You read about the “retirement crisis” in newspapers and on the internet. You see members of Congress pushing to expand Social Security and bail out insolvent “multiemployer” pensions, all in fear of retirees falling into poverty.

In a country of 325 million people, it’s certainly not hard for reporters to find legitimately heart-rending stories of Americans who, for one reason or another, reached retirement age with inadequate savings.

But an accurate picture depends on data, not anecdotes. And for readers weaned on headlines such as “A Generation of Americans Is Entering Old Age the Least Prepared in Decades,” the data on retirement are stunningly positive.

The things that should be going up are going up, including the share of Americans with retirement plans, the size of our retirement-plan contributions, total retirement savings, retirees’ incomes, and retirees’ satisfaction with their financial security. And the things that should be going down — like poverty in old age and dependence on Social Security benefits — are going down.

Counterpoint: The biggest bull market ever — yet disaster looms for retirees

Today’s retirees are doing well

Data from the Congressional Budget Office show that from 1979 to 2016, average incomes for working-age households rose 64% above inflation. Over that same period, average household incomes for retirees grew 104% above inflation.

Put another way, in 1979 the average retiree household’s income was equal to 73% of working-age households’ incomes. By 2016, retiree incomes were equal to 91% of working-age households’ incomes, despite retirees facing a lower cost of living, being more likely to have paid off their mortgages, and having smaller households to support.

Rising private retirement plan benefits are a part of this: the CBO data show that from 1980 to 2016, Social Security benefits received by middle-income retiree households increased by about 50% above inflation, but their private retirement-plan benefits rose by over 150%. This is a failing retirement system?

Likewise, Census Bureau research using IRS data shows that the share of retirees with incomes below the poverty threshold plummeted from 9.1% in 1990 to just 6.9% in 2012. Yet somehow, amid hundreds of articles on the retirement crisis, these data are overlooked.

But retirees realize all of this, even if politicians and the media aren’t listening.

Nearly eight in 10 retirees tell Gallup they have “enough money to live comfortably,” versus only six in 10 working-age households. In the Federal Reserve’s 2018 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking, only 4% of current retirees said they were “finding it hard to get by.”

In the federally funded Health and Retirement Study, 81% of retirees in 2016 described their retirement as either as good or better than their preretirement years, up from only 65% in 1992. In that same 2016 survey, 93% of seniors described their retirement as “very” or “moderately” satisfying, versus only 77% in 1992.

Likewise, the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances finds that 75% of Americans age 65 or more in 2016 reported having enough income to at least maintain their preretirement standard of living, versus only 61% of retirees in 1992.

Sure, Americans worry. For instance, in a 2017 Vanguard survey, 54% percent of retirees feared that America faced a “retirement crisis.” But only 4% of retirees in Vanguard’s survey described their own financial situation as a “crisis.” Similarly, other surveys like Gallup and the Health and Retirement Study show that working-age households in past years were worried about retirement. But now that those households have retired, the vast majority feel financially secure.

Read: 401(k) balances increased very little in the last 10 years

Why retirement finances won’t get worse

Begrudgingly, the retirement crisis crowd will admit, maybe things aren’t so bad today. But what about the future? What will happen to retirees as traditional defined benefit pensions give way to 401(k)s?

The answer is that retirement incomes will probably go up. Assets in private-sector defined-benefit pensions, the kind that pay a set amount each month, were typically worth about 16% of gross domestic product. Today, 401(k)s and IRAs, which took defined-benefit plans’ place, have assets worth 76% of GDP.

But what about all those pessimistic studies the news media loves to cite? Many have flaws, both in terms of how they project future retirement incomes and how they judge how much income retirees will need. For instance, a 2019 Government Accountability Office study claims that “about half of households age 55 and older have no retirement savings.” But the GAO counts those who have a traditional pension and no 401(k) or IRA accounts as having no retirement savings. That’s nuts given that 45% of Americans 55 and older are still owed pension benefits.

Likewise, a recent World Economic Forum report generated headlines world-wide by claiming that the average retiree would run out of money after only about 10 years. But this figure assumed retirees received no Social Security benefits; include Social Security and the average U.S. retiree’s savings would last more than 30 years.

A third study, from the National Institute for Retirement Security, claims a $14 trillion “retirement savings gap,” but assumes that every penny of the multi-trillion dollar deficits in state and local government pensions is solved by cutting benefits. In reality, the vast majority of those benefits will be paid.

For myself, I’ll rely on the best retirement model in the business, which belongs to the Social Security Administration and has been improved and double-checked for over two decades. The SSA model finds that the median household born in the Great Depression retired with a total retirement income equal to 109% of their inflation-adjusted career-average earnings, far above the 70% replacement rate financial advisers recommend. Now fast forward to Gen X, who we are led to believe face a retirement crisis. For Gen-Xers, SSA projects a median replacement rate of 110% of career-average earnings.

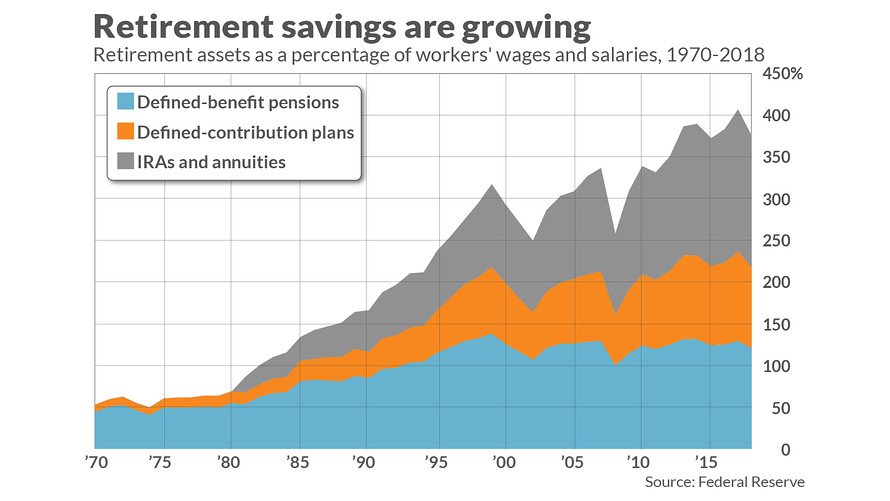

Why won’t there be a crisis? One reason is that retirement savings have gone through the roof. Back in 1973, when participation in private-sector defined-benefit pensions peaked at just 39% of the workforce, total retirement plan assets were equal to 55% of total employee wages and salaries.

Today, with 61% of private-sector workers participating in a retirement plan, total retirement savings have increased nearly sevenfold to 375% of employee wages. And recent Federal Reserve research finds that the distribution of retirement savings hasn’t significantly shifted as defined-benefit pensions gave way to 401(k)s.

Are there problems? Sure. And slowly but surely they’re being addressed, at least in the private sector. But the narrative on retirement savings is so skewed toward an apocalyptic vision of a “retirement crisis” that step one is simply getting a grasp on reality.

Andrew G. Biggs is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and former principal deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration during the George W. Bush administration. Follow him on Twitter @biggsag.