CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — The stock market will rally between now and the end of the year.

But that doesn’t mean there will be the “year-end rally” that many advisers have begun telling their clients to expect.

This is an important distinction because the advisers who have been forecasting such a rally have something in mind that is above and beyond the trivial truth that the market will at some point and to some extent rally. And although these advisers don’t bother to precisely define their “year-end rally,” none of the definitions I have analyzed stands up to historical scrutiny.

I acknowledge, however, that it makes a certain amount of sense that the year-end period would be special on Wall Street. It’s when money managers begin thinking about how they will want to window-dress their portfolios for their year-end reports, when investors engage in tax-loss selling in order to shelter capital gains on which they would otherwise have to pay taxes, and when retailers pull out all the stops in order to have as good as possible year-end holiday shopping season.

Some even think the so-called Santa Claus Rally begins in late October, just like those shameless marketers who put up their Christmas decorations before Halloween.

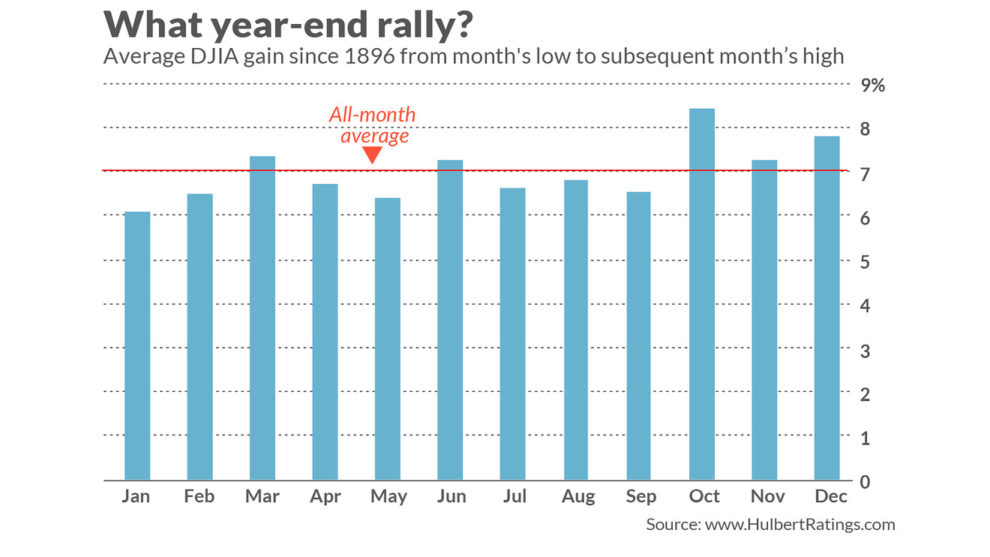

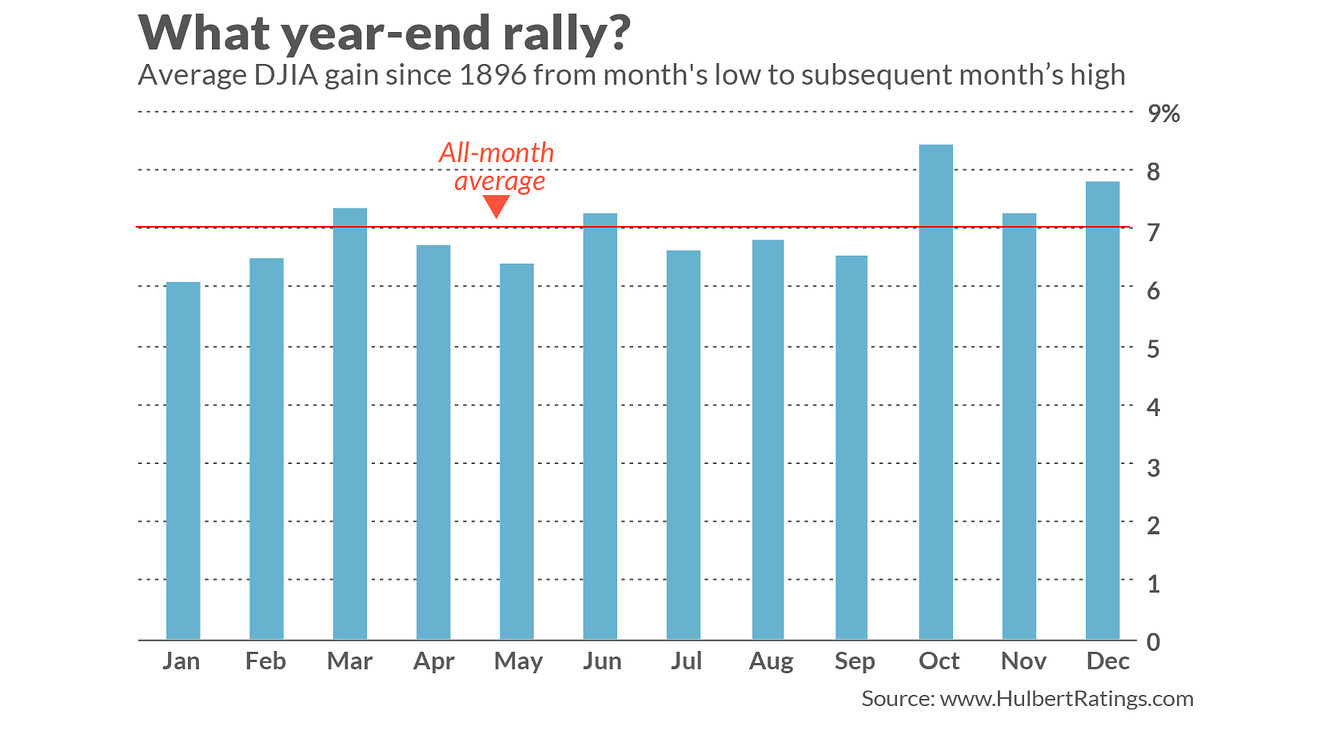

Nevertheless, however plausible it is that the stock market should exhibit a year-end rally, it fails to show up in the historical record. Consider the stock market’s gain from November’s low to December’s high. This is the definition of a year-end rally that will produce the greatest possible gain, of course. So if there is a year-end rally, it at a minimum should show up when defined in this way.

And it very much appears to be. On average since 1896, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.09% was created, the average DJIA year-end rally defined in this way has been 7.2%.

To be sure, you’d need perfect foresight to capture that gain, since only after the fact do we know when November registers its low and its December high. Still, this rally potential certainly seems noteworthy: On an annualized basis, it’s equivalent to a gain of over 50%. If the stock market were to rally this much this year, and assuming November’s low is no lower than where it stands today, the DJIA would trade nearly as high as 29,000 in December.

In fact, however, this 7.2% average year-end rally is no better than what shows up in any other two-month period of the calendar. To show this, I calculated the equivalent rally potential for every other month of the year. Those other 11 months’ average rally potential has been 7.0%. (See chart.) Given the variability in the data, November’s rally potential is statistically indistinguishable from that of the other 11 months.

What about years like this one in which the stock market’s year-to-date gains are particularly strong? We could easily imagine that the year-end rally potential in such years would be below average, given that advisers and institutional investors would have the incentive to lock in their gains.

The data don’t support that hunch, however. Over the last century, the year-end rally actually has been slightly greater in years with stronger year-to-date gains through October — though, once again, the difference is not significant at the 95% confidence level that statisticians often use when determining if a pattern is genuine.

Read: Here’s how the stock market tends to trade in the rest of the year after an ugly October start

Note carefully that these results do not mean that the stock market will fall between now and the end of the year. It very well may rally, of course. But if it does, it will not be because the next two months are the last two of 2019 — but because of entirely mundane reasons like earnings coming in better than expected, a resolution of the trade war and the like.

Read: Three company earnings reports that are better than you thought — and three that are worse

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected].