Wall Street and the news media have paid considerable attention to U.S. home mortgage modifications, but not much notice has been given to the growing problem of re-defaults on these modifications. Re-defaults are a massive problem — and endanger the U.S. mortgage and housing markets.

What is a mortgage modification? In the midst of the housing collapse more than a decade ago, mortgage modifications were rolled out to enable millions of delinquent homeowners to avoid having their home foreclosed. In its latest report, the non-profit Hope Now consortium — the major source for modification data — estimated that 8.7 million permanent mortgage modifications have been implemented in the U.S. since the end of 2007.

A modification created permanent changes to the original mortgage by one or more of the following: (a) stretching out the amortization period; (b) reducing the interest rate; (c) adding the delinquent interest arrears to the outstanding principal (known as capitalization), or (d) reducing the amount of the principal owed.

The 8.7 million permanent modifications do not include the temporary fixes that lenders have provided. According to Hope Now, roughly 17 million temporary solutions have been rolled out under what’s called “Other Workout Plans.” The two most important ones are called forbearances and repayment plans. Under these plans, millions of delinquent borrowers were provided a temporary deferment or reduction of the payments due until their financial condition improved. These temporary solutions are not reported under permanent modifications. Nevertheless, owners given temporary workout solutions are considered current on the mortgage.

Re-default mess

The U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) regulates national banks and publishes a quarterly Mortgage Metrics Report. The OCC data comes from banks, which are the largest servicers of residential mortgages. In its report for the first quarter of 2013, the OCC stated that these servicers had modified slightly more than 3 million loans between the beginning of 2008 and the end of 2012. Of these modified mortgages, 47.3% of them were still current at the end of the first quarter of 2013. The rest were either seriously delinquent, in the beginning of foreclosure proceedings, had already been foreclosed, or were no longer in the portfolio of the servicer.

In its most recent report for the first quarter of 2019, the OCC noted that 21% of the most recently modified loans had re-defaulted within six months.

More than 3 million loans guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) that were in Ginnie Mae pools had been modified between 2008 and 2013. A 2014 report found that they had performed badly. Roughly 57% of these modified loans had re-defaulted by 2013.

In July 2016, Fannie Mae released a dataset of close to 700,000 loans modified between the beginning of 2010 and the end of 2015 to provide greater transparency of modification performance. In February 2017, Fitch Ratings published a report based on Fannie Mae’s dataset entitled “Risk Growing in Mortgage Loan Modifications.” The authors asserted that it was reasonable to assume the trends they found for Fannie Mae modified loans would also apply to loans modified by others.

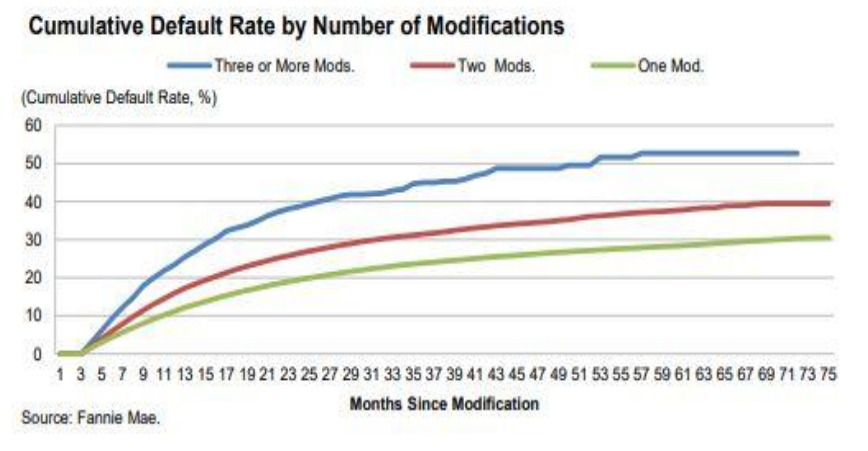

The Fitch report emphasized that the most recent Fannie Mae modifications in 2015 showed the fastest re-default rates since 2010. The analysis showed this was due to the steadily rising percentage of modifications between 2010 and 2015, which were second- or third modifications. In 2011, 95% of all the modifications originated were first modifications. By comparison, more than one-third of the modifications in 2015 were second- or third modifications.

This graph in the Fitch report shows clearly that re-default rates climb as delinquent borrowers enter second- or third modifications:

This deteriorating situation with Fannie Mae re-defaults has been confirmed in the Federal Housing Finance Administration’s (FHFA) latest Foreclosure Prevention Report. It revealed that in the fourth quarter of 2017, 54% of the loans modified 12 months earlier were current and performing.

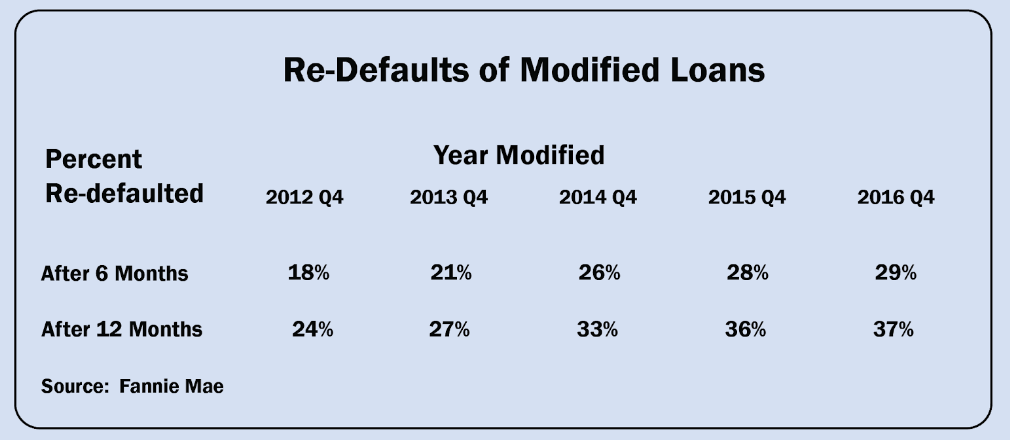

Until 2018, Fannie Mae published re-default rates for its modified loans in its quarterly Credit Supplement report. The table below shows the consistent rise in these rates:

In early 2018, these re-default statistics disappeared from Fannie Mae’s Credit Supplement, which was renamed Financial Supplement. Fannie Mae did report in its annual 10-K Report for 2018 that the 12 month re-default rate had climbed to 39%. Based on Fitch Ratings data, the re-default rate for Fannie Mae loans modified three or more years ago could be approaching 50%.

What about the too-big-to-fail banks? JPMorgan Chase JPM, -2.01% holds the second-largest residential mortgage portfolio in the nation. In its earnings report for the second quarter of 2019, the banking giant showed nearly $10 billion of modified loans (known as troubled debt restructurings). Of these, 43% were listed as having re-defaulted. Bank of America BAC, -2.11% has stated that 41% of its modified loans had re-defaulted.

Re-default rates for the worst of the non-agency bubble era loans

As I explained in a recent column, the worst of the bubble-era loans are found in non-agency securitized tranches. According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), roughly $819 billion of these bubble-era loans are still outstanding. A BlackBox Logic study published in June 2016 analyzed nearly 200,000 subprime loans which had been modified as late as 2013. It reported that 44% of these loans had defaulted within a year and 60% within two years.

For many years, TCW has been publishing a monthly Mortgage Market Monitor using data from CoreLogic’s Loan Performance database. The September 2018 report reveals that prime, ALT-A and subprime securitized mortgages were delinquent for more than two years before the major servicers modified the loan. The majority of these modifications tacked delinquent interest onto the loan’s outstanding principal.

Forbearances and repayment plans

The 17 million “Other Workout Plans” from Hope Now’s latest report included 10.4 million “Repayment Plans” offered to borrowers who claimed unforeseen but temporary financial distress. They were nearly always coupled with a temporary forbearance by which the lender agreed to a three- to 12-month reduction or even suspension of the regular mortgage payment. At the end of the forbearance period, the borrower was then obligated to resume paying the regular mortgage amount plus the missed payments including principal, interest, taxes, and insurance. These additional arrears were apportioned over an agreed upon schedule until fully repaid.

It should be evident that the mortgage modification re-default problem is enormous. Mortgage servicers have been able to avoid foreclosing on many of these long-term repeat defaulters for years. New defaults are occurring regularly. Whether or not this disaster-in-the-making can be resolved will affect millions of U.S. homeowners and the value of their property.

It is important to understand what the OCC’s Mortgage Metrics Report reveals — that for the past five years (or longer), roughly 75%-95% of all mortgage modifications have included capitalization of interest arrears, meaning all delinquent interest payments have been added to the outstanding principal.

Here’s a real example of a 2008 California mortgage that was modified in 2015. The original loan was $400,000. The borrower had been delinquent for several years. The interest arrears combined with the other expenses incurred by the lender to protect its interest in the note amounted to $127,766. This was tacked on to the outstanding principal and the new amount owed on the modified loan came to $515,000. Because the term of the new loan was stretched out to 40 years, the new monthly payment of $2,879 was slightly less than the original payment.

Since the original loan was taken out in 2008, the borrower would have been paying his mortgage for a total of 47 years when it finally matured in 2055. Do you really expect this loan will ever be paid off? The original 2008 mortgage was taken out shortly after the peak in California home prices. The value of the house dropped substantially from then until prices bottomed in 2012. In 2015, the property was almost certainly still underwater, yet this borrower owed $115,000 more than he did seven years earlier. What incentive does a homeowner have to continue paying the mortgage?

Re-default rates could tell us where housing and mortgage markets are headed

Mortgage servicers have instituted close to 9 million permanent modifications to help delinquent homeowners avoid foreclosure and remain in their homes. Critics of these modification programs have argued that they merely kick the can down the road without solving the delinquency problem.

Millions of U.S. homeowners have re-defaulted on their mortgage modification. Even worse, a steadily growing percentage of them have re-defaulted more than once. As home prices continue to weaken, many of these re-defaulters will see that continuing to pay their modified mortgage does not make much sense. I strongly suspect that within a year, both lenders and servicers will face hard choices about these re-defaulters.

Keith Jurow is a real estate analyst who covers the U.S. bubble-era lending debacle and its aftermath. Contact him at www.keithjurow.com.

Read: Here’s the real reason why U.S. home prices haven’t been demolished

More: These are the least tax-friendly states in America