Wall Street is still weighing the implications of the Federal Reserve’s most substantive shift in the way it thinks about monetary policy in years.

In essence, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell on Thursday emphasized the primacy of the labor market in its mandate, even if it means that inflation rises above an annual 2% target that the central bank has traditionally deemed as indicative of a healthy, well-functioning economy.

Powell’s new policy framework comes after 18 months of review by the interest rate setting Federal Open Market Committee and marks a subtle tweak from targeting 2% inflation to now allowing for undershoots and overshoots that would see inflation average 2% over time.

“This change may appear subtle, but it reflects our view that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation,” Powell said in his webcast speech as a part of the annual Jackson Hole symposium on Thursday.

Indeed, the shift is a big deal experts say, and not just because of the defenestration of decades of central-bank orthodoxy centered on the relationship between the labor market and price pressures, but because it expresses policy that may be far removed from a policy such as advocated by Stanford University economist John Taylor, who has championed a mathematical approach to setting interest rates.

The Fed’s new approach, instead, may raise more questions than answers about implementation and crucially how it achieves inflation targets that have thus far remained elusive over the past decade.

“How much inflation is the Fed comfortable with?” asked Aneta Markowska, chief economist at Jefferies in a Friday research note.

“The FOMC was surprisingly vague with respect to its inflation averaging framework, saying merely that it will aim to achieve inflation ‘moderately above 2 percent for some time’ following periods of undershoots. What does that mean in practical terms? We simply don’t know,” the economist wrote.

After Powell’s Jackson Hole speech, some Fed officials did attempt to provide some sense of the degree to which inflation might be allowed to rise above the central bank’s target before raising alarms.

“To me, it’s not so much the number, whether it’s 2.5% or 3%,” Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker, a voting member of the FOMC, told CNBC in a Friday interview. “It’s whether it’s reaching 2%, creeping up to 2.5% or shooting past 2.5%,” he said.

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, who is not currently a voting FOMC member, said on Friday that inflation could remain at around 2.5% “for quite a while.”

Inflation plays a key role in Fed policy because too-low inflation can lead to a weaker overall economy, as it can encourage consumers, the main driver of the U.S. economy, to delay purchases, as well as amplify expectations for even lower prices, fostering a potentially vicious cycle. As the Fed has put it, “if inflation expectations fall, interest rates would decline too.”

And receding interest rates make it difficult for the Fed to use its main tool for managing monetary policy: the federal funds rate. The Fed lowers its benchmark interest rate to stimulate economic activity and raises it to slow it.

It is worth noting that he Fed has raised interest rates nine times between 2015 and 2018.

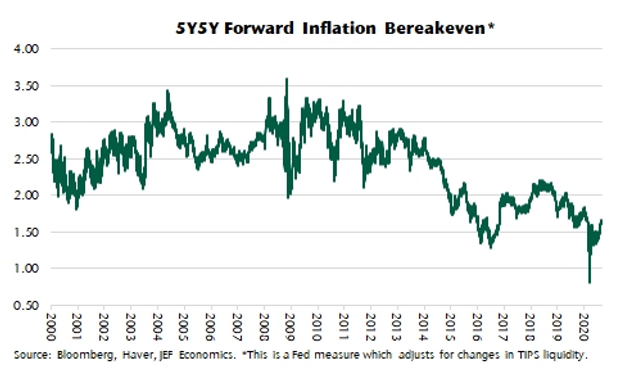

However, from at least 2009 prices pressures have been nowhere seen, based on 5-year, 5-year forward inflation break evens, which are at 1.6%. That measure of inflation calculates the expected pace of price increases over the five-year period that begins five years from now.

A lack of clarity on the specifics around its altered policy could inject more uncertainty into the market over the longer term, experts said.

“When it comes to the shift in how the Committee views its inflation objective, much was left unsaid, and careful consideration suggests that the new approach may actually complicate the policy process in terms of both implementation and communication,” Robert Eisenbeis, chief monetary economist at Cumberland Advisors, in a Friday note.

Eisenbeis says that the Fed didn’t immediately specify which inflation measure it would use. Traditionally, the central bank’s preferred inflation gauge, is the PCE price index, or personal-consumption expenditures price index, but the commonly referenced gauge on Wall Street is the CPI, or consumer-price index.

“Finally, the elephant in the room is the fact that the [Fed] has pursued a 2% inflation target since January 25, 2012, but has continually undershot that level,” The Cumberland analysts wrote.

What’s the outlook?

“The Fed will now need to really explore this new regime change in the FOMC meetings, as it is great telling us they plan but how they enact is what the market really needs to learn,” wrote Chris Weston, research analyst at broker Pepperstone.

Lara Rhame, chief U.S. economist at FS Investments, says that the implications of the Fed’s moves may not play out until after this COVID-19 crisis is over.

” The real issue for investors will be what comes after this economic crisis,” the economist wrote.

“Many hope that over the coming year or two, the economy will continue its recovery. This could happen even faster should a vaccine or more effective treatments help suppress the pandemic,” the FS Investments analysts said.

“But [Thursday’s] announcement has made clear that even a return of steady, potential growth would mean the Fed would likely leave rates where they are—at zero,” the economist said.

The Fed’s coming Sept. 15-16 policy meeting may fill in some of the blanks for market participants.

Implications for markets

So what does this all mean for financial markets ?

It implies a regime of potentially lower interest rates but market expectations for volatility may increase, without more guidance on how the Fed’s policy will play out.

In the short term, stocks could continue to rise or at least be inclined to hold steady with the Fed more explicitly indicating no intention to raise interest rates soon.

“One of the few things that could have knocked the market down was the Fed could start to raise rates…I don’t know if this [policy shift] is going to lead to a further meltup, but I certainly thing it does put a more secure foundation under the market,” Brad McMillan, chief investment officer at Commonwealth Financial Network, told MarketWatch.

On Friday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.56% closed about 3% from its Feb. 12 record closing high, while the S&P 500 SPX, +0.67% and the Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, +0.60% both finished at records.

“It’s hard to bet against the equity market right now,” said David Donabedian, chief investment officer of CIBC Private Wealth Management, in emailed comments.

Commonwealth’s McMillan also said that the growth stocks, which have notably been on a tear, are likely to continue to benefit in the short-term low-interest rate regime. “Future cash flows will be worth more in the present for those companies which can generate it,” he noted.

“Those companies with pricing power, such as commodity stocks, will benefit. Banks will finally enjoy a steepening yield curve. For those without pricing power and thus have to eat rising cost pressures, profit margins will get squeezed and that won’t be a good thing,” wrote Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer, at Bleakley Advisory Group, in a Friday note.

“Cheap stocks, the so called value side, have already inherently built in low expectations so they would be more immune. Interesting times,” he said.

Analysts at BofA Global Research, including Michelle Meyer, said they don’t expect a broad run-up in the U.S. dollar DXY, -0.75% after Powell’s statement.

The analysts wrote in a Thursday report that “a broad USD rally may ultimately be contained absent another bout of risk aversion, as USD shorts have been concentrated in the typically less price-sensitive asset manager community.”

In theory, a longer-run of lower interest rates and higher inflation should provide support for gold and silver prices, which have already drawn considerable safe-haven flows as investors have fretted about the economic implications of the coronavirus on business activity world-wide.

Gold GOLD, +2.45% and silver SI00, -0.01% to a lesser extent are viewed as hedges against uncertainty and rising inflation. Weakness in the U.S. dollar, or at least a stable greenback, could also help buttress prices for precious metals.

Add Comment