(Bloomberg Opinion) — The revelation that, by the age of seven, 53% of British kids will own a mobile phone, will come as good news to one group in particular: advertisers.

By the time U.K. youngsters are 11, the ownership ratio reaches a whopping 90%, according to a report published on Tuesday by the research consultancy Childwise. And as the penetration of smartphone usage rises, it creates more opportunity for advertisers to get in front of young eyeballs. Parents need to get clued up if they want to stop that from happening.

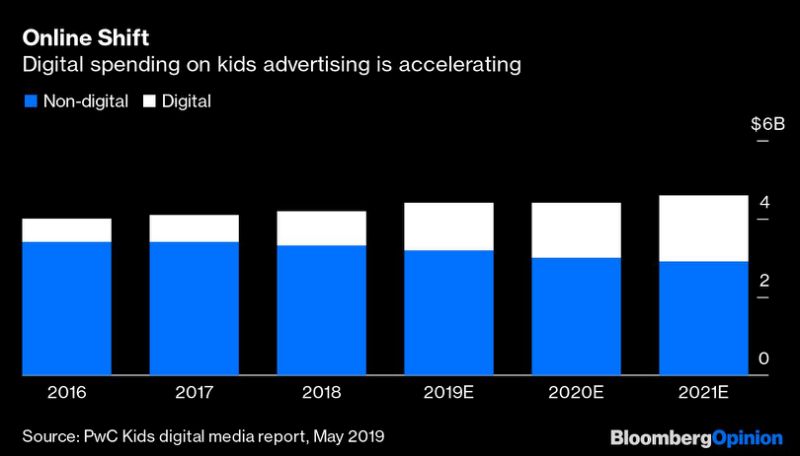

For now, advertising targeted at children has been slower to migrate online than in the broader industry. Whereas more than half of the world’s $614 billion of ad spending is now online, less than a third of the outlay for ads targeting children is digital, according to a 2019 study by PricewaterhouseCoopers.

That’s partly because of concern from advertisers about the nature of online content: Nestle SA doesn’t want its chocolate bars advertised alongside inappropriate videos, for instance. But regulators have also been remarkably proactive in ensuring the necessary protections are in place for youngsters. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation makes it illegal to process the personal data of children under the age of 13, as does the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act in the U.S. Similar rules are in the works in China and India.

Theoretically, that keeps the big advertisers from serving children with digital ads catered specifically to their individual sets of interests. While it’s possible to strategically target online ads to a precise subset of 18- to 35-year-old males — say those with a household income of $100,000 to $150,000 who are interested in video games and soccer — the same is not true for kids.

However, that only holds up if parents are ensuring their offspring access the web through the appropriate portals. Tech giants like Apple Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google have come a long way in giving parents the tools they need to monitor and control their little cherubs’ internet access (even if savvy kids have found ways to circumvent them). Under pressure from investors, Apple introduced the “Screen Time for Parents” function to the iPhone in 2018, which lets parents see which apps their sprogs are using and sets daily time limits for both the phone and individual apps. Google has similar functions in Android.

Google’s YouTube is hugely popular among kids. If they use the video platform’s normal website, then they risk being exposed to inappropriate content. But if they use the YouTube Kids app, there are checks in place to prevent that happening. Brands can still pay to have their ads placed alongside particular content — they just won’t know as much about the individual interests of the person watching the video. That’s really no different from classic television advertising. In fact data from Ofcom, the British regulator, suggests that children don’t spend significantly more time in front a screen now than they did 10 years ago. In 2010 children aged eight to 11 spent 32.5 hours a week online, gaming or watching TV. In 2018 that had risen to just 33.5 hours. They just spend more time online than they do in front of the tube.

One caveat, of course, is that if you’ve tied control of the YouTube Kids app to your own Google account, then there’s a chance you’re letting Google know you live in a household with a youngster (if it didn’t already know, that is), so you might get yourself served with ads aimed at parents. (There’s other issues such as kids lying about their age, or simply using their parents’ apps at will, but I digress.)

The pace at which children are getting their own smartphones means that the digital growth in advertising spend targeted at teens, preteens and younger is outpacing that for other ads. It’ll grow 22% over the next two years, PwC estimates, outstripping the 13% growth that the World Advertising Research Council forecasts for online ads as a whole. If parents want to prevent their offspring from being bombarded with ads, they have many of the tools to do it.

As ever with all things digital, it may be that older generations require more education than their progeny.

To contact the author of this story: Alex Webb at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at [email protected]

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe’s technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion” data-reactid=”36″>For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

<p class="canvas-atom canvas-text Mb(1.0em) Mb(0)–sm Mt(0.8em)–sm" type="text" content="Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.” data-reactid=”37″>Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.