Unreported loans from Chinese state banks to governments in emerging markets is causing nervous Wall Street investors to sit up and pay attention.

A wide swath of these loans slips under the radar as China doesn’t need to disclose the terms and size of their overseas loans to international organizations, a particularly troublesome issue for emerging market bond buyers who worry they may be flying blind, according to Erin Browne, a portfolio manager at Pimco.

Without complete information on a country’s commitments, bondholders are unsure how they rank against Chinese creditors when the debt runs into trouble, or even defaults, Browne said a recent interview with MarketWatch. That can make it difficult for investors to figure out how much of their investment’s value might be written down as part of a broader debt restructuring.

“Lending by sovereigns that are not part of the official institutional sector is the biggest risk for emerging markets right now – it clouds the waters with respect to how official sector involvement will be during times of distress,” Browne said.

“That debt is not transparent to the IMF and to other borrowers that have issued to these countries. If they were to default, or if they were to go in a period of distress, it would be contingent on China setting the rules in terms of working out that debt,” she added.

A new paper by Sebastian Horn and Christoph Trebesch of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy and Carmen Reinhart of Harvard University estimates that around an outstanding $200 billion of Chinese overseas loans remain reported as of 2016.

The lack of transparency has drawn attention from international development organizations. World Bank President David Malpass called on China to open up its overseas lending books in his first public appearance in his new role.

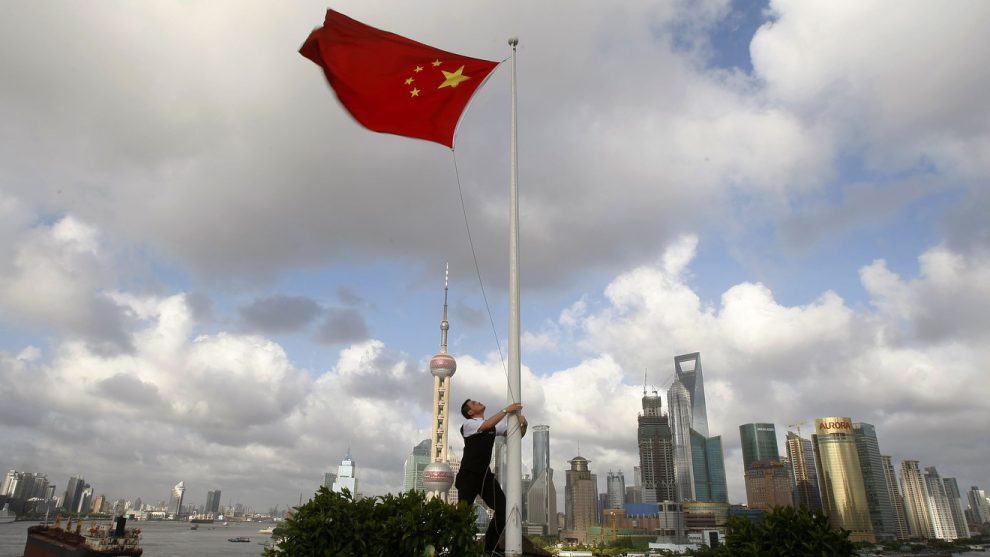

The rise in Chinese overseas loans has followed Beijing’s growing engagement with the world as it seeks to secure oil and other natural resources to fuel its rapid economic development. More recently, the One Belt One Road initiative has funneled hundreds of billions of dollars for the construction of roads and bridges throughout Asia, Europe and the Middle East.

Much of this Chinese lending has been carried out through two government-associated policy banks, China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank, both of which have carried out three-quarters of Chinese overseas lending.

These state-owned banks aren’t obligated to report their activities to international financial organizations such as the Bank of International Settlements and the International Monetary Fund.

In addition, China is not a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nor the Paris Club, a group of institutions that coordinate debt relief solutions for troubled government borrowers, so even loans made directly by the Chinese government do not need to be publicly disclosed.

Though many concede the lack of transparency can prove a problem, claims that Chinese lending to emerging markets constitutes a form of “debt-trap diplomacy,” or the use of uneconomic loans to secure strategic ports or to buy influence with governments, are more widely contested.

“There’s very few signs China is lending into projects for politics and strategy,” said Hayden Briscoe, head of fixed-income at APAC for UBS Asset Management, who has bought bonds issued by China Development Bank.

Muddy Waters

The murkiness around Chinese overseas lending is compounded by Chinese policy banks who lend to so-called quasi-sovereign state-owned enterprises such as the oil companies PDVSA of Venezuela and Petrobras of Brazil.

Debts of these state-backed firms often don’t have to be revealed on government balance sheets, even though the implicit government imprimatur means during times of trouble it can result in broader contagion and weigh on the state’s overall creditworthiness.

Moody’s Ratings in a March report said the lack of transparency into off-the-book loans was difficult to anticipate and could weigh on a country’s credit rating.

Investors tended to demand an extra yield premium when lending to countries that don’t offer full transparency into how they spend and borrow money, said Vivek Ramkumar, senior director of policy at the International Budget Partnership.

A classic example of unreported lending going awry was the Mozambique’s “tuna bond” scandal in 2016, when Credit Suisse and Russia’s VTB bank helped investors buy $900 million of bonds dedicated to procuring a tuna fishing fleet. Unbeknownst to these money managers, the banks had also made $622 million of undisclosed loans for navy boats.

Only when Mozambique started the process of renegotiating its delinquent debts, did investors find out the country was in a more precarious financial situation than they had thought, reducing the amount of money they could recoup from their bad investments.

To be sure, worries that unreported lending may result in emerging market investors flying blind isn’t a new issue.

It was a widespread problem in the 1970s and 1980s when governments had directly lent to African countries in return for shipments of natural resources, but some didn’t realize that other countries had also made similar competing loans to the same borrower.

This meant when commodity prices slumped, these African nations had more debt than they could contend with, said Gregory Smith, fixed-income strategist for Renaissance Capital and a former economist at the World Bank.

“Typically these loans aren’t discovered until there’s a problem. You often had countries saying I didn’t know you were lending, otherwise I wouldn’t have done it,” said Smith.

This lack of transparency isn’t only an issue for creditors but also for governments of emerging markets which may not have a full understanding of their own finances.

In one of the few debt restructurings that have involved Chinese creditors, the IMF approved a bailout to the Republic of Congo after China agreed to restructure a chunk of its loans in April.

But negotiations briefly stalled after the IMF demanded the Republic of Congo figure out how much of it was owed to China in order to qualify for a bailout. Without the figures immediately at hand, Prime Minister Clement Mouamba flew to Beijing last year to get a full account of how much funds Chinese banks had extended to Congo, sometimes via its opaque national oil firm Societe National des Petroles du Congo.

“It is possible that officials in countries with poor governance and poor financial management systems won’t fully know lending by the country as a whole,” said Ramkumar.

Few Examples

Investors say there’s few examples of debt restructurings and defaults involving Chinese creditors to learn from, so it’s difficult to forecast how Western investors will ultimately fare when a government struggles to pay its obligations.

“We haven’t had many debt workouts involving China,” said Smith.

It’s why many are looking to Venezuela as an important case study. The country officially defaulted on its obligations in 2017, leading to heated speculation on how the restructuring of its hefty debt pile might shape up.

Investors anticipate the expected debt workout for the oil-rich nation to be complicated by its diverse set of creditors, including hedge funds, emerging market debt managers, not to mention China and Russia.

Chinese financial institutions are estimated to have around $20 billion of loans to Venezuela still outstanding, according to figures provided by China’s Commerce Ministry as reported by the Wall Street Journal.

The Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington-based think tank, estimates that Chinese policy banks have lent around $67 billion to Venezuela since 2005.

A group of holders of Venezuelan bonds said if the debt is eventually restructured, loans from China and Russia should not should be excessively elevated over their own claims, and so-called haircuts, or write-downs of the debt’s face value, should be applied equally across the board.

Briscoe said Venezuela’s bondholders are rightly concerned about the seniority of their commitments.

He said most of the Chinese loans by its state banks were backed by shipments of physical commodities like oil. With most of the collateral in Venezuela tied to the country’s endowment of natural resources, Western bondholders may recover less money during a restructuring than they had anticipated, as Chinese lenders have a strong claim on the revenues from the sale of these commodities.

“You’re definitely subordinated to lenders who have collateral over those oil revenues,” said Briscoe.