(Bloomberg Opinion) — If you’re in the business of selling passenger aircraft, design flaws that might cause your planes to crash ought to be non-existent.

That’s why the discovery of a second critical safety risk on Boeing Co.’s 737 Max is so alarming. Tests by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration found that flight computers could cause the plane to dive in a way that pilots struggled to correct in simulator tests, people familiar with the finding told Alan Levin and Julie Johnsson of Bloomberg News on Wednesday. The problem wasn’t connected to the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, that’s been linked to 737 Max crashes in Indonesia and Ethiopia, but could produce similar effects, one of the people said.(1)

Lightning shouldn’t strike in the same place twice. Developing new aircraft is a decade-scale project, with certification by aviation regulators alone typically taking five years. By the time a plane is ready to be delivered to customers, it should have passed through such a stringent battery of tests that only once-in-a-lifetime events can cause problems.

It’s bad enough that the 737 Max made it onto the market with one system that could cause uncontrolled flights to plunge into the ground. To discover a second casts a worrying light on the company’s entire safety culture.

How could Boeing have allowed further problems in such critical systems to lie undisclosed?

Since the 737 Max grounding, many people, including this columnist, have exhorted the company to follow the crisis-management approach taken by Johnson & Johnson in the wake of the 1982 Tylenol scandal: Put safety first and maximize transparency to convince the public that the company has nothing to hide.

And yet, as my colleague Brooke Sutherland has argued, there’s precious little evidence that Boeing has done enough in terms of improving transparency, communication and oversight to get it out of the doghouse.

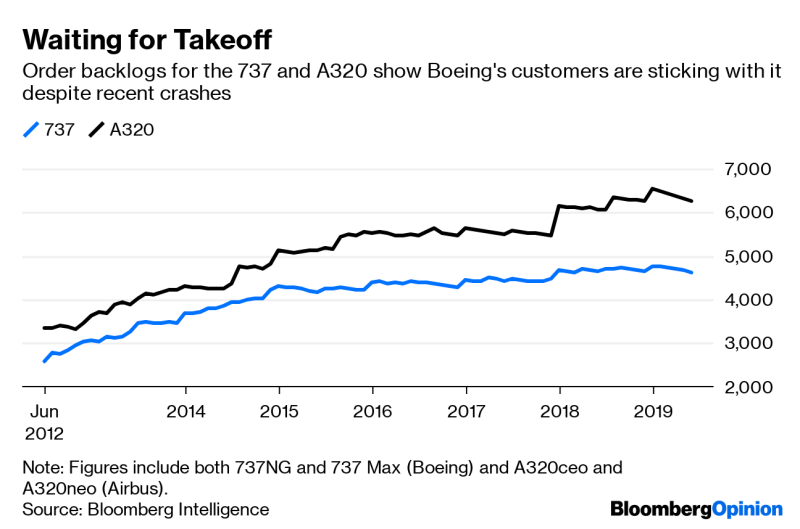

The problem is that Boeing is a different sort of company than Johnson & Johnson. Consumers were easily able to choose another brand of painkillers if they didn’t trust Tylenol, so winning back their trust was an existential issue. The same doesn’t apply in the case of commercial aircraft, which are sold in a duopolistic market where any airline wanting to get a good price from Airbus SE has to keep Boeing in play as a potential supplier.

In theory, passengers who refuse to fly on the 737 Max and find out at the departure gate that their aircraft has been switched from an A320neo could tear up their tickets and exercise consumer choice in the same way as a shopper buying headache pills. In practice, we’re all stuck with whatever is served up to us.

Investors seem to know this. Boeing’s share price, amid the grounding of its key product and a simmering trade war over one of its biggest markets, is doing just fine. Blended forward 12-month price-earnings ratios put it on a higher valuation than Facebook Inc., Alphabet Inc., and Apple Inc. At the Paris airshow this month, the company managed to score a haul of around $34 billion in new orders – less than the $44 billion tally for Airbus, to be sure, but grounded on a $24 billion commitment from IAG SA for the 737 Max itself.

Chief Executive Officer Dennis Muilenburg this week promised to inspire a “relentless pursuit of safety” at Boeing. “We want to create an environment where everyone feels comfortable bringing problems to the surface,” he told the Aspen Ideas Festival on Wednesday. “We don’t want to create an environment where problems stay hidden.”

This latest revelation suggests that’s still not happening – and far from suffering, Boeing is doing just fine.

(1) Slow processing by a cockpit chip meant that the workarounds pilots use to recover from problems with the MCAS were taking too long to kick in, according to a separate report by Aviation Week. Boeing acknowledged the issue and said it’s working on a software fix.

To contact the author of this story: David Fickling at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”58″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.