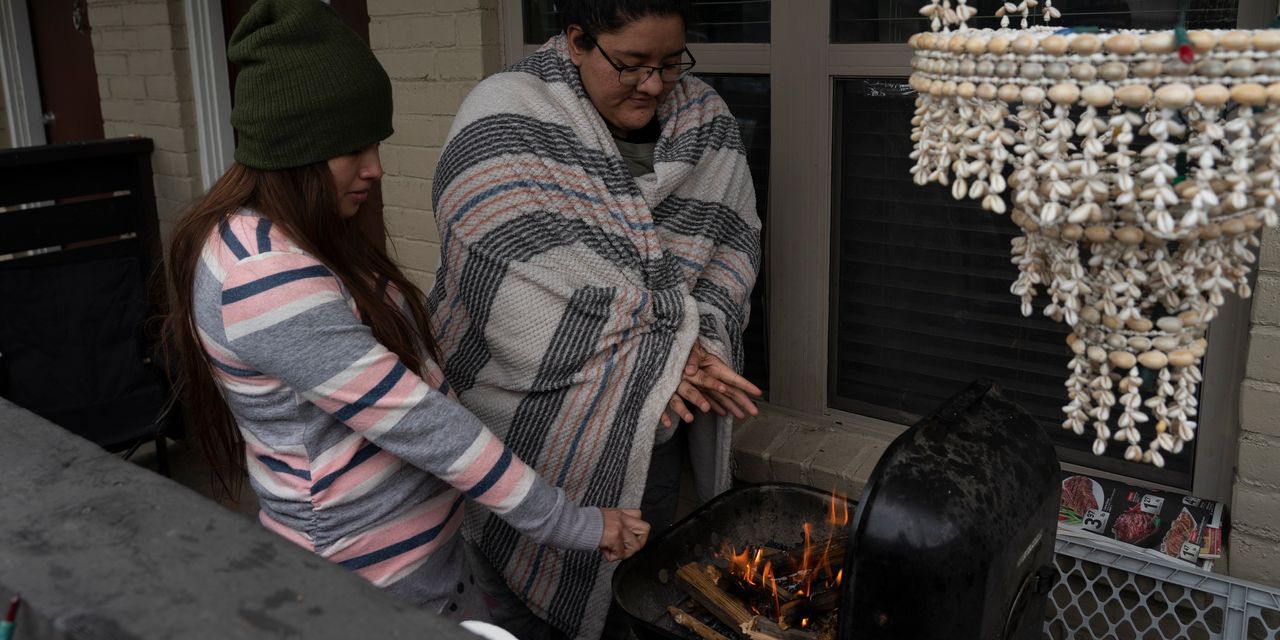

The word “reliability” is often used in the context of the electric grid, and this week’s localized blackouts in much of Texas caused by the deep freezing weather have provoked many related questions.

But too often, the word reliability is thrown around much too loosely in the context of energy. To a lobbyist advocating for the fossil fuel narrative, reliability means one thing. To a lobbyist advocating for the renewable energy narrative, it means another. To operators responsible for maintaining the day-to-day technical operation of the electric grid, reliability has additional meaning that few people contemplate except during extreme weather events such as this week.

Very rarely does a person describe reliability in the context of both “fossil” and “renewable” energy narratives, but I will do that here in the context of searching for solutions to make the electricity grid managed by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, and thus most of Texas, more resilient to extreme weather.

Read: What’s behind the Texas power outages?

While there are many avenues to search, here I point out three areas: the technology level of weatherizing power plants and linkages to policy and market design; natural gas supply; and ERCOT integration with the Eastern or Western interconnections.

Weatherization

The events of the past few days have indicated that multiple types of power generation became inoperable due to cold weather conditions, causing ice accumulation on components and instrumentation failure. Yes, some wind turbines froze up (but not all 10,000-plus of them), some natural gas plants became inoperable (but not all of them), and one nuclear reactor shut down (but not the other three).

Each electricity generation technology has its pros and cons. We should resist the narratives that focus blame one technology or another because it detracts from making the entire system reliable in the face of all circumstances.

We’ll learn more details about this week’s events over time, but we can ask a reasonable question: Could power plant operators have made investments to maintain the ability to operate in icy and freezing temperatures? This was recommended after a similar situation in 2011. Then why weren’t weatherization investments made?

The answer to this second question usually comes down to a cost-benefit analysis of engineering enhancements: How much does it cost for what benefit?

Imagine going to power plant owners and state regulators and telling them we need to ensure that all Texas power plants can operate at full capacity in the case of four straight days of subfreezing temperatures with snow and freezing rain. You might have received the same response as if postulating the extreme rain event that was Hurricane Harvey. The answer would have likely been: “That event has never occurred. Why prepare for an event that hasn’t ever happened and might never happen?” or “We have an electricity market for that.”

Markets are good at incentivizing an average low cost for wholesale electricity. They are not as good at protecting public health and safety during outlier events.

The investments for increased electric grid resilience to extreme cold and floods likely lie in the domain of regulation and information disclosure. At the power plant technology level, we need to learn what winterizing preparations were performed, what did and didn’t work, and what Texas can learn from power plant owners in more northern climates.

Natural gas supply

Just as in 2011, the natural gas storage and delivery system could not deliver enough natural gas to power plants to meet all heating demands. The electricity grid and natural gas pipeline network are interdependent: Natural gas power plants require gas deliveries to generate electricity, and natural gas pipelines require electricity to pump gas.

While this is a complicated problem to solve, it is not impossible. The state of Texas can fund studies to understand these gas and electricity interdependencies such that for given weather scenarios, heating types, and power-plant generation fleets, we have readily available estimates of Texas’ peak heating and electricity supply.

ERCOT integration

Finally, why?

This is the question that everyone outside of Texas asks when they learn that ERCOT, which covers 85% of Texas electricity, is not fully connected with either the Western or Eastern grids, the two larger North American grids.

Depending on your narrative, you can start with remembering the Alamo to ending up with Texan independence from federal regulation by avoiding interstate commerce of electricity. But at a time like this, the present matters more than the past.

While ERCOT is connected to the other grids via a small amount direct current (DC) ties, we should promote solid debate on the pros and cons of increased integration of the ERCOT grid with the rest of the country. On the con side, ERCOT is big enough to enact many policies and investments wholly within ERCOT, such as transmission lines, that don’t cross state boundaries and so wouldn’t require agreement from other state legislative and regulatory bodies. On the pro side, smaller grids have less buffer to handle events such as this week’s cold-induced power outage in ERCOT.

This grid integration decision is not one to make in one month or one year, but one that can be contemplated over several years. The best solutions are not obvious, and the answers will not be for today’s grid, but for the grid in 20 years or more.

The solutions hinge on the ability to handle extreme events. There might be increased, but still loose connections to the other grids.

For example, we might consider ERCOT as a “microgrid” among the others, just as the University of Texas at Austin’s campus is a micro grid within the city of Austin. Our campus is synchronized and connected with the larger grid, but there is usually no power flow across the “border” between campus and Austin. The connection and synchronization exist in case of emergency situations when power flow, one way or the other, helps maintain services.

Another option might be for ERCOT to increase its DC tie capacity.

As we emerge from the cold this week, we should avoid using oversimplified narratives of how one technology failed over another. The grid is more resilient because we have multiple types of power generation. We can seek increased resilience not only via new types of technologies, but also via new means of energy system cooperation.

Now read: Texas’s ongoing power disaster may be strongest case yet for renewable energy

Also: Texas mayor says local government ‘owes you nothing’ as residents go days without heat or power

Carey W. King is a research scientist and assistant director at the Energy Institute, University of Texas at Austin and the author of “The Economic Superorganism: Beyond the Competing Narratives on Energy, Growth, and Policy.” Follow him on Twitter @CareyWKing.