U.S. stock benchmarks enjoyed a nearly unfettered run-up toward records on the week — with the rally pausing briefly Friday — on the back of the Federal Reserve’s easier monetary-policy stance.

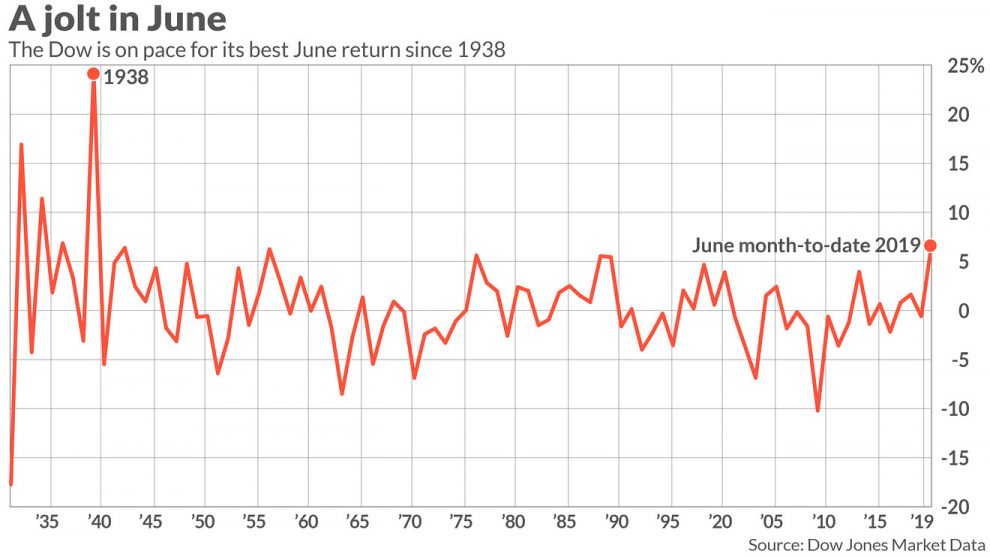

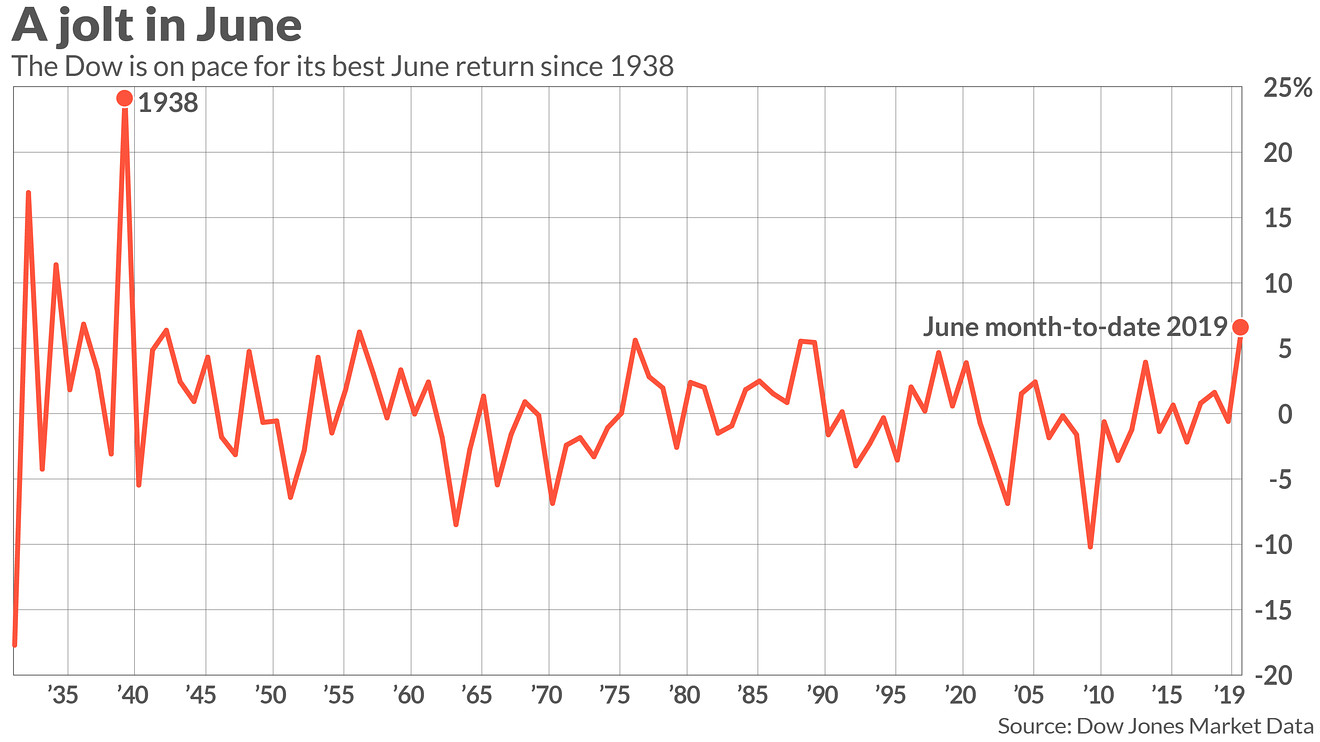

Recent gains have put the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -0.13% in position to ring up its best June gain of 7.7% since 1938 when the blue-chip benchmark surged an eye-popping 24.3% on the month, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

The S&P 500 index SPX, -0.13% is on track for its best June return, with a gain of about 7.2%, since 1955 when the broad-market benchmark rose 8.2%, while the Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, -0.24% was on track for a 7.8% return in June, which would represent its best June since a 16.6% gain back in 2000. The S&P 500 notched its first record close since April 30 on Friday, while the Dow is off less than 1% short of its Oct. 3 all-time closing peak.

The rally for equities has been partly supported by the Fed, which concluded its Wednesday rate-setting meeting by signaling a willingness too trim rates as soon as the end of the July 30-31 gathering to curb the effects of tariff clashes between the U.S. and international trade partners, notably China, that have roiled global economies and threaten to disrupt global supply chains.

Wall Street has been pricing in as many as three rate reductions in 2019, according to CME Group data, tracking federal-funds futures.

Stocks can rise in an environment of falling benchmark interest rates because it translates to comparatively cheaper borrowing costs for individuals and corporations. Still, a rate cut could also signal a more bearish turn in central bankers’ reading of the economic environment which could eventually hurt investor sentiment.

Gains for stocks also come as bond yields across the globe have been mostly rallying, driving their yields which move in the opposite direction, solidly lower. Bond prices don’t usually rise while stocks are climbing because bonds are perceived as assets investors flee to during times of uncertainty while equities rise when appetite for risky assets rises.

The yield for the 10-year Treasury note TMUBMUSD10Y, +1.65% sank under 2% earlier in the week, while the comparable German bond TMBMKDE-10Y, +10.99% known as bunds, also briefly touched a record-low yield of negative 0.322%.

Back in 1938, the U.S. economy faced a slump as a recovery from the Great Depression stalled, until Franklin D. Roosevelt in his second term got a $3.75 billion spending program approved by Congress in the spring of that year to help stimulate sluggish expansion, increasing deficit spending.

The move, at least in part, helped to jolt blue chips as fiscal stimulus measures were used to combat unemployment which hit 19% in June of 1938 as manufacturing activity weakened.

This time around, however, U.S. unemployment stands at 3.6% even if the May report, with 75,000 jobs created, fell far short of expectations for a gain of 185,000 on the month.

—Ken Jimenez contributed to this article