(Bloomberg Opinion) — The ability of the world’s biggest sports competitions to keep making more money could depend on one relatively mundane factor: broadband networks’ capacity to live-stream games to millions of households.

The biggest test so far will come this week with Amazon.com Inc.’s broadcast of 10 Premier League matches. The broadcast revenues from England’s flagship soccer competition have started to plateau as television stations grow wary about writing outsize checks to obtain the rights. In response, the league has solicited U.S. tech giants in an effort to reinvigorate the bidding war for rights.

Their entreaties have so far largely fallen on deaf ears. That is, until Amazon agreed to buy a relatively small package of Premier League games in June 2018. But Amazon’s interest fell short of creating a bidding war. The e-commerce giant is understood to have paid very little for the privilege of streaming 10 games this week and another 10 after Christmas. The intention was instead to whet Amazon’s appetite. If the broadcasts prove successful — which in Amazon’s case means signing up a host of new subscribers for its Prime service — then it might encourage the Seattle-based firm to bid for the bigger packages of games currently held by Comcast Corp.’s Sky division and BT Group Plc.

The timing of the games is of course opportune for Amazon, coming shortly before Christmas. When users sign up for Prime Video, the service that will broadcast the games, they will also get access to the broader suite of Prime offerings, including Prime Delivery, which promises faster and free deliveries of products bought via Amazon.com. Prime subscribers spend an average of $1,400 a year on the website, compared to the $600 of other customers, the research firm Consumer Intelligence Research Partners estimated last year.

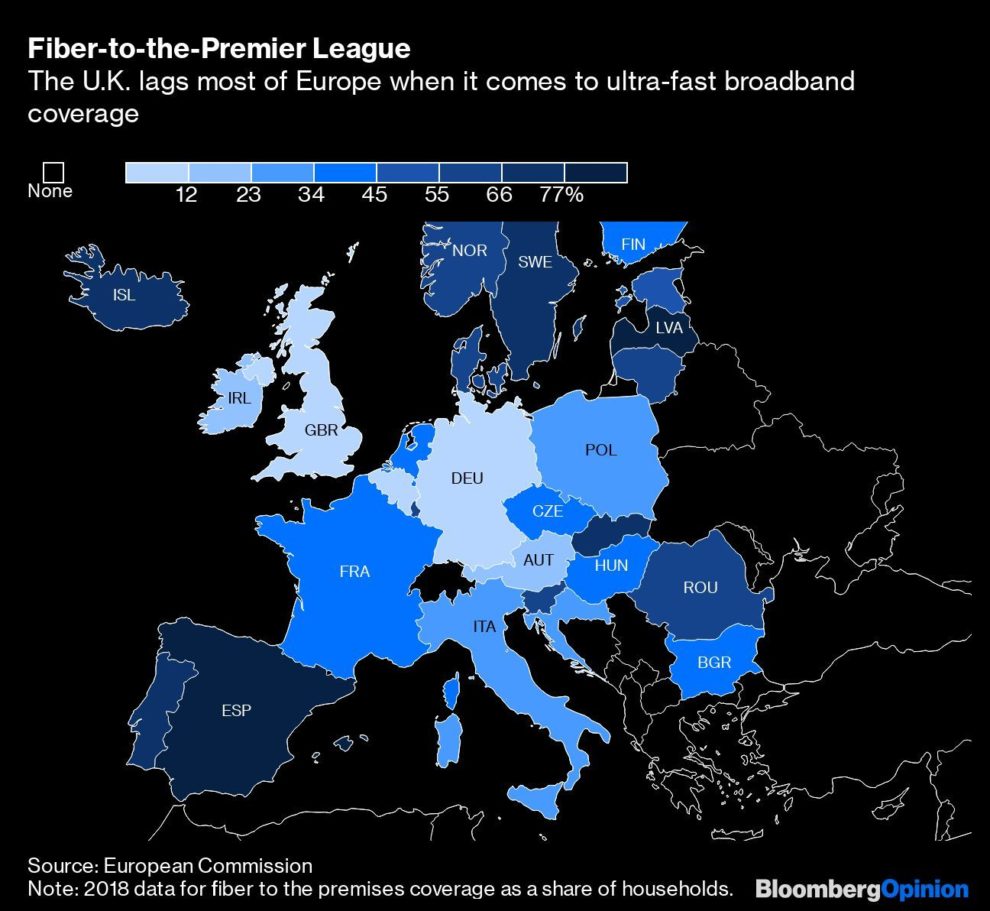

The challenge for Amazon is that it will be largely dependent on the U.K.’s broadband infrastructure to distribute the games, and that network is not fundamentally designed to support video live-streaming. While it has subcontracted BT to supply the feed to pubs and bars, ordinary households will use their existing internet connections. That may not make for pretty viewing as the U.K. has the fourth-lowest penetration of fiber-optic broadband in the European Union.

Prior experiences have surfaced a welter of problems. Amazon’s first foray into sports broadcasting in the U.K. prompted a slew of complaints, partly to do with the editorial standards, but also to do with picture quality, a far more significant concern given the scale of the Premier League soccer challenge. YouTube TV’s live-stream of last year’s World Cup semi-final between England and Croatia crashed in the U.S., and AT&T Inc. ended up providing a pay-per-view golf match between Tiger Woods and Phil Mickelson free after experiencing glitches. And while Amazon has shown National Football League games, the rights were shared with other classic broadcasters, reducing the network demand.

An examination of the Premier League’s viewership highlights the extent of the risks. A match in August 2018 between Manchester United and Leicester City attracted some 1.1 million viewers on Sky, according to the Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board. Just 72,000 of those watched the game via a mobile device — the most readily available proxy for live-streaming. Even the England-Croatia game drew in just 337,000 viewers using mobile devices. On Dec. 4, Amazon will concurrently broadcast six games, each of which could have several hundred thousand viewers.

Top of the list will be Liverpool versus Everton — a derby game of two sides from the same city, and therefore likely to create a demand peak in a relatively concentrated area. The match kicks off 45 minutes after the others, which could be construed as a move to try to spread the demand on the network.

There are ways Amazon, with its deep cloud-computing expertise, can alleviate potential problems, not least by leaning on other content delivery network specialists such as Akamai Technologies Inc., whose additional servers can make it easier to handle peaks of demand. But even if the picture quality is up-to-scratch, there is always likely to be a lag which could prompt complaints. When Twitter Inc. broadcast NFL games in 2016, a 30- to 90-second lag meant that viewers often saw the score in a tweet before watching the play itself.

It is easier for Amazon to justify spending more to deliver the content than it will generate from the subscriptions themselves, because it will make more money in the long-term from customers buying more products from Amazon.com. But if things go badly wrong, then it will play into the hands of Sky and BT, who have years of experience with live sports broadcasting, and control much of the underlying network.

If there’s no big uptick in subscribers for Amazon this time around, and the games are beset by technical snafus, that’ll make it harder to attract more viewers — and thus more subscribers to Prime Video — over the next two years for which it has the rights. That could end hopes that Amazon or any other tech giant will be willing to bid serious money for the games anytime soon.

To contact the author of this story: Alex Webb at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe’s technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”63″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.