Lucy Hewett

Lucy Hewett

This is the second in MarketWatch’s series about programs that offer high-school students the opportunity to take college classes. The series was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program. (Read parts one, three, four, five and six.)

“That was wild.”

That’s how Victor Orduna describes his life as a teenager in southwest Chicago’s Gage Park neighborhood. And he isn’t talking about partying with friends or other high-school high-jinks.

Orduna is referring to his schedule. The now 19-year old would wake up around 6:30 a.m., head to his high school until the late afternoon, and then clock in for his job at a local supermarket, where he’d bag groceries until 10:30 p.m. Some weekends, Orduna worked the late shift at a pizzeria, slinging pizzas and cooking burgers until 1:30 a.m.

In between work and his high-school responsibilities, Orduna found time to take a few courses at the local community college, working with his boss at the grocery store to cut down on a couple of shifts per week.

“When I wasn’t in school I was at work,” he said.

Courtesy of Victor Orduna

Courtesy of Victor Orduna

Orduna was one of more than 4,000 students who graduated from Chicago Public Schools in 2018 with credit earned through college courses taken in high school, a program known as dual-credit or dual-enrollment.

Black and Hispanic high-school students are also less likely than their white or Asian counterparts to have taken a college course in high school.

So far, it appears the hustling has paid off. Orduna, the son of immigrants and the first person in his family to go to college, recently wrapped up his freshman year at his state’s flagship college, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

He arrived with 18 college credits, sparing him from introductory courses and offering the potential to save time and money towards his engineering degree.

Stories like Orduna’s illustrate how the power of taking college courses in high school can help propel a student’s trajectory. But stories like his are still relatively rare. Even as dual-enrollment opportunities have expanded rapidly, they haven’t necessarily been spread equally. That means often the students who would benefit the most from the programs — low-income students and first-generation college students — never get the chance to participate.

MarketWatch photo illustration

MarketWatch photo illustration

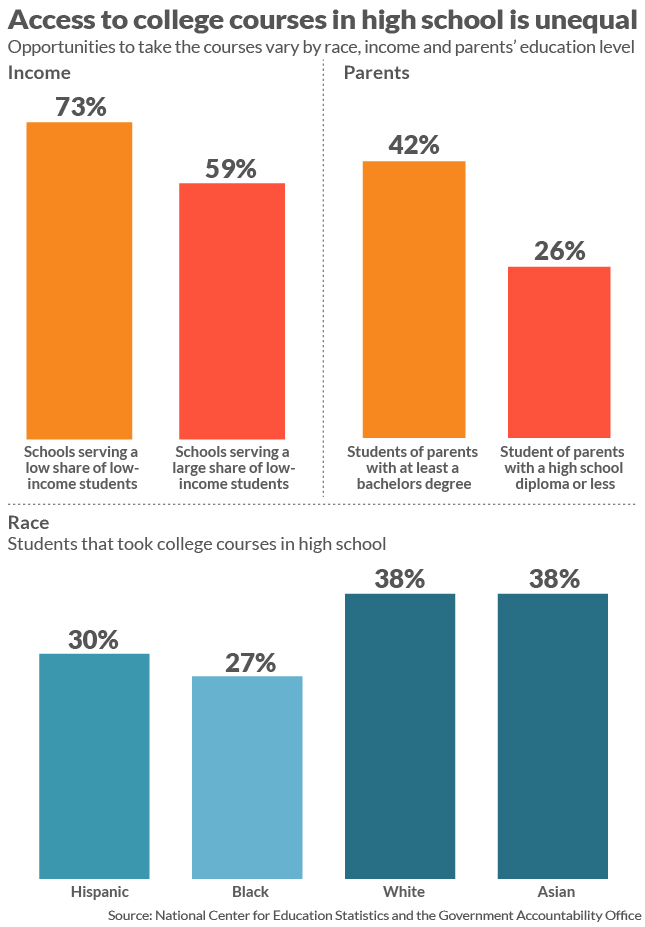

Low-income high-school students are less likely to take college classes

During the 2015-2016 academic year, schools where the bulk of students qualified for free and reduced-priced lunch — a proxy for low-income — were less likely to offer dual-enrollment courses than those where less than 25% of students were eligible for subsidized lunch, according to the Government Accountability Office.

Black and Hispanic high-school students are also less likely than their white or Asian counterparts to have taken a college course in high school, research from the National Council for Education Statistics found.

In addition, students whose parents have a bachelor’s degree are more likely to take a college course in high school than those whose parents didn’t go to college, according to NCES.

“Access to dual enrollment is inequitable,” said Davis Jenkins, a senior research scholar at Columbia University’s Community College Research Center.

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

Terrence Horan/MarketWatch

One reason: The general inequity that affects the K-12 education system. Schools with fewer resources may not have enough money to hire the teachers necessary to offer these programs. (They typically are required to have advanced degrees.) In addition, the schools may not have the funds needed to coordinate the logistics involved in sending high-school students to community colleges for class.

But in some cases, states and localities make choices, including charging fees for the dual-enrollment courses or only enrolling students already pegged for college success. That can widen the gaps in access to a quality education even further, student advocates say.

Black and Hispanic high-school students are also less likely than their white or Asian counterparts to have taken a college course in high school.

As these programs have expanded, ensuring that all students have equal access to them has increasingly become a concern for policy makers, researchers and educators at all levels. There’s even been a national policy response.

Beginning in 2016, the U.S. Department of Education began experimenting with allowing some high-school students to use Pell grants, the money the government provides low-income students to attend college, to pay for dual-enrollment courses.

Ideally, tapping Pell grant dollars would broaden access to these programs for low-income students, but it’s still too early to tell whether that’s happening. The results of that experiment, which has been going on since 2016, aren’t yet available, according to the Department.

Despite these efforts, “like everything else, guess what’s happening here? The haves are getting more and the have-nots are being left behind,” said Barmak Nassirian, Director of Federal Policy at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

Chicago is making efforts to expand dual enrollment and dual credit

In Chicago, pushing high schools to offer students more opportunities to earn college credit has become part of a broader strategy to prepare students for life beyond graduation, officials there said.

Given the demographics of Chicago Public Schools — nearly 77% of students are economically disadvantaged and more than 80% are black or Hispanic — officials have framed the efforts as one way to get more students to college who have historically been under-represented on our nation’s campuses.

At a conference table in her brightly decorated office, Janice Jackson, the chief executive officer of Chicago Public Schools, touted the power of entering college with a few credits to boost students’ confidence.

A lot of students suffer from “imposter syndrome,” where they feel like they’re not supposed to be there or they don’t know if they’re supposed to be there,” said Jackson, a first-generation college student herself. Students who have a couple of college courses under their belt, “just know that they belong and more importantly they know that they’re prepared.”

Jeff Schear/Getty Images for Essence

Jeff Schear/Getty Images for Essence

The experiment doesn’t come without a cost to Chicago and Illinois taxpayers. In 2018, City Colleges of Chicago, the city’s community college system, waived $1.3 million-worth of tuition for high-school students taking college courses. Chicago Public Schools, which serves more than 360,000 students, spends about $50,000 per year on the program.

Whether the courses are actually helping Chicago Public School graduates save time on their route towards a college degree remains to be seen.

Whether the courses are actually helping Chicago Public School graduates save time on their route towards a college degree remains to be seen. The city hasn’t actually studied the impact, though Juan Salgado, the chancellor of City Colleges said there are plans for that type of research.

Though its effects haven’t been measured, the city has dramatically expanded the program during outgoing Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s time in office. In 2018, 4,195 students graduated from Chicago public high schools with at least one credit earned through a college course, up from 1,630 students in 2014.

Officials argue that the growth in participation is a sign that access to the courses is becoming more equal. “I think the expansion speaks for itself in the sense of equity,” Emanuel said in a phone interview late last year.

Finding qualified teachers to help student is also a challenge

But even as Chicago has successfully expanded dual-enrollment programs, the city still faces challenges giving all students an equal shot at these opportunities.

In Chicago, like most places that offer college-credit opportunities in high school, students who want to take advantage of the courses need to be “college-ready,” a designation typically determined by a standardized test score, but which can sometimes include other factors. That label can also shut out students who are struggling in school.

“We’re going to have to think about how we expand other early credit opportunities beyond the students who are already college ready,” said Melissa Connelly, whose nonprofit organization, One Goal, works closely with high schools in low-income areas to support students on their path towards a college degree or post-high school credential.

Another hurdle that limits which students get to take these courses: It can be difficult to recruit qualified teachers to under-funded schools.

In many jurisdictions, in order for a high-school teacher to qualify to teach a college course, they need not only a master’s degree, but also a significant amount of master-level course work in the specific topic they’re teaching. For schools with limited budgets to pay teachers and challenging environments — often two features synonymous with schools serving low-income students and students of color — that can be a tough find.

Lucy Hewett

Lucy Hewett

Charles Anderson, the principal of Michele Clark Academic Prep Magnet High School on Chicago’s West side, joked that when he comes across a teacher qualified to teach dual-credit courses, he thinks, ‘Wait, we have to wine and dine this person for a little bit.’

Sitting in a conference room attached to his office with a giant Rubik’s cube and board games, Anderson explained some of the other challenges he’s come up against in his push to offer his students more opportunities to take college-level courses both inside his high school and at the local community college. Roughly 96% of students at his school are black and about 76% are low-income.

“When we looked at our numbers this year we saw that it was probably about 25% fellas,” said Anderson, referring to young men. “How do we get them hooked into it?”

Anderson said he’s hoping to rope more boys into the idea of taking college credits early in their high-school career in part to help convince them that the experience isn’t just a “girl thing.”

In El Paso early colleges, equity is top of mind, but not always easy to achieve

Even in schools designed specifically to leverage early college credit opportunities to close gaps in access to higher education, achieving equity can be a challenge.

In the mid-2000s, with the help of grants and other resources, the city of El Paso, Texas launched its first early college high school, a program that allows students to work towards an associate’s degree while they earn their high-school diploma.

Even when dual-credit programs reach students who can most benefit from the opportunity, it doesn’t necessarily mean they will breeze through college.

As Tonie Badillo, the dean of dual credit and early college high schools at El Paso Community College, remembers it, the whole idea behind an early college high school was to “even the playing field,” for students who are the first in their family to go to college, low-income or may be learning English as a second language.

“They have so many strikes against them to begin with, how can we provide a safe environment, a small school, additional support services to help them succeed?” Badillo said. “I always say, ‘Keep in mind that goal, those are the students we’re serving with the early college.’”

But it hasn’t always been easy to keep that mission front and center as El Paso’s early college movement has grown to include 12 schools with plans for five more in the 2019-2020 academic year. Badillo spoke with MarketWatch after a September meeting with principals and others involved in the region’s early college system. The get-together featured some light grumbling about a recent effort from the Texas Education Agency to ensure that, as Badillo put it, “the right student is receiving support.”

Early college high schools that want to receive the highest designation under “the blueprint,” as the Texas Education Agency effort is known, must recruit and enroll levels of students under-represented in college that meet or exceed the proportion of those students in the district at large. The designation is essentially another feather in the schools’ cap.

“This year, the schools got their report card and they saw where they would be short,” Badillo said in the interview. In the past, several of El Paso’s early college high schools had a rating of distinguished. “But now, with this new metric, none of our schools are distinguished.”

El Paso is about 80% Hispanic, so schools don’t have a problem recruiting students from that group — one of those designated by the blueprint as being under-represented in college — but some do struggle more to attract black and male students, Badillo said.

Rudy Gutierrez

Rudy Gutierrez

At Northwest Early College High School, a collection of portable classrooms surrounded by the local community college, desert, mountains and the interstate, principal Tracy Speaker-Gerstheimer said recruiting enough students of any type to fill the class — let alone more specific under-represented demographics — can be challenging.

The district from which she’s recruiting is relatively small and has only one other traditional high school where, growing up, most students envisioned their high school experience. Convincing them to head to the collection of portables with no band and sports teams can be tough.

Speaker-Gerstheimer, a first-generation college graduate herself, said she believes so much in the early college high school experience that she wants to wear those middle schoolers and their parents down, particularly those families who might not be thinking about college.

“I’ll ask sometimes in my recruitment meetings with parents, ‘Did you open a savings account for your child when they were born? And no one will raise their hand — or maybe one person — and I’ll say, ‘Neither did my parents,’” Speaker-Gerstheimer said.

“I hope that by talking about it, students can see: now there’s a person, their parents weren’t educated, she took out loans and she figured out how to do it and I can do it.”

Taking college classes aren’t a panacea

But even when dual-enrollment programs do reach the students who can most benefit from the opportunity, it doesn’t necessarily mean students will breeze through college.

Orduna’s experience taking college courses in high school allowed him to skip some required introductory classes, like a writing course. It also helped him improve his time management and other skills to get them to the level of what’s required in college.

Still, Orduna — who took chemistry, physics, calculus, an introductory engineering course and ancient Greek history his first semester at UofI — said he wishes he took more college science classes while in high school to help him better prepare.

“It was very heavy,” Orduna said of the transition to UofI. “I underestimated it. It was kind of like a wake up call to get my stuff together.”

(This story was originally published on May 20, 2019.)