hydrogen fluoride market is dominated by Kanto Denka Kogyo Co., Showa Denko KK and Daikin Industries Ltd., according to Taipei-based Isaiah Research. Resist manufacturer Tokyo Ohka Kogyo Co. said it already supplies South Korean customers locally. Daikin said the restrictions will have no impact on its hydrogen fluoride because the materials are made in China, while Morita Chemical Industries Co. is building a plant there that will go online next year.

“While high levels of semiconductor inventory might provide some cushion, time may not be on Korea’s side,” Citigroup economists Jin-Wook Kim and Johanna Chua said in a recent note. “Displacing Korean chips would disrupt the supply chain because building alternative sources needs specific technology and sizable capex.”

(Updates with company shares from fourth paragraph.)

–With assistance from Heejin Kim, Yuki Furukawa and Isabel Reynolds.

To contact the reporters on this story: Sohee Kim in Seoul at [email protected];Debby Wu in Taipei at [email protected];Pavel Alpeyev in Tokyo at [email protected]

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tom Giles at [email protected], Edwin Chan, Colum Murphy

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com” data-reactid=”70″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.