As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing this month, much of our attention will be on the “what” and the “who” — the technology that took us there and the heroic teams of astronauts and engineers who did it. But missing from the picture will likely be an important “how”: the free market and research science at work in Project Apollo.

NASA didn’t achieve Apollo on its own. American business and science helped — on contract.

There’s probably nothing more routine, and important, in the American experience as the contract. It’s a mainstay of commerce, and of government-industry-science collaboration. A simple piece of paper, it defined a reachable project goal, a technological endpoint. It set the terms, made a promise, and sealed a bond. As the U.S. charts its spaceflight future, we ought to remember the lessons of the contract in the Apollo business model.

Only three years young when President Kennedy announced the moon goal in May of 1961, NASA was made up of engineers and managers from America’s earlier aeronautical agencies and the military services. They had their own research centers and labs. But they could not develop all of the processes and architectures, or the actual machinery, of moon-flight.

NASA had no choice but to inherit and adapt the “contract system” from the defense establishment, the one that protected the U.S. and its allies from Soviet Russian and Communist Chinese aggressions through the 1950s. In a golden age, from the Manhattan Project to Project Apollo, the government sponsored private industry and academic research to get things done. These were the institutions with the track records of designing and building military aircraft and missiles — an arsenal of democracy for the Cold War and Space Race.

So NASA contracted out the different parts of Project Apollo to American industries and universities for the actual rocket boosters, or spacecraft, or computers and instrumentation, or space suits and biomedicine. NASA bought engines, and it bought Tang.

At its peak year of funding in 1966, NASA received a record 4.41% of the federal budget (it only receives 0.49% now). Besides paying for its own 36,000 civil-service employees and centers, most of this money went to 250 major contractors and subcontractors, who employed over 360,000 engineers, scientists, and workers across the country.

Some contracts were large. North American Aviation of California (now part of Boeing BA, +0.32% ) received $6 billion to build the Command and Service Modules and parts of the Saturn booster. Charles Draper’s Instrumentation Laboratory at MIT leveraged its contracts to transform into a multimillion-dollar not-for-profit research entity known as The Charles Stark Draper Laboratory.

Others contracts were relatively small. General Motors’ GM, +0.18% Allison Division in Indiana earned a modest $5 million to make the lightweight tank of the Lunar Module descent stage. NASA expanded Maurice Zucrow’s Propulsion Lab at Purdue University, which otherwise thrived on much smaller research and education contracts, in the tens of thousands of dollars.

But the system worked: Apollo came in on time, within Kennedy’s 10 years; and on budget, at about $20 billion (in 1960s dollars).

Read: Myths and facts about the 1969 moon landing

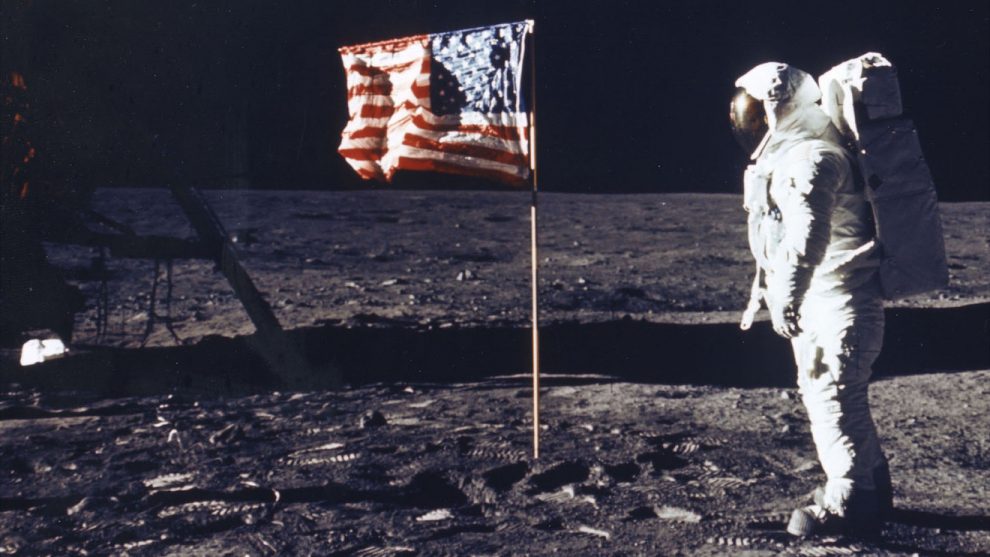

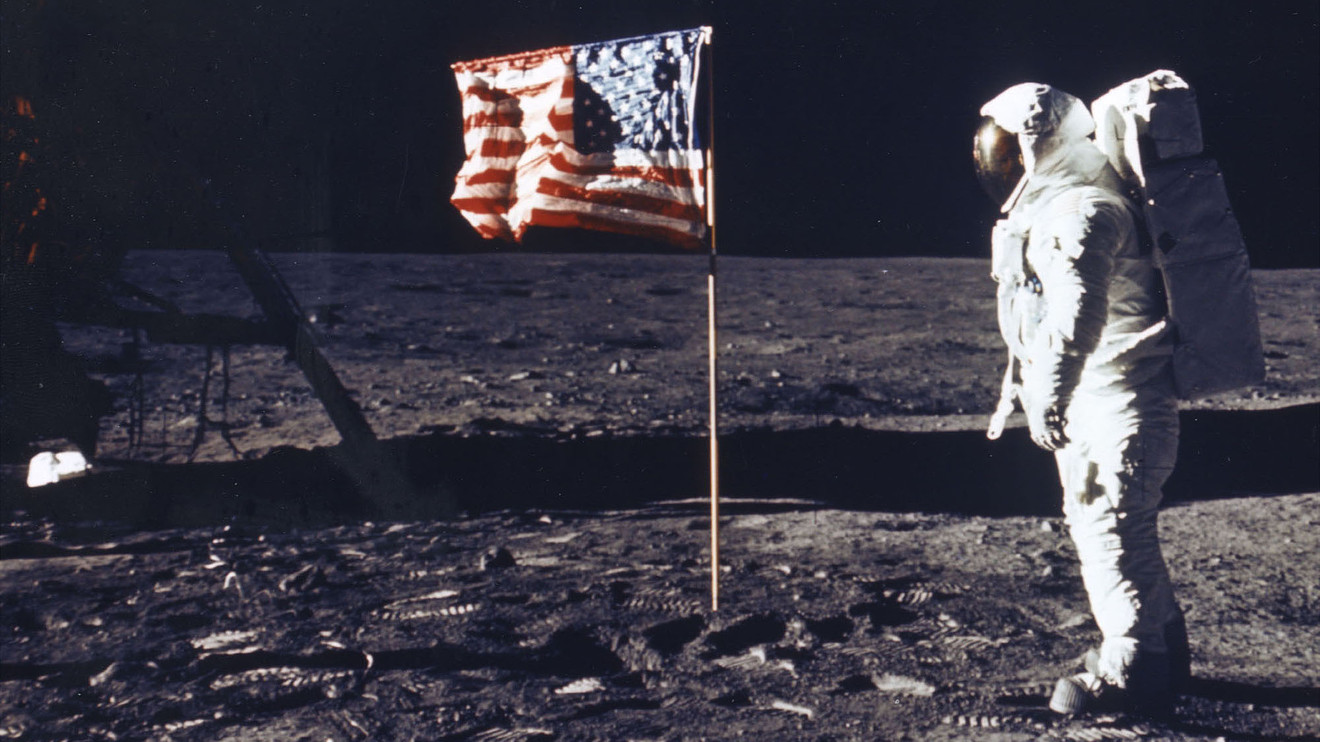

Apollo was a proven combination of inheritance and improvisation. Neil Armstrong summarized it perfectly in his famous words on July 21, 1969, when he first stepped onto the moon: “that’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Here were terms that he had read, time and again, in the trade and professional magazines of aviation and aerospace, of missiles and rockets. He was just making personal what was already professional.

“Small step” was a common metaphor for the painstaking work of conservative engineering, like adapting the Saturn rocket engines, and lunar guidance and control systems, from existing ones, and testing and retesting then on Apollo’s terms.

“Giant leap” had always meant reaching for new speed and altitude records. We had done this before: like the Atlas ICBM to cross continents, and that also propelled Project Mercury to earth orbit; or the X-15 test plane, the history’s highest and fastest (Armstrong flew it). Now “leap” meant creating lunar orbit rendezvous and the innovative Apollo spacecraft to match.

“Moonshots” are not easy, or all that sustainable. The moment has to be just right. It has to marry drive and money, state and market, project endpoint and contract. Public support counts too. Opinion polls consistently hovered at below 50% in support for the moon landings. The country also reached a point of disinterest and exhaustion by 1970, what with a sagging economy and social protests at home and the war in Vietnam. President Richard Nixon canceled the last few Apollo missions, and plans for a lunar colony, as NASA moved on to new contracts for the Space Shuttle.

Like any human endeavor, the aerospace contract system has had its corruptions, often summarized as part of a “military-industrial complex,” one that’s rewarded crony capitalism, overpayments, mismanagement, and conflicts of interest. Nor have the politics always been pretty, beset by partisan disputes and pork-barrel allocations.

For all of their fanfare, the new commercial space entrepreneurs like Elon Musk’s Space X are following the same government-industry-science contract model, though with more freedom of action than ever before. That’s the model that has worked, with all its successes and failures. So long as we set an achievable goal, and a fair set of government contracts and profit ventures, to the best companies and laboratories.

When we return to the moon or head on to Mars, it will be thanks to our pragmatism and business sense — the many small steps of good old American know-how.

Now read: 5 innovations the Apollo moon program brought that changed our life on Earth

Michael G. Smith is a history professor at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., who specializes in the Space Race and Cold War.