The stock market is generally expected to benefit from inflation, but a long-predicted surge in U.S. prices rattled investors in the past week. A closer look at the historical record might indicate the source of concern, according to one Wall Street analyst.

For equities, there is “good” inflation and “bad” inflation, said Nicholas Colas, co-founder of DataTrek Research, in a Thursday note. Good inflation lifts corporate earnings as long as employment remains high; bad inflation causes recessions, undercutting corporate earnings.

“Markets are volatile because they’re not sure which sort of inflation we have at present, or what (if anything) the Federal Reserve may do to bring inflation down,” he wrote.

Stocks fell sharply on Wednesday after data showed the U.S. consumer-price index, or CPI, rose by a hotter-than-expected 4.2% year-over-year in April. Equities bounced Thursday and Friday, but suffered weekly losses, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +1.06% down 1.1% and the S&P 500 SPX, +1.49% retreating 1.5% after closing at records on May 7. The Nasdaq Composite COMP, +2.32% fell 2.3% for the week.

It may be that stocks were merely due for a pullback after a long run to the upside to new records for the benchmark indexes and some analysts feared stocks had largely priced in much of the good news around the expected post-pandemic recovery.

Indeed, Colas questioned whether a single month’s reading was responsible. He noted that the 10-year Treasury yield TMUBMUSD10Y, 1.625%, which would be expected to rise if investors feared the Federal Reserve was behind the curve, saw only a modest bump and remains well below its March high above 1.75%.

Those that blamed the pullback in stocks this week on the inflation data fell into two camps. Depending on an investor’s point of view, the inflation reading either raised fears that the Fed would move more quickly than it has signaled to rein in monetary stimulus, or that it was making a policy mistake by insisting on maintaining easier policy in the face of building price pressures.

See: The biggest ‘inflation scare’ in 40 years is coming — what stock-market investors need to know

For their part, Fed officials this past week reiterated their expectation that inflation will surge in coming months thanks to pent-up demand for goods and services and supply bottlenecks, but will fade over the longer term. Powell and other policy makers have said it’s too early to begin thinking about withdrawing monetary support until the labor market is more fully recovered from the pandemic.

Market bulls, meanwhile, contend that even if the Fed is risking a bout of runaway inflation, the stock market should benefit.

Jeremy Siegel, finance professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, has warned that the economy could see inflation rise by a cumulative 20% over the next two to three years. But, he argued in a CNBC interview Friday, the fact that stocks are “real assets” — backed by capital, intellectual property rights, trademarks and other holdings — explains why they’ve historically served as an inflation hedge.

Moreover, the prospect of negative real returns makes cash and bonds an unappealing alternative, he said, while relatively strong stock-market dividends were likely to keep money flowing into stocks until the Fed finally begins to rein in monetary support.

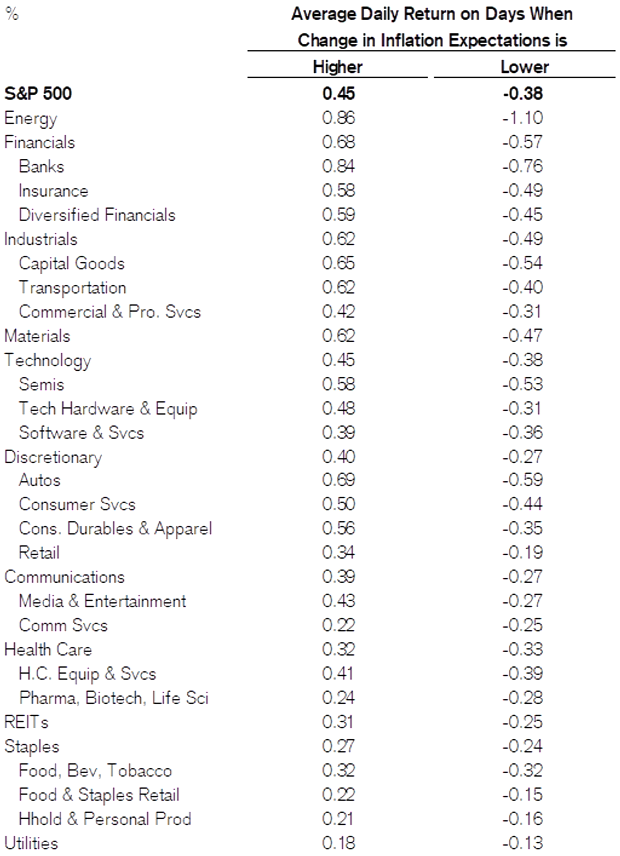

Jonathan Golub, chief equity strategist and head of quantitative research at Credit Suisse, reiterated the positive correlation between stocks and inflation expectations in a Thursday note. While the correlation is positive across styles and sectors, those that tend to benefit from rising interest rates and are more sensitive to the economic cycle tend to do best when inflation expectations are on the rise (see table below):

But what does history say about stock prices and long stretches of high inflation?

Colas took a look back at periods of high inflation, which he defined as the consumer price index running above an annual clip of 5%. He found only two such periods of protracted inflation since 1928.

The first ran from 1941 to 1951, encompassing World War II and the start of the Korean War. The second bout ran from 1969 to 1982, from the Vietnam War through the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979. Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 saw the CPI jump to 5.4%, he noted, but it was a one-time spike.

And how did stocks perform?

Colas found that from 1941 to 1951, the S&P 500 index appreciated by 310% on a nominal basis and saw a 121.1% rise on a real, or inflation-adjusted, basis. The 1969-to-1982 stretch saw a 176% nominal appreciations. But it saw a negative 11.6% real return.

It goes to show that context matters when it comes to inflation, Colas said.

The S&P 500 did well during and after World War II with a compounded annual growth rate of 7.5%, after being on the winning side of a global conflict, he noted. But it struggled to keep up with inflation in the 1969 – 1982 period, posting a compounded annual growth rate of negative 0.8%, as the economy and the labor market were rocked by rising energy prices.

The lesson, Colas said, is that inflation “is just one input into equity prices and returns, and on its own explains very little about how stocks will do over the longer term.”

The uncertainty around what sort of inflation may be in store is enough to spark increased volatility, he said, but isn’t sufficient to conclude that equities will underperform in coming years.