Financial-services companies began to reduce monetary settlements to consumers assumed to be Black or lower-income as soon as Donald Trump became president, according to a working paper published Thursday.

The paper, from two Boston College researchers, tracked consumer complaints, and the follow-ups recorded by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, a government agency created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Their findings show that in January 2017 — even before President Trump made any changes to the bureau — consumers from predominantly Black or lower-income ZIP codes who complained about financial-services companies were disproportionately less likely to receive monetary relief than disputes lodged from white-majority ZIP codes.

The unequal results suggest the financial industry assumed the Trump administration would take a more hands-off approach to regulation, and that some company practices were adjusted in ways that denied monetary relief to borrowers they considered to be less-desirable consumers.

“Under the Obama administration, consumers from all backgrounds were equally likely to benefit from the CFPB’s program to give consumers restitution for the issues they had with financial services providers,” said Rawley Heimer, a professor at Boston College and lead author on the report. “That changed dramatically under the Trump administration. Consumers became less likely to receive restitution, with the effects felt especially hard among consumers from low socioeconomic backgrounds and Black Americans.”

MarketWatch provided the CFPB with an overview of the paper’s findings prior to its publication on Thursday, and a link once the paper was public. In response to requests for comment, a CFPB spokesperson said, “Unfortunately, the Bureau has not had an opportunity to review the findings of the forthcoming paper; therefore, it is unable to offer comment at this time about its conclusions.”

Fair-lending laws prohibit discrimination against consumers based on race or other factors, like geographical location, but financial-services firms use technology in their credit decisions and to personalize their interactions with consumers, a capability that can work in consumers’ favor or against them, as in this case.

Out of the ashes of crisis

Disparate treatment for Black Americans in the financial services arena isn’t new. But the uneven financial relief takes on a special resonance in the wake of the highly visible police violence against Black people that kindled outrage and civil disobedience throughout the summer of 2020, even as minorities and other vulnerable groups took a disproportionate hit from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among other things, Blacks lost more than any other demographic group in the wake of the subprime crisis, and now, amid the lowest mortgage rates in history, aren’t taking advantage to refinance, new Federal Reserve research shows.

Complex mortgages, exotic financial products and lax consumer protections all played a role in creating the 2008 global financial crisis. As a result, millions of homes and trillions of dollars of home equity were lost. In the wake of the crisis, the CFPB was founded to try to provide a single point of contact for consumers in the financial marketplace.

During the Obama administration, the bureau created new mortgage standards meant to make home loans safer and easier for borrowers to understand. It also extracted billions of dollars in fines from subprime lenders. But the CFPB’s powers were curtailed under Trump’s pick Mick Mulvaney, as the bureau’s acting director, including in the booming area of subprime auto lending, according to various reports.

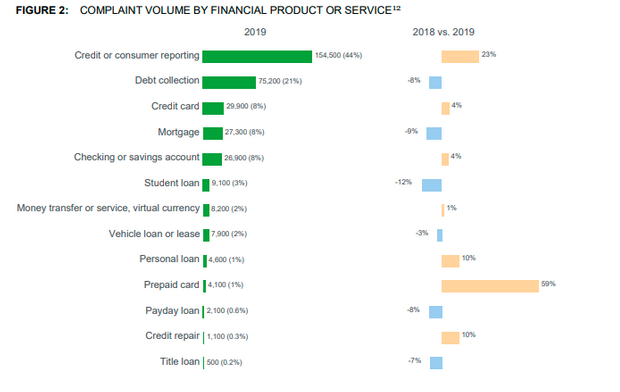

The CFPB created its consumer complaint database to help consumers fix financial problems, and it has collected thousands of complaints each year — 352,400 of them in 2019 — on every type of financial product, from credit reports to auto loans to money transfers.

The bureau forwards most consumer complaints it receives to the company named in the dispute, and it records company responses in one of a few categories: “closed with monetary relief,” “closed with non-monetary relief,” “closed with explanation,” “in progress,” and some other administrative options.

The paper, written by Heimer and a co-author, Charlotte Haendler, focused on complaints in the first category, “closed with monetary relief.” On average, approximately 5% of consumers received financial restitution, they find, under both the Obama and Trump administrations. What’s more, consumers who live in low socioeconomic ZIP codes are just as likely to file complaints as those in higher-income areas.

“The Obama administration seemed interested in supporting the interests of consumers from low socio-economic backgrounds, but with a different political regime that doesn’t share that view, there’s a change in terms of who the winners and losers are,” Heimer told MarketWatch. “The private market responds to expectations about that as well. When companies know that they have a weak regulator, they know they can act in a way that’s beneficial to their bottom line, not to consumers.”

“ Consumers who live in low socioeconomic ZIP codes are just as likely to file complaints as those in higher-income areas, but the poor and Black Americans receive less relief. ”

But starting in 2017 — even before Trump had time to install his choice for CFPB director at the agency — complaints filed from consumers in ZIP codes defined as lower-income, and those identified as being home to more Black Americans, were less likely to get monetary relief.

That’s a shift from the origins of the CFPB, which Congress established in 2010 with a director who would presumably have independent tenure protections to avoid conflicts of interest. The Supreme Court in 2020 found that structure unconstitutional, leaving the agency fully operational but also making a director removable at will by the U.S. president and subject to partisan control, according to Pratin Vallabhaneni, a partner at law firm White & Case.

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, whose university research led to her proposing the idea that eventually became the CFPB, told MarketWatch that the bureau has become politicized.

“For several years, the Trump administration has undermined the CFPB, tossing out important consumer protections and refusing to enforce the law, often at the expense of Black and brown Americans and low-income communities that are disproportionately targeted by greedy companies and lenders,” Warren said. “I look forward to working with the incoming Biden-Harris administration on ensuring that the CFPB once again stands up for American consumers.”

Bureau for the people?

Several consumer advocates called the academic paper’s findings disturbing, and said it points to the need for more research, as well as more vigilance from the CFPB.

“I think the discrepancies (in the report) are very troubling and suggest that the incoming CFPB should really double down on analyzing its own data to be sure consumers are getting good treatment across the board regardless of product or demographics,” said Gail Hillebrand, a longtime consumer advocate associated with the CFPB during the Obama administration.

What’s particularly troubling is the signal the industry appears to have received about what they could expect from a consumer bureau under an antiregulation president, Hillebrand told MarketWatch.

“Some people will get good customer service because of who they’re banking with or how much money they keep in their accounts,” she said. “But every American needs to have an active financial services regulator in the job. The industry needs to know that the regulator is going to put consumers first and pay attention to their problems.”

The paper studied complaints filed with the CFPB between January 2014 and March 2020, meaning its findings preceded the bulk of the disputes flagged by consumers reeling from the shocks of the coronavirus pandemic, including the spring of 2020 when some 25 million-30 million people were put out of work almost overnight.

While the next step for the working paper will be a peer review process, its findings will be watched closely by consumer advocates, including those focused on equitable treatment in the financial marketplace.

“This study reveals that the law is being implemented in such a way that harm to Black consumers is not being treated as seriously as harm to others,” said Jennifer Taub, a professor at Western New England University School of Law and author of Big Dirty Money. “What’s hard to know based on this research is whether it’s intentional or not.”

Regardless, Taub said in an interview, anti-discrimination laws don’t just focus on what consumer advocates call “disparate treatment,” but also the impact of treatment that may be harmful even if it’s not necessarily intentional, a condition called “disparate impact.”

“ ‘What’s hard to know based on this research is whether it’s intentional or not.’ ”

“What concerns me is that it took an outside researcher to find this,” Taub said.

In fact, the disparate treatment/disparate impact issue was one of the research questions that drew Heimer to this study. If the CFPB was doing its job, there shouldn’t be any differences in consumer outcomes, no matter what the demographics, he noted.

“The CFPB should be leveling the playing field,” he said in an interview. “The key feature to keep in mind is that a broad selection of financial service providers feels more comfortable applying disparate treatments in a political environment when they know the CFPB is going to be less aggressive toward them.”

One of the ironies of the Trump-era consumer environment that the paper highlights is that it’s in the best interest of everyone, including higher socioeconomic consumers and corporations, to be as accommodating as possible to all consumers, sources stressed.

“ ‘There’s no reason why, say, a credit-card provider can’t make reasonable revenues from customers that aren’t being tricked by shady terms. But when they have to compete with companies that get revenues by ripping customers off, no one’s a winner.’ ”

“Under a weaker CFPB, the bottom-feeding, low-productivity financial services providers are the ones more likely to win, whereas providing valuable services for consumers, helping them get stable financial products, becomes less of a winning formula for companies,” Heimer said. “There’s no reason why, say, a credit-card provider can’t make reasonable revenues from customers that aren’t being tricked by shady terms. But when they have to compete with companies that get revenues by ripping customers off, no one’s a winner.”

For Jennifer Taub, the questions raised by the paper evoke another case that’s regarded as a CFPB success: missteps at Wells Fargo WFC, -7.80%.

For years, the bank pressured employees to open accounts and add services for customers that they didn’t request and may not have needed, including car insurance premiums. Thousands of the bank’s customers had their cars repossessed when they didn’t pay for the insurance they didn’t realize they had signed on for, including many members of the military. That misstep against a protected class of consumer wound up costing Wells even more in fines and bad PR.

“Any business should have in place checks to guard against what may seem like discriminatory intent that can impact peoples’ lives,” Taub said.

“The efforts to help level the playing field for consumers who have less market power can only go so far as the political will to do so,” Heimer said. “When there are really concerted efforts to help disadvantaged consumers, they can be successful but when that support falls, consumers are left on their own and they may lack recourse.”

Joy Wiltermuth contributed to this article

Add Comment