The Federal Reserve’s most recent monetary stimulus spree has expanded its balance sheet to near its all-time high of $4.5 trillion set in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008.

The Fed added almost $400 billion in recent months to keep credit flowing by means of short-term “repo” operations and outright purchases of U.S.Treasury bills which pushed its balance sheet at year-end to about $4.2 trillion.

Yet, even with the New York Fed vowing to keep credit spigots open “just as long as they are needed,” analysts expect its prior balance sheet high seen in 2015 will be eclipsed only after many more months of expansion.

Here are three reasons why.

It’s not only repos

The Fed’s balance sheet was shrinking after it stopped buying longer-duration Treasury debt and mortgage bonds in 2017 but worries about economic growth in the wake of President Trump’s trade war with China brought an end to the run off program in August last year.

Cash reserves held at the Fed on behalf of banks fell last year too, sinking to a seven-year low of about $1.45 trillion in September from $2.37 trillion two years prior, around when the central bank started to taper its portfolio.

‘The interventions were basically to regain control over the price of money.’

Mark Cabana, head of U.S. interest rates strategy at Bank of America Global Research, was early to predict coming funding tumult. Cabana said in August last year that a deluge of Treasury bond issuance to fund the U.S. federal government’s deficit may mean financial institutions would run out of cash to fund the debt in the short term.

In September last year, the Fed was indeed caught off guard when overnight funding rates in the short term money markets, or “repo” market, spiked to nearly 10% from about 2%, forcing the central bank to start offering daily cash facilities to keep short-term rates low. The Fed also started buying Treasury bills at a $60 billion monthly clip in October to boost bank cash reserves, with a plan to extend these purchases through at least the second quarter of 2020.

“The interventions were basically to regain control over the price of money,” said Lyn Alden, founder of Lyn Alden Investment Strategy in an interview with MarketWatch.

“If they had not intervened, the repo rate probably would have stayed in the double-digits, which could have spread to the Treasury market.”

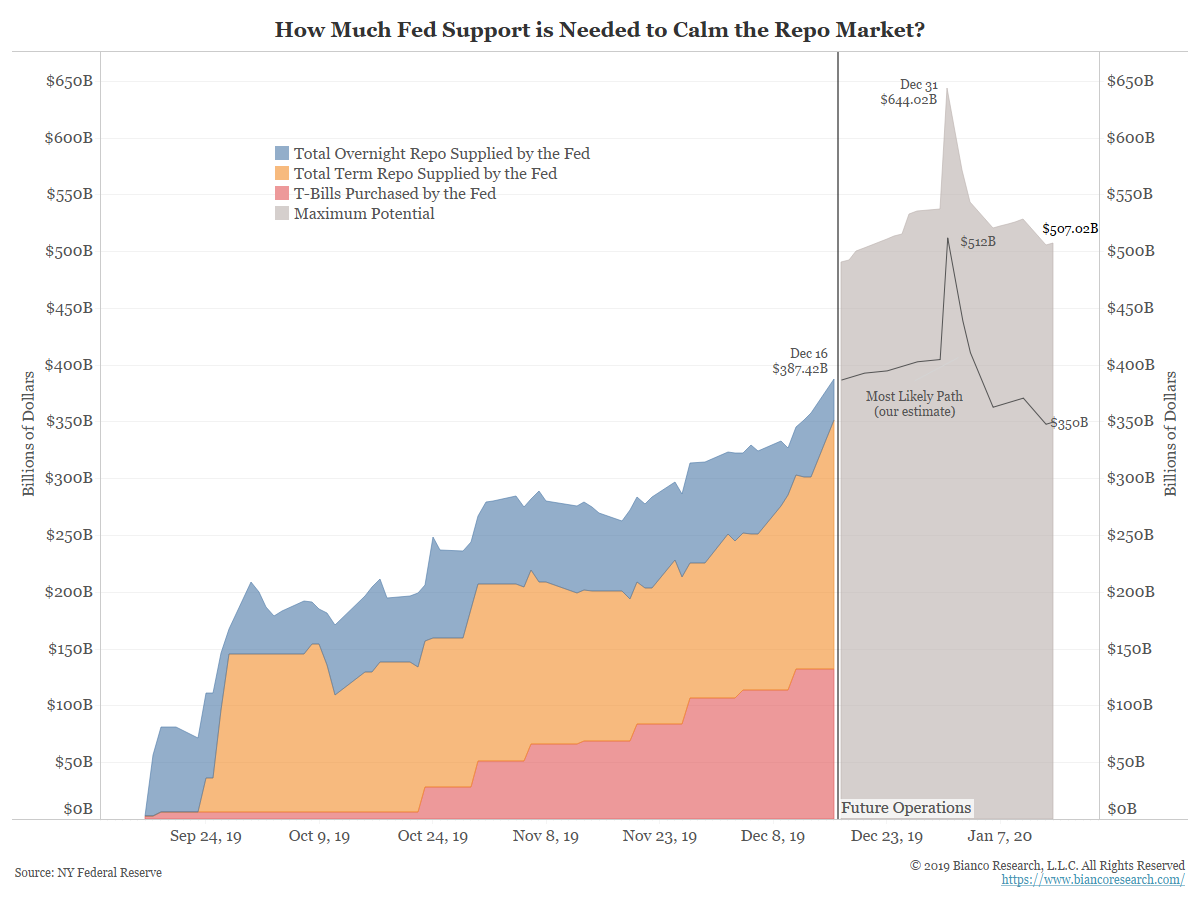

Here’s a chart from Bianco Research showing what the Fed’s balance sheet could look like in the coming months.

Bianco Research

Bianco Research Fed’s two-pronged approach

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell insisted in an October speech that the current balance sheet expansion is for managing reserves, not a return to the large-scale asset-purchases launched a decade ago to shore up an American economy in crisis.

Going forward, the central bank is expected to embark on a two-pronged plan to keep cash reserves elevated in the banking system, but also to reduce the amount of reserves hoarded by major banks.

See: Dimon says money-market turmoil last month risks morphing into a crisis if Fed falters

“It is very likely that, in 2020, the Fed will take steps to make banks increasingly indifferent between holding reserves and Treasury securities,” wrote a BCA Research team led by Ryan Swift, in a recent report.

Ultimately, much depends on how quickly the Fed gets to a reserve level it likes.

Where do current levels stand? Since September, banking reserves held at the central bank have grown by about $260 billion to $1.66 trillion as of Dec. 25, according to Fed data, which is roughly where Deutsche Bank analysts expect the Fed to target reserve balances for much of 2020.

But Eric Souza, senior portfolio manager at SVB Asset Management, said the Fed should aim even higher, and seek reserves more akin to the cash buffers kept by corporate treasurers.

Public non-financial U.S. companies held a combined $2.3 trillion of cash and equivalent securities as of their most-recent fiscal quarter, up from $1.66 trillion for the full year 2012, according to FactSet data.

BCA’s Swift thinks bank reserves could hit $1.86 trillion by the second quarter of this year, at which time he predicts the Fed’s balance sheet will reach not quite a record $4.49 trillion.

Way forward

The New York Fed has been injecting billions of dollars of liquidity into funding markets and much of these funds take the form of temporary, short-term purchases of assets that are repaid quickly.

As part of these “reverse repo” transactions, broker-dealers often borrow funds overnight (or even for several weeks) from the Fed at its current 1.5% to 1.75% target range, in return for posting collateral such as Treasurys.

To keep market participants funded through the often turbulent Dec. 31 and Jan. 2 period, the Fed announced it would deploy up to $500 billion alone to cushion the market. It ended up funding only $255.6 billion during that window, signaling the Fed injections worked.

“After the enormous support from the Federal Reserve, short-term rates remained well under control over year-end,” wrote John Canavan, a lead analyst at Oxford Economics, adding that fears of a repeat of September’s chaos “turned out to be overwrought.”

Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP, said he expects the Fed’s balance sheet peaked at the end of December, but and will decline as its temporary operations wind down.

Indeed, Fed officials discussed the possibility of gradually moving away from active repo operations in 2020, according to minutes of the Fed’s last rate-setting committee meeting in December, which were published Friday.

But they also said the possibility of a standing repo facility would be debated in future, as well as the merits of setting administered rates, along with the longer-run composition of the Fed’s Treasury holdings.

“It is still a long way to go until the end of the day, but it seems fair to say that the Fed has accomplished its mission in mitigating the risk of a repeat of the repo market volatility of mid-September,” said Thomas Simons, senior money market economist at Jefferies.