How you ask a question has a huge impact on the answer.

This truth is already widely known in fields other than retirement finance, of course. A famous example comes from Dan Ariely, a professor psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University: Participation in organ donation programs varies widely according to how the question is worded. If you ask people if they want to opt into such programs, few do so. But if you automatically sign them up and then allow them to opt out, most people end up participating.

New research has found something similar when it comes to retirement finance. How a deceptively simple question gets asked can lead to an improvement in retirement wealth of up to 50%, according to the authors of the just-published study.

The study is “Target Date Funds and Portfolio Choice in 401(k) Plans,” which recently began being circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Its authors are Olivia Mitchell (who holds two professorships at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania: Business Economics and Public Policy, and Insurance and Risk Management) and Stephen Utkus, principal and director of Vanguard’s Center for Investor Research.

The deceptively minor change that has such a huge consequence, the researchers found, boils in effect down to whether participants in a 401(k) plan are asked whether they want to opt in or opt out of a target-date fund. The researchers were able to study this change by analyzing the fund choices made in the 401(k) accounts managed by Vanguard. (For the record, the data were scrubbed to remove any personal details.)

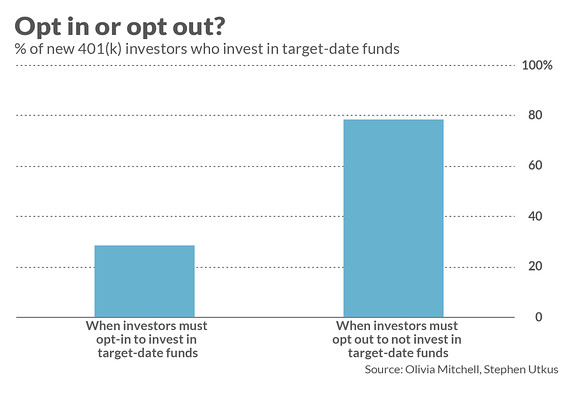

What the researchers founds is summarized in the chart below:

• When new entrants into a 401(k) program had to opt in (proactively pick a target-date fund out of the large number of mutual funds that are offered), just 28.4% invested in a target-date fund.

• When new entrants were automatically enrolled in the target-date funds corresponding to their anticipated retirement ages, and required to opt out if they wished not to invest in such funds, 78.7% invested in them.

The researchers next examined the consequences of this difference for investors’ asset allocations. They found a big increase in equity exposure—by as much as 24 percentage points—for this second group, which I will call the “opt-out” investors. Over a 30-year horizon, this increase “could raise expected retirement wealth by as much as 50%,” they calculated.

This increase in retirement wealth may puzzle many of you. Why should an investor who avoids target-date funds have lower equity exposure than one who doesn’t? After all, there is nothing preventing the investor who shuns target-date funds from choosing others that are just as exposed to equities, if not more so.

The answer to this puzzle goes back to the psychology of opting in versus opting out. Consider the thought process we typically go through when presented with the dizzyingly large array of possible investments that the typical 401(k) offers—an array that will only grow as more 401(k) plans allow investments in ETFs as well as open-end mutual funds. Overwhelmed by this many options, it’s difficult for us to decide to become fully invested in equities.

It’s just too risky, we tell ourselves. We’d never forgive ourselves if we chose to allocate 100% of our 401(k) accounts to equities right as a severe bear market were to begin. (Behavioral economists’ study of this is known as regret theory.)

A related psychological dynamic is what I call “analysis paralysis:” Upon studying a strategy long and hard enough, we can poke holes in it, and target-date funds are no exception. For example, why assume that, if I am retiring in 2030, my retirement goals are identical to all others who are retiring that year? And if I don’t, then why should I believe that a “target-date 2030 fund” might not be ideal for me.

These are perfectly legitimate objections, of course. But if analysis paralysis leads us to do nothing, or to be too conservative during the accumulation phases of our retirement financial planning, then asking these questions will have done more harm than good.

In other words, the perfect can be the enemy of the good.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. Hulbert can be reached at [email protected].

div > iframe { width: 100% !important; min-width: 300px; max-width: 800px; } ]]>