It might take a market mishap to end a debt-ceiling standoff that threatens to trigger a previously unthinkable default on U.S. government debt.

“An interesting question now is whether financial market vigilantes, in bonds, stocks or even currencies could flex their muscles the closer the government gets to running out of cash,” said Steven Barrow, head of G-10 strategy at Standard Bank, in a note late last week.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on Monday warned that the U.S. government could exhaust its ability to pay its bills as early as June 1 if the debt-ceiling isn’t lifted. The government technically bumped against the $31.4 trillion limit on borrowing earlier this year, but has employed accounting maneuvers that have allowed it to continue meeting payment obligations to bondholders and others.

See: Why the debt-ceiling showdown is a ‘Catch-22’ for markets after House passes bill

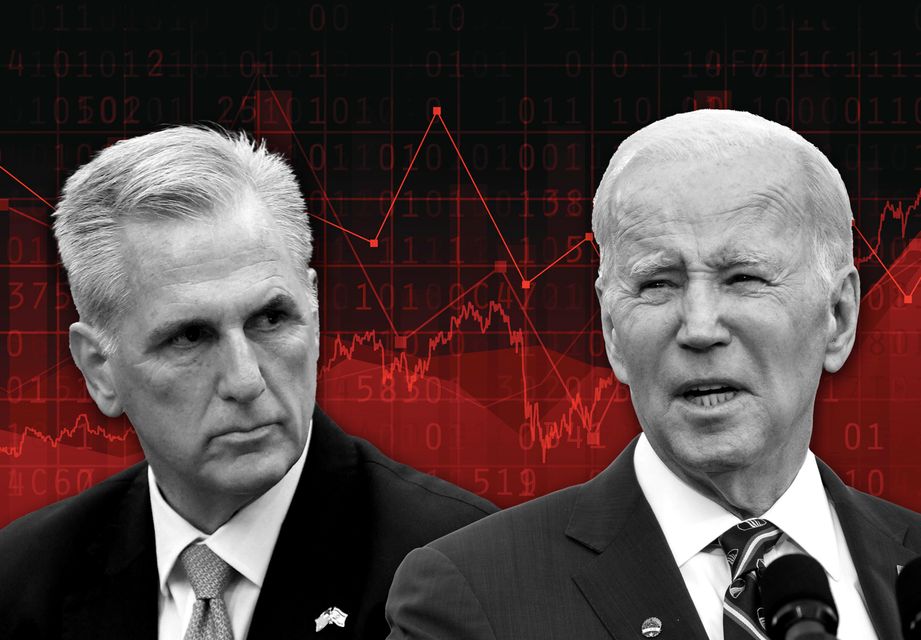

Late Monday, President Joe Biden invited House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-California, and other congressional leaders to a meeting May 9 at the White House.

McCarthy and congressional Republicans want spending cuts in exchange for raising the borrowing limit, while the Biden administration insists it mut be raised without condition. The Republican-controlled House last week narrowly approved a bill that would raise the debt limit, but the legislation is seen as a nonstarter in the Democratic-controlled Senate.

Read: Debt-ceiling standoff: Here’s what’s next, as U.S. faces potential default on June 1

Disappointing tax receipts in April have brought forward the so-called X-date when the Treasury would run out of special maneuvers that would allow it to continue making all its payments. Analysts fear an early June deadline may prove impossible to meet.

“There’s no chance — none — that the House-passed budget deal could win enactment in the Senate, where leading Republicans are reluctant to get involved,” said Greg Valliere, chief U.S. policy strategist at AGF Investments, in a Tuesday note. “In the House, a couple dozen hard-liners have no interest in raising the debt ceiling if the Senate modifies their bill.”

So what would it take?

“That’s easy — a stock market meltdown or signs of a looming recession. Without a catalyst, Congress will continue to dither and posture. Are the markets worried about a default? Apparently not yet, but that could change by Memorial Day,” Valliere said.

The stock market has largely brushed off the issue, so far. Major indexes saw gains in April. The S&P 500 SPX, -1.58% is up nearly 9% for the year to date, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, -1.53% has gained over 2% and the Nasdaq Composite COMP, -1.35% has rallied nearly 17%.

U.S. stocks fell sharply Tuesday morning, with the Dow sliding over 500 points, or 1.6%, while the S&P 500 dropped 1.7% as regional bank stocks suffered another round of steep losses.

The debt-ceiling impasse has roiled corners of the market for government debt, sparking volatility in the market for short-term Treasury bills as investors shun debt that could be affected by a potential default. The cost of insuring U.S. government debt against non-payment using financial instruments known as credit-default swaps has soared to more-than-a-decade high.

Would stock-market chaos get the job done?

There’s precedent. The Dow plunged over 700 points in a single session in late September 2008, a move that was then the largest point drop on record and marked a fall of more than 7%, after the House rejected legislation to establish the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, following the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Analysts argue that the market panic helped consolidate support for the controversial legislation, which was subsequently passed and signed into law by President George W. Bush in early October. (To be sure, not everyone agrees that the market slide did the trick.)

The question now is whether market participants will blink as the standoff goes down to the wire, Barrow wrote.

He expects to see some buildup of pressure in the form of weaker stocks, higher yields for short-term assets that would potentially be unpaid, and a weaker U.S. dollar, but warned that the moves wouldn’t be on par with what would occur in the event of a technical default — or even a scenario in which technical default is averted but credit ratings firms take the U.S. down another notch as they did in 2011.

Policy makers, meanwhile, should take a lesson from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March, which came after customers pulled deposits at an unprecedented pace, demonstrating the interconnectedness of the financial system in the digital age.

“This surely must be a warning that, when it comes to the debt ceiling, if there is some sort of run on the U.S. either before, or after the X-day, it could be much faster and probably much deeper than we’ve seen before,” Barrow wrote. “In short, the stakes seem much higher and investors will just have to hope that the politicians appreciate this.”