Hundreds of Android apps, far more than previously disclosed, have sent granular user location data to X-Mode, a data broker known to sell location data to U.S. military contractors.

The apps include messaging apps, a free video and file converter, several dating sites, and religion and prayer apps — each accounting for tens of millions of downloads to date, according to new research.

Sean O’Brien, principal researcher at ExpressVPN Digital Security Lab, and Esther Onfroy, co-founder of the Defensive Lab Agency, found close to 200 Android apps that at some point over the past year contained X-Mode tracking code.

Some of the apps were still sending location data to X-Mode as recently as December when Apple and Google told developers to remove X-Mode from their apps or face a ban from the app stores.

But weeks after the ban took effect, one popular U.S. transit map app that had been installed hundreds of thousands of times was still downloadable from Google Play even though it was still sending location data to X-Mode.

The new research, now published, is believed to be the broadest review to date of apps that collaborate with X-Mode, one of dozens of companies in a multibillion-dollar industry that buys and sells access to the location data collected from ordinary phone apps, often for the purposes of serving targeted advertising.

But X-Mode has faced greater scrutiny for its connections to government work, amid fresh reports that U.S. intelligence bought access to commercial location data to search for Americans’ past movements without first obtaining a warrant.

X-Mode pays app developers to include its tracking code, known as a software development kit, or SDK, in exchange for collecting and handing over the user’s location data. Users opt-in to this tracking by accepting the app’s terms of use and privacy policies. But not all apps that use X-Mode disclose to their users that their location data may end up with the data broker or is sold to military contractors.

X-Mode’s ties to military contractors (and by extension the U.S. military) was first disclosed by Motherboard, which first reported that a popular prayer app with more than 98 million downloads worldwide sent granular movement data to X-Mode.

In November, Motherboard found that another previously unreported Muslim prayer app called Qibla Compass sent data to X-Mode. O’Brien’s findings corroborate that and also point to several more Muslim-focused apps as containing X-Mode. By conducting network traffic analysis, Motherboard verified that at least three of those apps did at some point send location data to X-Mode, although none of the versions currently on Google Play do so. You can read Motherboard’s full story here.

X-Mode’s chief executive Josh Anton told CNN last year that the data broker tracks 25 million devices in the U.S., and told Motherboard its SDK had been used in about 400 apps.

In a statement to TechCrunch, Anton said:

“The ban on X-Mode’s SDK has broader ecosystem implications considering X-Mode collected similar mobile app data as most advertising SDKs. Apple and Google have set the precedent that they can determine private enterprises’ ability to collect and use mobile app data even when a majority of our publishers had secondary consent for the collection and use of location data.

We’ve recently sent a letter to Apple and Google to understand how we can best resolve this issue together so that we can both continue to use location data to save lives and continue to power the tech communities’ ability to build location-based products. We believe it’s important to ensure that Apple and Google hold X-Mode to the same standard they hold upon themselves when it comes to the collection and use of location data.”

The researchers also published new endpoints that apps using X-Mode’s SDK are known to communicate with, which O’Brien said he hoped would help others discover which apps are sending — or have historically sent — users’ location data to X-Mode.

“We hope consumers can identify if they’re the target of one of these location trackers and, more importantly, demand that this spying end. We want researchers to build off of our findings in the public interest, helping to shine light on these threats to privacy, security, and rights,” said O’Brien.

TechCrunch analyzed the network traffic on about two-dozen of the most downloaded Android apps in the researchers’ findings to look for apps that were communicating with any of the known X-Mode endpoints, and confirmed that several of the apps were at some point sending location data to X-Mode.

We also used the endpoints identified by the researchers to look for other popular apps that may have communicated with X-Mode.

At least one app identified by TechCrunch slipped through Google’s app store ban.

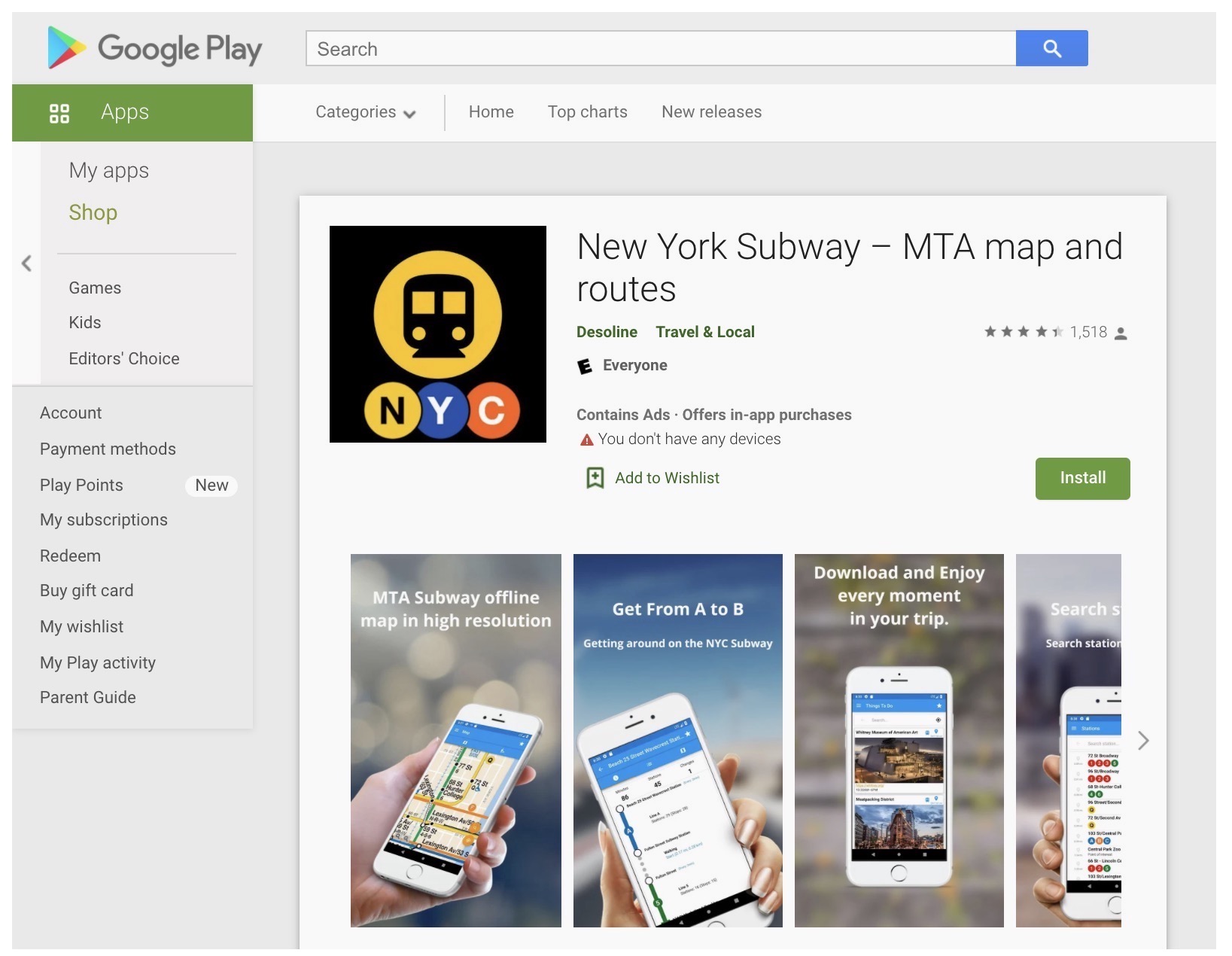

New York Subway in Google Play., until it was removed by Google. (Image: TechCrunch)

New York Subway, a popular app for navigating the New York City subway system that has been downloaded 250,000 times, according to data provided by Sensor Tower, was still listed in Google Play as of this week. But the app, which had not been updated since the app store bans were implemented, was still sending location data to X-Mode.

As soon as the app loads, a splash screen immediately asks for the user’s consent to send data to X-Mode for ads, analytics and market research, but the app did not mention X-Mode’s government work.

Desoline, the Israel-based app maker, did not respond to multiple requests for comment, but removed references to X-Mode from its privacy policy a short while after we reached out. At the time of writing, the app has not returned to Google Play.

A Google spokesperson confirmed the company removed the app from Google Play.

Using the researchers’ list of apps, TechCrunch also found that previous versions of two highly popular apps, Moco and Video MP3 Converter, which account for more than 115 million downloads to date, are still sending user location data to X-Mode. That poses a privacy risk to users who install Android apps from outside Google Play, and those who are running older apps that are still sending data to X-Mode.

Neither app maker responded to a request for comment. Google would not say if it had removed any other apps for similar violations or what measures it would take, if any, to protect users running older app versions that are still sending location data to X-Mode.

None of the corresponding and namesake apps for Apple’s iOS that we tested appeared to communicate with X-Mode’s endpoints. When reached, Apple declined to say if it had blocked any apps after its ban went into effect.

Read more on TechCrunch

“The sensors in smartphones provide rich data that can be exploited to limit our movements, our free expression, and our autonomy,” said O’Brien. “Location spying poses a serious threat to human rights because it peers into the most sensitive aspects of our lives and who we associate with.”

The newly published research is likely to bring fresh scrutiny to how ordinary smartphone apps are harvesting and selling vast amounts of personal data on millions of Americans, often without the user’s explicit consent.

Several federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service and Homeland Security, are under investigation by government watchdogs for buying and using location data from various data brokers without first obtaining a warrant. Last week it emerged that intelligence analysts at the Defense Intelligence Agency buy access to commercial databases of Americans’ location data.

Critics say the government is exploiting a loophole in a 2018 Supreme Court ruling, which stopped law enforcement from obtaining cell phone location data directly from the cell carriers without a warrant.

Now the government says it doesn’t believe it needs a warrant for what it can buy directly from brokers.

Sen. Ron Wyden, a vocal privacy critic whose office has been investigating the data broker industry, previously drafted legislation that would grant the Federal Trade Commission new powers to regulate and fine data brokers.

“Americans are sick of learning that their location data is being sold by data brokers to anyone with a credit card. Industry self-regulation clearly isn’t working — Congress needs to pass tough legislation, like my Mind Your Own Business Act, to give consumers effective tools to prevent their data being sold and to give the FTC the power to hold companies accountable when they violate Americans’ privacy,” said Wyden.

Send tips securely over Signal and WhatsApp to +1 646-755-8849. You can also send files or documents with SecureDrop.