The Federal Reserve is expected this week to embark on its first benchmark rate cut since the financial crisis, drawing questions about whether this will mark the first of many, or an ‘insurance cut’ to help extend the U.S.’s recordlong expansion.

The U.S. central bank is expected to lower rates by at least 25 basis points to a range between 2.00% and 2.25% at its July 30-31 meeting.

See: Five things to watch from this week’s crucial Fed meeting

Yet critics underscore it would be a relatively unprecedented occasion to ease policy, with the U.S. labor market at its tightest levels in decades and economic growth still hovering near its long-term trend rate of 2%. Cutting rates in a backdrop of economic strength, critics say, will only serve to fan financial excesses, leading to further pain in the next downturn.

Here’s what investors need to know heading into the week:

Insurance cuts

Weakening global growth, along with a sharp slowdown in business investment, have pushed the U.S. central bank to contemplate a rate cut even when the economy shows few signs of verging on a recession.

Though household spending has held up, analysts say the continued lack of capital expenditures even after President Donald Trump’s tax cuts in late 2017 would weigh on the long-term prospects of the economy. In addition, purchasing manager surveys across the world show factory activity has either stagnated or contracted altogether, even as the services sector has remained resilient.

“Things are slowing a bit, a rate cut is the right thing to do,” said Robert Tipp, chief investment strategist for PGIM Fixed Income, in an interview with MarketWatch.

He pointed out insurance cuts in 1995 and 1998 “worked out great,” lengthening the U.S. expansion.

One of the few examples of a so-called “insurance cut,” the Fed’s easing in the mid-nineties took place in the midst of a U.S. productivity boom and, like today, when the economy was nowhere near a recession. The 1998 cuts were more in response to growing market panic from sovereign debt crises in Russia and Mexico, along with the collapse of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management.

In addition, growing academic research has pointed to the case for preemptive action. Senior Fed officials, including New York Fed President John Williams and Vice Chairman Richard Clarida, have underlined academic research that says once interest rates are near zero, a central bank should move early and decisively.

It is why some say the Fed may be inclined to cut rates aggressively and push for 50 basis points of monetary easing this year. Expectations for a half-point cut stood at around 20%, based on CME Group data.

Read: Rate cut with stock market at all-time highs? It has been done before—but here’s what’s different

But recent data has continued to undercut the Fed’s case for easing policy this month. Second-quarter gross domestic product grew at 2.1%, while the most recent employment report last month showed the U.S. labor market continued to see healthy job gains.

“Many investors I talk to still don’t understand why the Fed wants to cut rates. It is not only U.S.-based investors but also investors abroad asking that question, and many are puzzled why the Fed has suddenly abandoned ‘data dependent,’” wrote Torsten Sløk, chief economist for Deutsche Bank, on Monday.

Stocks are also trading near records, an unusual backdrop for the central bank to ease policy.

The S&P 500 SPX, -0.26% and Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, -0.24% hit all-time closing highs last Friday.

Gearing up

So what should investors expect?

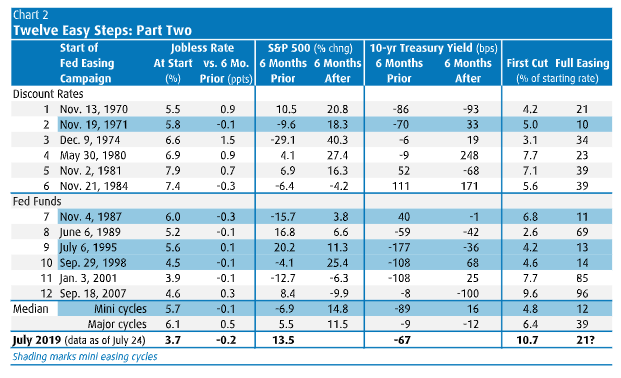

Depending on how analysts consider what counts as a preemptive “insurance cut” and what represents a full-blown easing cycle, investors can reach varying answers. Part of the issue is that the relative infrequency of recessions and easing cycles make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions on how financial markets react in the wake of a cut.

“There is no foolproof, fixed playbook for Fed easing cycles, as every episode has its own quirks and special features,” wrote Douglas Porter, chief economist for BMO Financial Group.

For the Treasurys-market, yields TMUBMUSD10Y, -0.72% showed less direction in the run-up to the expected cut.

Still, Porter says at least one group should be hopeful — stock-markets have tended to climb after past Fed rate-cuts.

“The single biggest takeaway from past easing cycles is that equities have tended to rise six months after the rate cuts began, while bond yields have been nearly flat on average—both in mini and in major easing cycles,” said Porter.

He pointed out the double-digit gains posed by the S&P 500 in the six months after a cut in the last seven out of 12 easing cycles since 1970.

BMO Capital Markets

BMO Capital Markets

But others said it depends whether you think any coming rate cut will be the first of many, or a single cut that successfully arrested a U.S. slowdown.

“What’s interesting is if it is just an insurance cut, and it is one and done, the markets tend to mean revert quite quickly, usually in after one to two months,” Erin Browne, a portfolio manager at Pimco, told MarketWatch in an interview.

In her analysis, stocks tended to climb briefly and the U.S. dollar would fall around one to two percent, but the post-easing impact would fade. However, if the Fed was expected to follow up with further rate-cuts, the impact on financial markets could prove more lasting.

“When you have a more sustained rate cut path articulated by the Fed, that is when you see a more sustained move, either the dollar continues to depreciate, or equities continue to rally. A lot of it is going to depend on future rate cuts and the path dependency of Fed policy,” said Browne.

Check out: Greenspan says it is sensible for the Fed to think about ‘insurance’ cut

Financial instability

Some investors worry lowering rates during a time of economic resilience may end up contributing to financial instability, encouraging companies to lever up their balance sheets and investors to buy up riskier corporate debt.

With corporate debt levels relative to the U.S. economy near records as a result of ultralow interest rates, analysts worry any premature easing could exacerbate the U.S.’s mounting debt problems.

Total corporate debt to gross domestic product stands at 74%, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

“In the short-term, a rate cut will help fuel demand for corporate bonds. We’re already seeing that this year, because there is no alternative,” said Jody Lurie, corporate credit analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott, in an interview with MarketWatch.

But she said it remains an open question whether a rate cut would lead investors to dive for lower-rated corporate bonds as it depended on how the yield curve reacts to the Fed’s first cut in a decade. Most expect looser policy to push short-term yields lower, widening the gap between longer-term yields and steepening the curve.

However, if inflation pressures stay muted even if the Fed eases policy, long-end yields may not have much room to rise, preventing the yield curve from steepening as much as expected.

A steeper curve would imply a more solid growth backdrop, and a safer environment to take on credit risk, she said.

Also check out: Two ‘insurance’ rate cuts from Fed in ’90s produced no big shocks to corporate bonds, Goldman Sachs says