Every parent knows that kids cost a lot of money, for everything from food, clothing and shelter to child care, education and health care. They’re right: studies show that a two-parent family with two kids devotes between 31% and 47% of total household spending to its children. And at the same time that parents are raising their children, they’re supposed to be saving for their own retirements.

Some good news for parents: While child-raising costs and retirement savings are rarely mentioned together, having kids might mean you actually need to save less for retirement than your childless friends.

People saving for retirement usually aim to maintain their preretirement standard of living once they stop working. For a childless household, that’s pretty straightforward. Financial planners often say that a retirement income equal to of 70% of preretirement earnings is enough, since many expenses — such as work-related costs, taxes and the need to save for retirement — are lower or even disappear in retirement.

But what about parents with kids? Parents might be able to get away with saving less than nonparents simply because they have a lower preretirement standard of living, given how much of their salaries was spent on their children rather than on themselves. As one economist joked, parents get used to eating peanut butter while nonparents with the same incomes feast on caviar and fine wine.

A word of caution: If parents increase their spending on themselves once their kids leave the nest, they’ll need just as much retirement savings as nonparents.

My own research suggests that spending by households with children drops significantly as kids become economically independent. Spending by childless households, by contrast, continues to increase up until the time they retire.

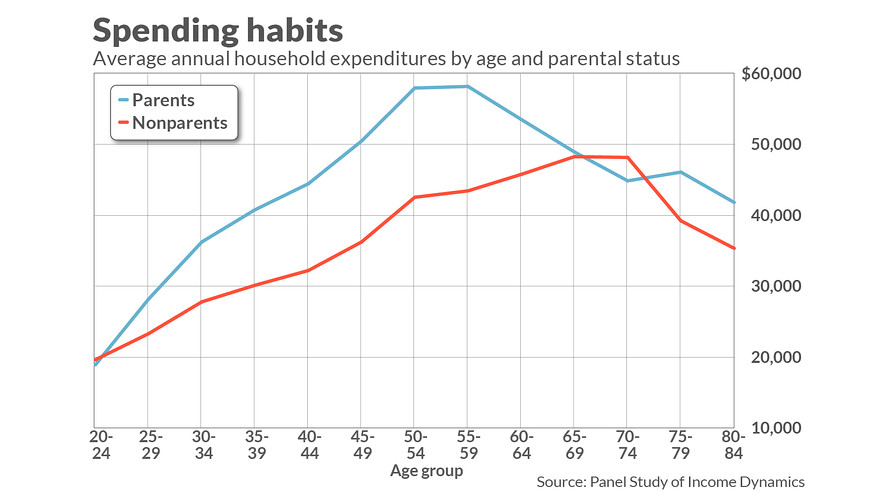

In a new American Enterprise Institute working paper, I use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics to show how spending by parents and nonparents changes over the periods in which children entered the household, grow to adulthood and then become financially independent. As this chart shows, the patterns of household expenditures are distinct.

At nearly every age, nonparents spend less than parents. But that’s not surprising since most parental households have two adults while most nonparental households have only one. What is surprising is that the patterns of spending over time are so different.

For nonparents, household spending rises steadily from their 20s through retirement age, after which spending declines. But for parents, spending rises faster during the years in which kids are likely to come on the scene, but then declines in the years children are likely to leave home. By ages 65 to 69, total household spending by parents is 16% lower than when parents were 50 to 54 years old. For nonparents, total spending rises 13% between these two periods. The decline in spending by parents as they approach retirement is largely in education, housing and transportation costs, all of which are associated with raising children.

What does this mean for retirement planning? The short story is that parents’ spending in retirement is lower relative to their preretirement earnings than it is for nonparents. For instance, spending by parents aged 65 to 69 is equal to 80% of their earnings from ages 45 to 49, while nonparents spend an amount equal to 94% of their ages 45 to 49 earnings. To afford that higher level of spending in retirement, nonparents need to save a bigger share of their preretirement earnings.

These results could also mean that some studies are overstating the retirement savings gap by failing to account for the costs of raising children. A 2014 study by Alicia Munnell and her co-authors concluded that if we adjusted retirement savings targets to account for the share of parents’ earnings that were spent on their kids, it could dramatically reduce the share of households found to be undersaving, from about 35% to around 23%.

In a 2009 study, I found that adjusting retirement income targets for preretirement spending on children would increase the typical household’s retirement income replacement rate by about 17 percentage points, from around 75% of preretirement earnings to about 92%. But most studies that predict a retirement crisis of inadequate saving fail to account for how children affect their parents’ need to save for retirement. As a result, we may be overestimating the challenges Americans face in saving for retirement.

When different studies find conflicting results, more research is needed. But if you’re a parent planning for retirement, it makes sense to look at how much you’re currently spending on yourself and your partner. That’s a decent basis to estimate what kind of income you’ll need in retirement.

Understanding that it’s your own preretirement standard of living you need to maintain in retirement, not that of your children, might make saving for retirement seem more achievable.

Andrew G. Biggs is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and former principal deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration during the George W. Bush administration. Follow him on Twitter @biggsag.

More from Andrew G. Biggs: Fears of a retirement crisis are overblown — and these numbers prove it