An illustration of a Covid-19 vaccine and earth globe.

Joel Saget/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Blame — or thank — central banks.

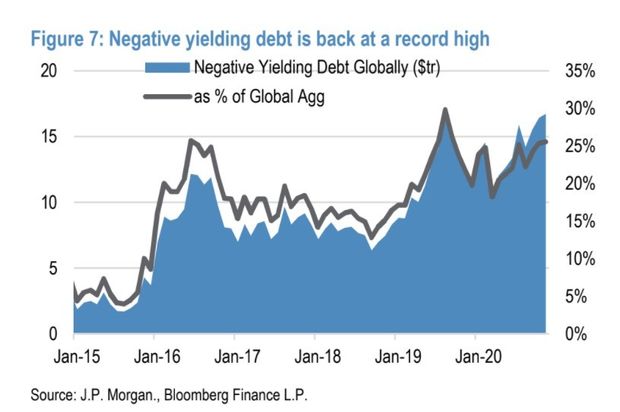

The pile of global debt now trading at negative yields has returned to record territory at about $17 trillion, after briefly dipping to nearly $10 trillion earlier this year, according to J.P. Morgan.

The culprit? The staggering $17.1 trillion collective balance sheets of four key central banks. The combined balance sheets of the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan and the Bank of England by $5.2 trillion over the past 12 months, mostly in a bid to offset the economic carnage caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

Central banks have greatly expanded their balance sheets this year by ramping up asset purchases and by extending emergency funding programs that help keep credit flowing during the crisis.

While those efforts have been viewed as widely successfully in terms of keeping borrowing costs low, the intervention in markets also has been blamed for pushing investors further into riskier assets that yield far less than in the past.

“That in turn led to a tremendous amount of negative yielding debt globally,” a team of J.P. Morgan credit analysts led by Eric Beinstein wrote in their annual credit outlook, a situation they view as “putting further pressure on investors to find yield wherever possible.”

The yield on the U.S. 10-year Treasury note TMUBMUSD10Y, 0.845% fell 3.6 basis points Friday to 0.842%, as Germany and France extended lockdowns to contain the pandemic, leaving the U.S. benchmark rate almost 1.1 percentage points lower the year to date, according to FactSet data.

Meanwhile, U.S. stocks finished in record territory on Black Friday, with the S&P 500 index SPX, +0.24% and Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, +0.92% ending at new all-time highs in an abbreviated holiday session, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +0.12% closed 0.1% higher, just under its 30,000 milestone set earlier in the week.

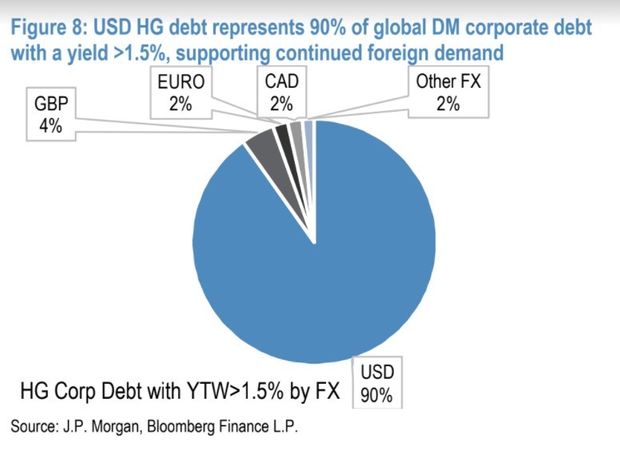

But for fixed-income investors, the prospects of lackluster returns likely mean the biggest part of the $10.5 trillion U.S. investment-grade corporate bond market will be the “only game in town” next year for investors looking for yields greater than 1.5%, the J.P. Morgan team wrote.

Here’s their chart tracking negative yielding debt globally since 2015, including as a percentage of the global aggregate.

Record negative yields globally

J.P. Morgan research

The team also looked at yields on global investment-grade corporate debt, after factoring in hedging costs that “have fallen substantially in 2020,” as a result of the “uniformity of monetary policy globally.”

They found that $5.7 trillion, or about 90% of all U.S. investment-grade corporate debt, fits their yield target of greater than 1.5%.

Yields greater than 1.5%

J.P. Morgan

U.S. corporations borrowed at a record pace in 2020, bringing their debt loads near to all-time highs even as earnings slumped, and while paying investors some of the skimpiest returns ever.

Read: A binge? Bulge? Or just the new normal for debt in America as Fed helps spur string of records

Despite the prospects of low returns, Beinstein’s team at J.P. Morgan also note that corporate credit metrics are “weak and unlikely to improve significantly in 2021,” as companies try to maintain earnings growth while hoping for a light at the end of the tunnel of the unrelenting pandemic after several promising COVID-19 vaccine candidates emerged.

The corporate debt sector also will try to look past U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin’s decision to abruptly end several key emergency Fed lending programs, including two corporate credit facilities that have served as a backstop for the market in case of future turmoil.

“The Federal Reserve has utilized less than 10% of its credit programs, so they served more value from a ‘signaling’ perspective than from actual purchases,” said Scott Ruesterholz, portfolio manager at Insight Investment.

“As President-elect Joe Biden’s Treasury Secretary could reverse this decision in 2021 and reopen these facilities, the market has been able to look through this temporary disruption.”

J.P. Morgan’s team also expects a far less blistering pace of U.S. investment-grade corporate bond issuance in the year ahead after an “outlier year in 2020,” as corporations amassed a war chest of cash to help serve as a bridge during the crisis.

J.P. Morgan’s forecast is for net growth of only 6% for the U.S. investment-grade corporate bond market in 2021, or half of this year’s growth rate.

In other words, even if investors aren’t in love with the idea of earning yields a bit over 1.5% next year, they probably will still face healthy demand for the new corporate bonds that are issued.

Also read: Here are four reasons why investors might snap up negative-yielding bonds