Investors don’t think the Federal Reserve is being straight with them, according to a survey published Wednesday by RBC Capital Markets.

In October, the Federal Reserve announced it would expand its balance sheet by purchasing U.S. government debt from major banks, in exchange for newly created bank reserves, but has been eager to tell markets that this action is not a resumption of quantitative easing (QE) — its post-crisis program of purchases of long-term government debt and mortgage bonds meant to stimulate economic growth and avoid deflation.

”I want to emphasize that growth of our balance sheet should in no way be confused with the large-scale asset purchase program that we deployed after the financial crisis,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said in October.

Powell said that because the balance sheet expansion will only involve the purchase of short-term securities, and is aimed at managing the level of bank reserves in the financial system rather than pushing down long-term interest rates, the actions should be seen as a simple extension of the Fed’s day-to-day market operations.

But investors are not heeding this advice, according to RBC’s December survey of institutional investors, with 52% of those surveyed saying that the Fed’s action is “effectively a form of QE,” while only 19% agreed with Powell’s description of the program and 23% said they don’t know.

“We are inclined to agree with the 19% that say it isn’t [QE] and have a lot of sympathy for those that say they don’t know,” wrote Lori Calvasani, head of U.S. equity strategy at RBC in a note accompanying the survey.

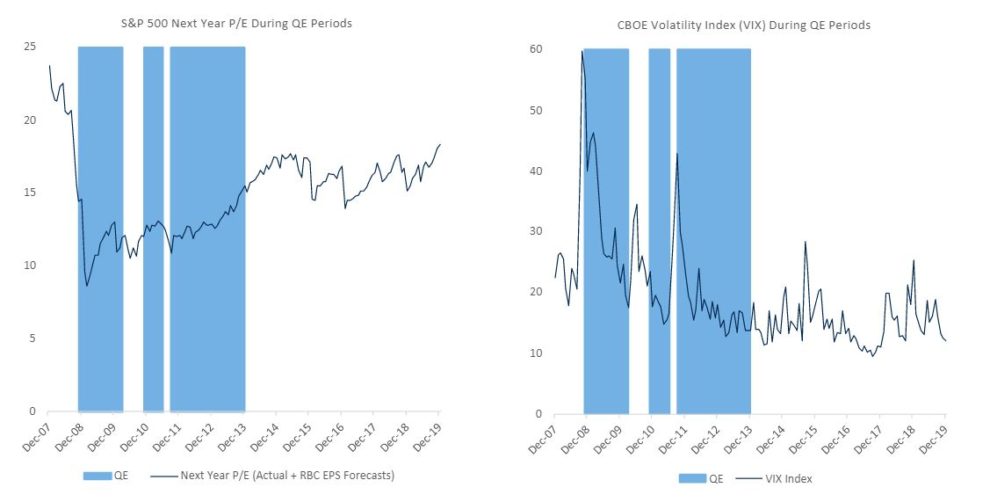

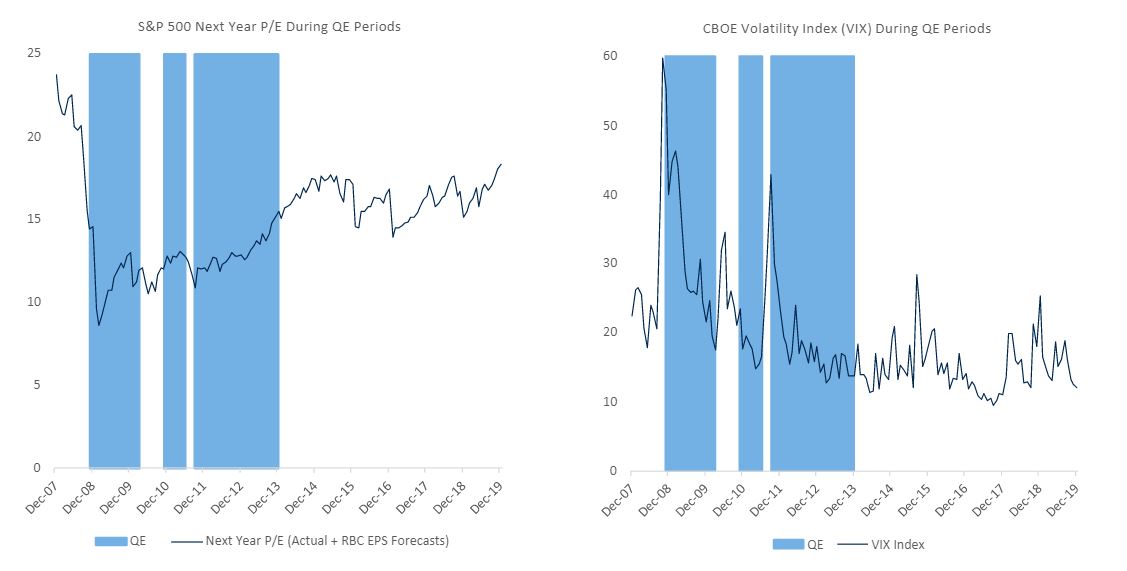

However, if the majority of respondents are correct, then she argued that her 3,350 target for the S&P 500 index for 2020 year-end would be too conservative, because “QE is something we think could cause price-to-earnings multiples to expand” whereas her baseline view is that there will be no broad valuation expansion in the coming year.

“During historical periods of quantitative easing, the S&P 500’s [earnings multiple] expanded substantially while the programs were in place,” she wrote. “At the same time, the VIX VIX, -0.32% also came down from elevated levels.”

The Cboe Volatility Index, or VIX, uses S&P 500 options trading to reflect the market’s expectation for volatility in the coming 30 days.

This raises the question, however, of why quantitative easing tends to lead to higher equity prices.

Stephan Luck and Thomas Zimmerman of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York present evidence that purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in particular boosted bank lending, boosting economic growth and therefore stock prices. Since the Fed is not increasing its purchases of MBS during the current balance sheet expansion, investors should not expect higher stock prices to result.

But other economists have argued that QE works because its a signalling mechanism to markets that it will keep short term interest rates low for a very long time. “Economic theory tells us that long-term rates are mainly determined by what investors expect short-term rates to be in the future,” wrote Edison Yu, economist and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, in a review of the economic literature on the bond-buying program.

“QE may affect expectations about future rates,” he continued. “QE might make the Fed’s promise to hold rates low for a long time more credible, making QE a signaling mechanism.”

If this signaling channel is in fact a major mechanism by which quantitative easing lowers interest rates and boost stock prices, it may not matter what the Fed calls it, if investors believe it is QE.

div > iframe { width: 100% !important; min-width: 300px; max-width: 800px; } ]]>